Pandora, a Keen-Eyed Satellite Built to Study Exoplanets, Is Ready for Launch

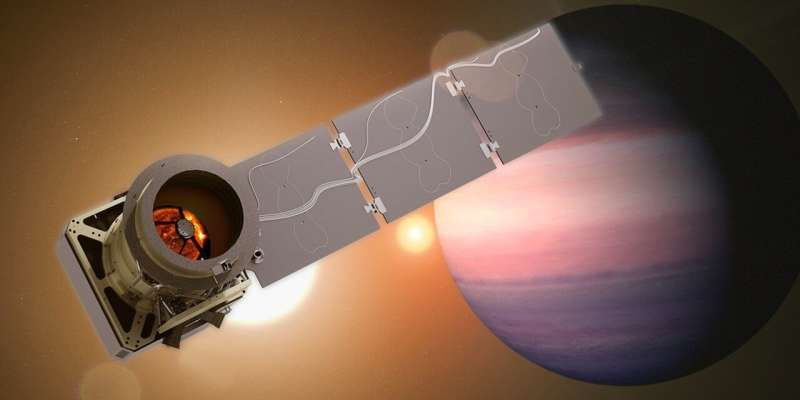

Pandora, a compact but highly capable space telescope developed to study planets beyond our solar system, is nearing a major turning point in its journey. Built as part of the University of Arizona’s long legacy of space science missions, the satellite has officially cleared its final major pre-launch milestone and is now fully integrated into its launch vehicle. Pandora has been mounted inside a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and is awaiting liftoff from Space Launch Complex 4E at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. The launch window opens at 6:19 a.m. Arizona time (8:19 a.m. EST) on Sunday, January 11, with SpaceX providing a live broadcast of the event.

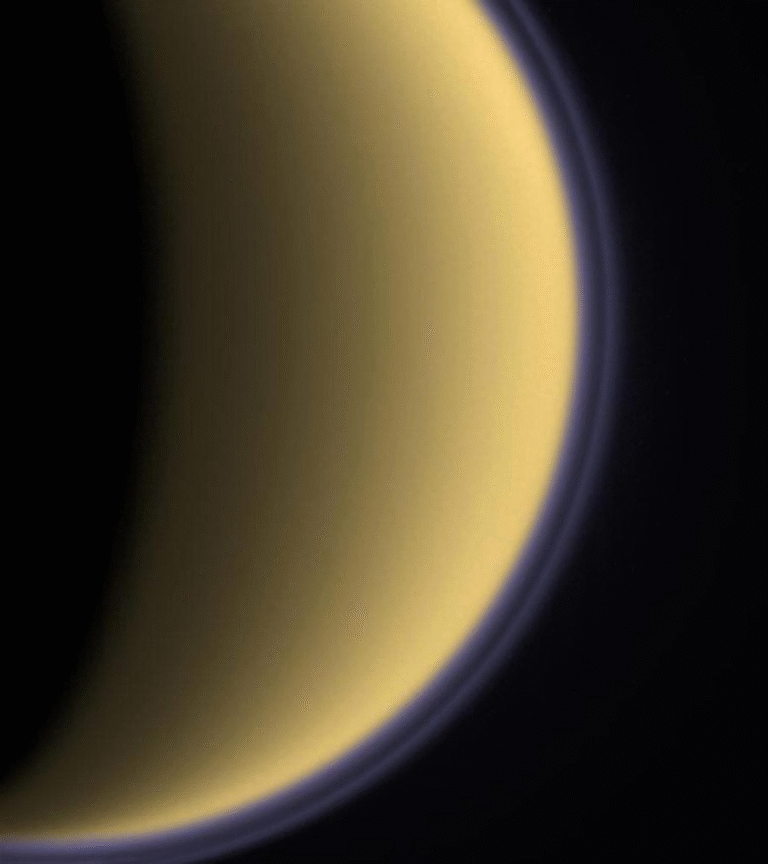

Roughly the size of a household refrigerator, Pandora may be small compared to flagship observatories, but its scientific ambitions are anything but. The mission is designed to perform detailed atmospheric studies of at least 20 known exoplanets, focusing especially on the presence of water vapor, clouds, and atmospheric hazes. These planets orbit stars far beyond our solar system, many dozens or even hundreds of light-years away, making direct observation extremely challenging.

At the heart of Pandora is a telescope equipped with an 18-inch mirror and a suite of instruments capable of analyzing light with extraordinary precision. By breaking down starlight into its component colors—a technique known as spectroscopy—Pandora can identify chemical signatures that reveal what an exoplanet’s atmosphere is made of. At the same time, the satellite can detect incredibly subtle changes in a star’s brightness, which occur when a planet passes in front of it from our point of view, an event known as a transit.

What makes Pandora especially significant is that it is the first space telescope built specifically for long-duration, multi-color observations of starlight filtered through exoplanet atmospheres. This design allows scientists to study planets and their host stars together, rather than treating the star as a simple, uniform light source. According to mission scientists, this approach is critical because stars are far from perfect spheres of steady light. Their surfaces are often mottled with star spots, bright regions, and turbulent plasma, all of which can distort measurements of a planet’s atmosphere.

Pandora’s data will play a crucial role in helping scientists interpret observations from earlier and ongoing missions such as NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope. By providing a clearer understanding of how stellar activity influences atmospheric measurements, Pandora will help researchers separate what belongs to the planet from what belongs to the star. This is a key step toward accurately characterizing distant worlds and, eventually, identifying planets that might be suitable for life.

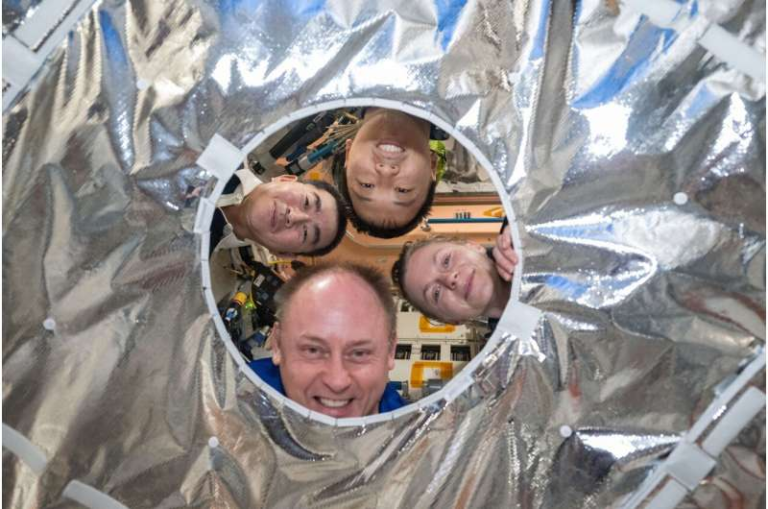

The mission was selected in 2021 as one of NASA’s inaugural Astrophysics Pioneers missions, a program designed to support fast-paced, lower-cost space missions that tackle emerging scientific questions. A distinctive feature of Pandora is its emphasis on developing future leaders in space science. More than half of the mission’s leadership roles are filled by early-career scientists and engineers, giving them hands-on experience running a space mission from start to finish.

After launch, Pandora will enter low Earth orbit, where it will spend about one month undergoing commissioning. During this phase, engineers will test and calibrate the spacecraft’s systems to ensure everything is functioning as expected. Once commissioning is complete, Pandora will begin its one-year prime science mission, and all of the data it collects will be made publicly available.

Mission operations will be handled by the University of Arizona’s Multi-Mission Operation Center (MMOC), part of the Arizona Space Institute. Located in the university’s Advanced Research Building, the MMOC will manage Pandora’s daily operations, track the spacecraft in real time, monitor telemetry, and assess overall spacecraft health. This marks the first orbiting astrophysics mission to be operated from the university’s new Mission Operations Center, building on the institution’s experience with previous missions such as OSIRIS-REx and the PHOENIX Mars Lander.

Pandora’s observing strategy is both methodical and intensive. For each of its 20 target systems, the satellite will stare continuously for about 24 hours, capturing a full planetary transit and the surrounding stellar activity. This process will be repeated 10 times per system, creating a rich dataset that allows scientists to identify patterns, reduce noise, and improve confidence in their measurements. The resulting data will form a strong foundation for interpreting results from James Webb and future missions focused on finding potentially habitable worlds.

Although Pandora is not designed to search directly for life, its measurements will look for key atmospheric components such as water vapor and will closely examine the behavior of host stars. Understanding the star is just as important as understanding the planet, because stellar variability can easily masquerade as—or obscure—true planetary signals.

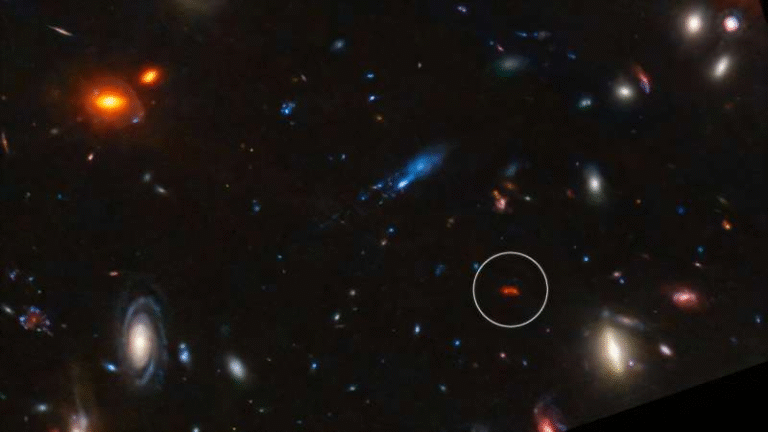

To appreciate why Pandora is needed, it helps to look at the broader history of exoplanet science. Just over three decades ago, astronomers had no confirmed evidence that planets existed outside our solar system. That changed in 1992, when the first exoplanet was discovered, triggering an explosion of discoveries. Today, scientists have identified more than 6,000 exoplanets, ranging from massive gas giants to small, rocky worlds that resemble Earth in size.

Because of the immense distances involved, most exoplanets cannot be seen directly. Instead, astronomers rely on indirect methods, with the transit method being one of the most powerful. By measuring the tiny dip in a star’s brightness when a planet crosses its face, scientists can infer the planet’s size and orbit. When combined with spectroscopy, this method can also reveal what chemicals are present in the planet’s atmosphere.

The challenge, however, is that stars themselves are complex and dynamic. If a planet transits across a relatively “clean” part of a star, the signal looks very different than if it crosses a region covered in spots or bright patches. Without accounting for this, scientists risk misinterpreting atmospheric data. Pandora is the first mission specifically designed to solve this problem by observing stars and planets together, across multiple wavelengths, over long periods of time.

With Pandora poised for launch, researchers see the mission as a major step forward in humanity’s effort to understand worlds beyond our own. By refining how we study exoplanet atmospheres and their host stars, Pandora will help shape the next generation of space telescopes and bring us closer to answering one of science’s biggest questions: how common are worlds like Earth in our galaxy?

Research reference:

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/pandora/