Protostars Carve Out Homes in the Orion Molecular Cloud

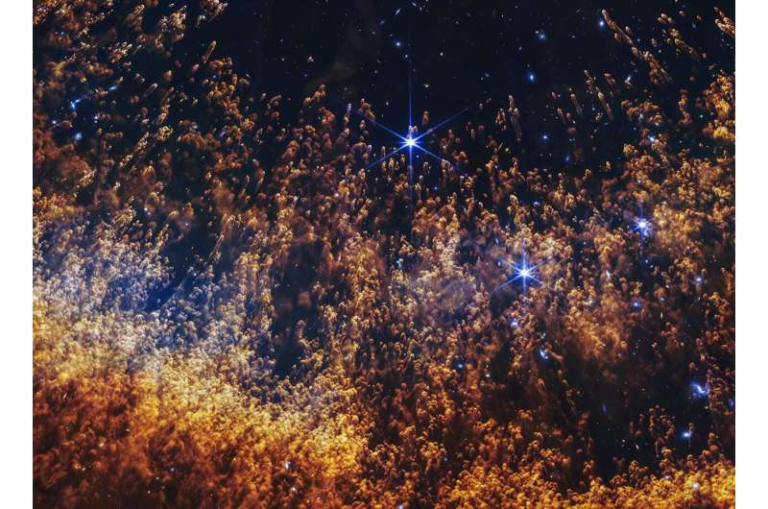

Young stars do not switch on overnight. Long before they become stable, main-sequence stars like our Sun, they spend hundreds of thousands of years in an earlier phase known as the protostar stage. During this time, they are still gathering mass from the cold, dense molecular clouds that gave them birth. New observations from the Hubble Space Telescope now show that even at this early stage, protostars are anything but quiet. Instead, they actively reshape their surroundings, carving out vast cavities in space inside one of the most famous stellar nurseries in our galaxy: the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex (OMC).

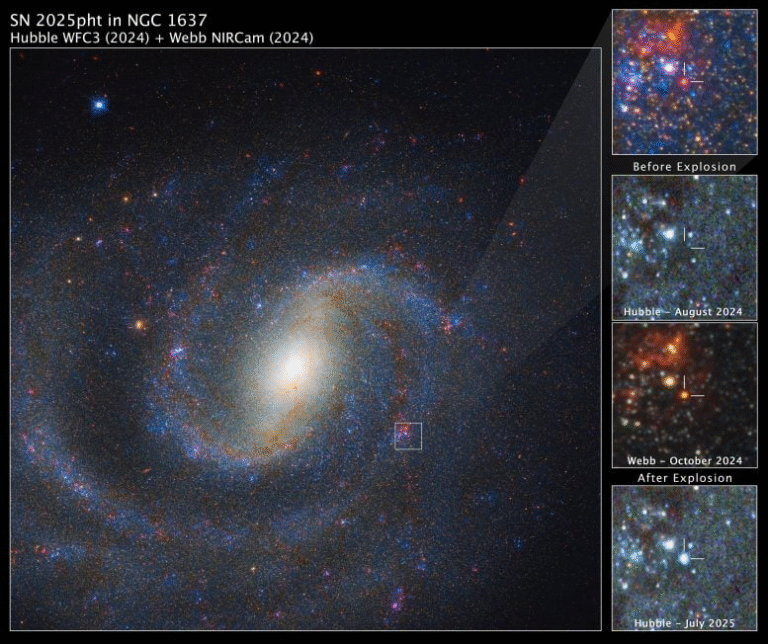

The newly released Hubble images focus on three protostars embedded deep within Orion, a region located about 1,300 light-years from Earth and widely regarded as one of the most active nearby star-forming environments. These images reveal dramatic, cavern-like structures carved into surrounding gas and dust, offering astronomers new clues about how young stars interact with their environments long before nuclear fusion begins in their cores.

What Makes a Protostar Different From a Star?

A protostar is essentially a star in the making. It forms when gravity pulls together gas and dust inside a molecular cloud, creating a dense core that continues to grow as it accretes more material. At this stage, the protostar is not yet hot enough to fuse hydrogen into helium, the defining process of main-sequence stars.

Despite this, protostars are far from passive. As they pull in material, they also release enormous amounts of energy into their surroundings through powerful outflows. These outflows come in two main forms: tightly focused jets and broader stellar winds. Together, they play a crucial role in shaping the protostar’s immediate environment.

Jets, Winds, and Carved Cavities

Astronomers have long known that gas falling toward a protostar does not drop straight onto its surface. Instead, it first forms a rotating disk around the young star. What remains uncertain is exactly how material moves from this disk onto the protostar itself.

What is clear, however, is that not all of the incoming material stays. Some of it is violently expelled back into space. Highly focused jets shoot out from the protostar’s poles at extreme speeds, guided by the star’s magnetic fields. These jets are composed mostly of hydrogen and are among the most visually striking features seen in star-forming regions.

In addition to jets, protostars also generate wide-angle stellar winds that flow outward in many directions. These winds are significantly stronger than the solar wind produced by mature stars like the Sun. Together, jets and winds push away gas and dust, hollowing out bubbles, tunnels, and cavern-like voids within the surrounding molecular cloud.

The new Hubble images capture these cavities in stunning detail. Bright cavity walls glow as light from the protostar reflects off dust and ionized gas, while background stars sparkle beyond the excavated regions. The visuals provide some of the clearest evidence yet of how young stars physically sculpt their birth environments.

Surprising Results From the Orion Study

One of the goals of this research was to better understand how these cavities evolve over time. Astronomers expected that as protostars aged and continued emitting jets and winds, the cavities they carved would gradually grow larger.

Surprisingly, the observations did not support this assumption. The researchers found that the cavities did not increase in size as the protostars progressed through later stages of formation. This challenges earlier ideas about how stellar feedback influences star-forming regions.

At the same time, scientists have observed that protostars experience a decline in mass accretion rates as they age. Additionally, the overall star formation rate in the Orion Molecular Cloud has slowed over time. However, the new findings indicate that neither of these trends can be directly explained by jets and winds clearing out surrounding material.

In other words, while protostellar outflows clearly shape local environments, they may not be the dominant factor controlling how fast stars grow or why star formation slows down across entire molecular clouds.

Why Orion Matters So Much

The Orion Molecular Cloud Complex is a cosmic laboratory for studying star formation. It contains hundreds of protostars and thousands of young stars at various stages of development. Because it is relatively close to Earth, astronomers can observe it in exceptional detail across many wavelengths, from infrared to visible light.

By studying Orion, scientists gain insights into processes that likely occurred when our own Sun was born. Evidence suggests the Sun formed in a clustered environment similar to Orion, surrounded by sibling stars that later drifted apart. During its protostellar phase, the Sun would have launched jets and winds of its own, shaping nearby gas and dust in much the same way as the protostars seen in these new Hubble images.

From Violent Beginnings to Quiet Stability

As protostars mature, their behavior changes dramatically. Early on, they can undergo episodes of sudden brightening accompanied by stronger winds and enhanced mass ejection. Over time, as they approach the main sequence and begin sustained hydrogen fusion, these outflows weaken.

Eventually, the surrounding molecular cloud disperses, and much of the evidence of the star’s turbulent youth disappears. What remains is a stable, long-lived main-sequence star, often far removed from its original siblings. This process explains why stars like the Sun now appear isolated, even though they formed in crowded stellar nurseries.

The Bigger Picture of Star Formation

The findings from Orion highlight how complex and interconnected star formation really is. Jets and winds clearly matter, but they are only part of a larger system involving gravity, magnetic fields, turbulence within molecular clouds, and interactions between neighboring stars.

Understanding these processes is especially important for explaining how massive stars form. The strongest jets are associated with the most massive protostars, yet the formation of massive stars remains less well understood than that of smaller ones like the Sun. Studies like this help refine theoretical models and guide future observations with next-generation telescopes.

Looking Ahead

These new Hubble observations mark another step forward in unraveling the early lives of stars. By combining detailed imaging with theoretical models and future data from observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers hope to finally answer long-standing questions about how stars gather their mass, regulate their growth, and influence the galaxies they inhabit.

For now, the message is clear: even before they shine through nuclear fusion, protostars are powerful architects, carving out homes within the cosmic clouds that give them life.

Research paper:

Carrasco-González et al. 2025, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (ApJL)

https://iopscience.iop.org/journal/2041-8205