Radio Telescopes Reveal Invisible Gas Around a Record-Breaking Cosmic Explosion

Astronomers have uncovered striking new details about one of the most powerful cosmic explosions ever observed, thanks to radio telescopes that can see what ordinary optical instruments cannot. The event, known as AT2024wpp and nicknamed “the Whippet,” belongs to a rare and puzzling class of phenomena called Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients (LFBOTs). These explosions appear suddenly, shine with extraordinary intensity, and then fade away in just days. What makes AT2024wpp special is not just its brightness, but what it reveals about how some of the most extreme explosions in the universe actually work.

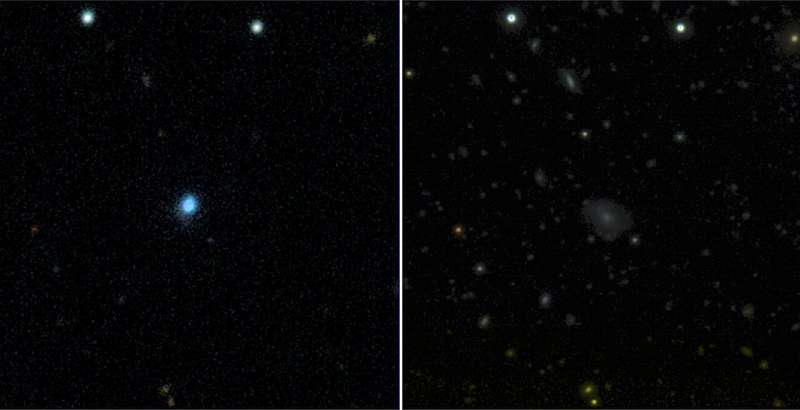

AT2024wpp was first detected in September 2024 by the Zwicky Transient Facility at Palomar Observatory, a project designed to scan the sky for short-lived cosmic events. Astronomers noticed a sudden burst of light coming from a distant galaxy, far brighter than a typical supernova and rising much faster. Follow-up observations quickly showed that this was something unusual. The source was extremely hot, intensely blue, and producing powerful X-ray radiation, all classic signatures of an LFBOT.

What immediately stood out was just how luminous the explosion was. AT2024wpp briefly radiated energy at a rate that outshone 100 billion suns, making it the brightest LFBOT ever observed. In terms of raw power, it rivaled only the most extreme gamma-ray bursts and tidal disruption events, where stars are torn apart by black holes. This placed AT2024wpp in a league of its own and made it an ideal target for deeper investigation.

Astronomers around the world quickly mobilized a wide range of telescopes to study the event across the electromagnetic spectrum. Optical and ultraviolet observations from ground-based observatories and the Hubble Space Telescope showed something puzzling. Despite the immense brightness of the explosion, the early spectra were almost completely smooth. There were no strong chemical fingerprints—no clear lines from hydrogen, helium, or heavier elements that normally reveal what kind of material surrounds an exploding star.

This was unexpected. One leading theory for LFBOTs suggested that they occur when an explosion slams into dense shells of gas that massive stars shed shortly before dying. Such interactions should leave obvious spectral signatures. But AT2024wpp seemed to contradict that idea. If there was dense gas nearby, why wasn’t it showing up in the data?

The answer came from observations at longer wavelengths. Using the U.S. National Science Foundation Very Large Array (VLA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers were able to probe the environment around the explosion in radio and millimeter light. What they found completely changed the picture.

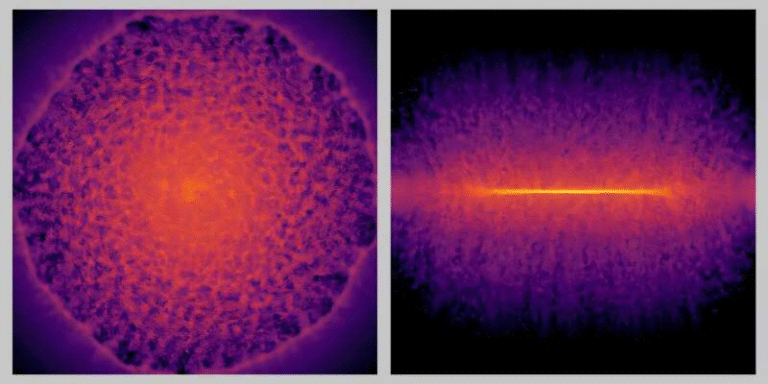

The radio data revealed a shock wave racing outward at about one-fifth the speed of light, plowing into a dense cocoon of gas surrounding the explosion site. In other words, the gas was there all along—it was just invisible to optical and ultraviolet telescopes. Radio instruments are sensitive to free, energetic electrons, which allowed them to detect this material even when traditional methods failed.

This resolved the apparent contradiction. The explosion produced such intense X-ray radiation that it stripped electrons from the surrounding atoms, leaving the gas in a highly ionized state. When gas is ionized to this degree, it no longer produces the familiar spectral lines astronomers rely on to identify chemical elements. To optical and ultraviolet telescopes, the environment looked nearly empty. To radio telescopes, it was anything but.

The radio observations also showed that the emission faded sharply after about six months. This indicated that the shock wave had reached the outer edge of the dense gas bubble. Beyond that boundary, there was far less material to interact with, causing the radio signal to drop off quickly. This provided a rare glimpse into the structure of the environment shaped by the star before its destruction.

By combining all of these observations, astronomers concluded that AT2024wpp was powered by a dramatic interaction between a massive star and a black hole. In this scenario, the black hole spiraled into its stellar companion and began tearing it apart. As the star lost its outer layers, it created a thick shell of gas around the system. When the star’s core was finally disrupted, the remaining debris formed a hot accretion disk around the black hole.

This accretion process generated the enormous X-ray output needed to ionize the surrounding gas and hide its chemical signatures. At the same time, powerful winds launched from the disk slammed into the previously ejected material, producing the bright radio and millimeter emission detected by the VLA and ALMA. The result was an explosion that was both extraordinarily luminous and deceptively difficult to interpret without multi-wavelength data.

As the event faded, later observations from the Keck Observatory, Magellan telescopes, and the Very Large Telescope began to reveal faint spectral features that were absent at early times. Subtle signs of hydrogen and helium emerged, including helium moving at speeds greater than 6,000 kilometers per second. These late-time signals suggest that some dense structures survived the initial blast. Possibilities include a stream of material from the torn-apart stellar core or even the presence of a third star in the system.

AT2024wpp has become one of the most compelling pieces of evidence yet that at least some LFBOTs are linked to black hole accretion events, rather than conventional supernova explosions. It also highlights the importance of radio astronomy in modern astrophysics. Without radio and millimeter observations, the dense environment around this explosion would have remained hidden, leading to incomplete or even misleading conclusions.

What Are Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients?

LFBOTs are among the most mysterious transient phenomena known. They rise to peak brightness in just days, shine with extreme intensity, and fade rapidly, leaving astronomers with only a short window to study them. Their blue color indicates very high temperatures, and their energy output often exceeds what standard stellar explosions can easily explain. Only a handful of well-observed examples exist, making each new event critically important.

Why Radio Telescopes Matter

Events like AT2024wpp demonstrate that the universe can hide crucial information in forms of matter that are effectively invisible at certain wavelengths. Radio telescopes excel at detecting ionized gas and energetic particles, allowing scientists to probe environments shaped by extreme radiation and violent interactions. As more sensitive radio facilities come online, astronomers expect to uncover many more hidden aspects of cosmic explosions.

AT2024wpp stands as a powerful reminder that the most dramatic events in the universe often require every available tool to fully understand. By looking beyond visible light, astronomers are finally beginning to piece together the true nature of these fleeting but extraordinary cosmic blasts.

Research paper:

https://www.astro.ljmu.ac.uk/~aridperl/draft/AT2024wpp.pdf