Scientists Have Finally Detected a Devastating Stellar Storm on a Red Dwarf Star Beyond Our Solar System

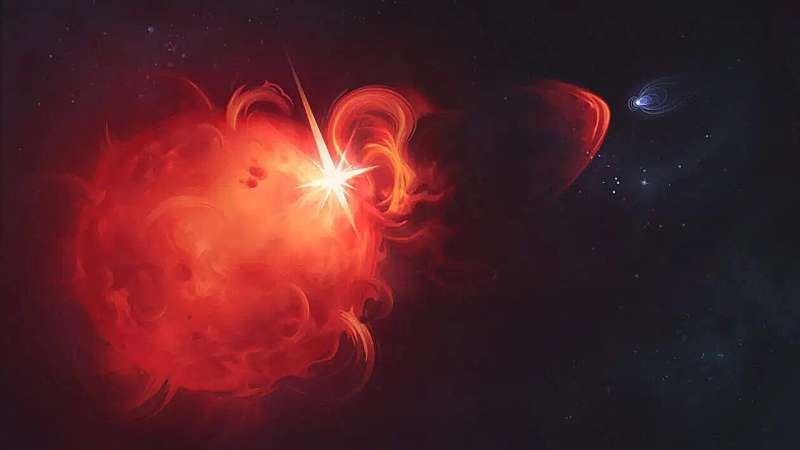

Astronomers have achieved something that has long been suspected but never directly observed before: the first confirmed detection of a coronal mass ejection (CME) from a star other than our Sun. This groundbreaking observation comes from a small yet extremely active red dwarf star, and the implications stretch far beyond stellar physics. The discovery forces scientists to rethink how safe planets around these stars might actually be, even if they sit comfortably inside the so-called habitable zone.

On Earth, CMEs are dramatic but usually manageable events. They can spark vivid auroras, disrupt radio communications, and occasionally pose risks to satellites and power grids. Around other stars, however, these violent eruptions could be far more destructive—potentially stripping entire planetary atmospheres and sterilizing nearby worlds. This new detection offers the first solid evidence that such extreme space weather really does occur around red dwarf stars.

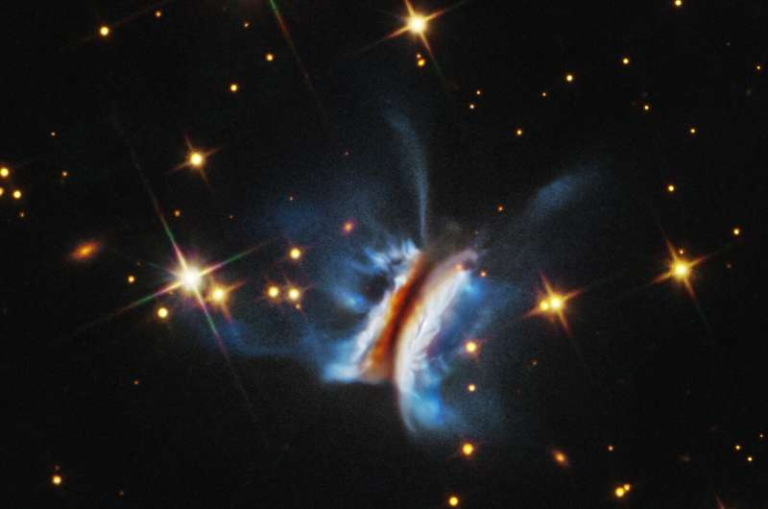

The First Direct Evidence of a Stellar Coronal Mass Ejection

Until now, scientists only had indirect hints that stars beyond the Sun could produce CMEs. These clues came from subtle changes in light or shifts in spectral lines, but none provided definitive proof that stellar material was being violently hurled into space.

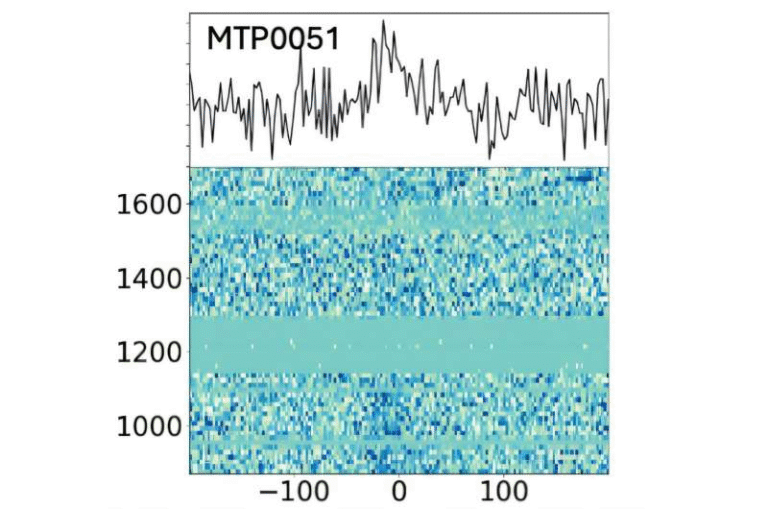

That changed with the detection of a Type II radio burst, a well-known signature of CMEs in our own solar system. These radio bursts are produced when a powerful shock wave travels through a star’s corona, accelerating charged particles and emitting radio waves that drift downward in frequency as the shock moves outward.

This time, the signal did not come from the Sun. It came from a nearby red dwarf star, marking the first unambiguous observation of a stellar CME beyond our solar system.

Meet the Star Behind the Storm

The source of the eruption is an M-class red dwarf star named StKM-1262. It has about 60% the mass of the Sun and lies roughly 130 light-years away from Earth. The star sits near the boundary between the constellations Draco and Boötes, just inside Draco.

As of now, no exoplanets are known to orbit this star, but its behavior still provides crucial insight into what planets around similar stars might experience. Red dwarfs are the most common type of star in the universe, making up around 75% of all main-sequence stars. Even though they are faint and invisible to the naked eye from Earth, they dominate the galaxy in sheer numbers.

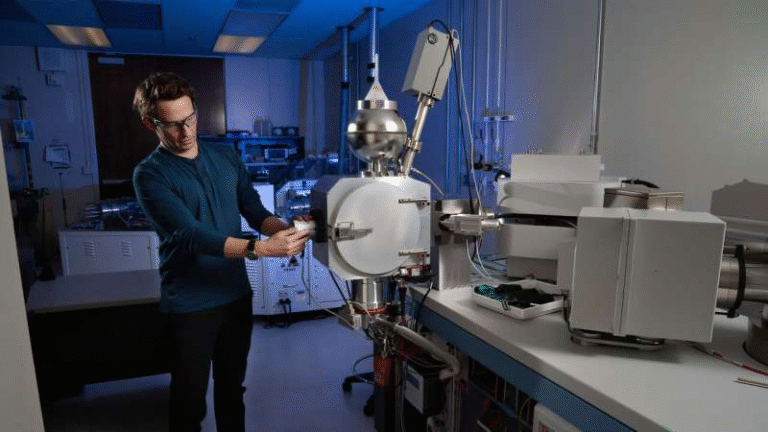

How Astronomers Detected the Storm

The detection was made using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), a powerful radio telescope network consisting of around 20,000 dipole antennas spread across the Netherlands and neighboring European countries. LOFAR was operating as part of the LOFAR Two-Meter Sky Survey, which observed approximately 86,000 stars within 100 parsecs (326 light-years) of Earth over an eight-hour period.

During this survey, astronomers detected a bright, fast-drifting radio signal consistent with a Type II radio burst. This signal traced the movement of a shock wave through the star’s corona, allowing researchers to follow the CME as it expanded outward.

To complement the radio data, the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton space telescope observed the event in X-ray wavelengths. The X-ray observations helped scientists estimate the density and structure of the star’s corona, making it possible to calculate the physical properties of the CME itself.

An Explosion Far More Powerful Than the Sun’s

What makes this discovery especially alarming is the sheer intensity of the event. The detected radio emission was estimated to be 10 to 100,000 times brighter than similar bursts produced by CMEs from the Sun.

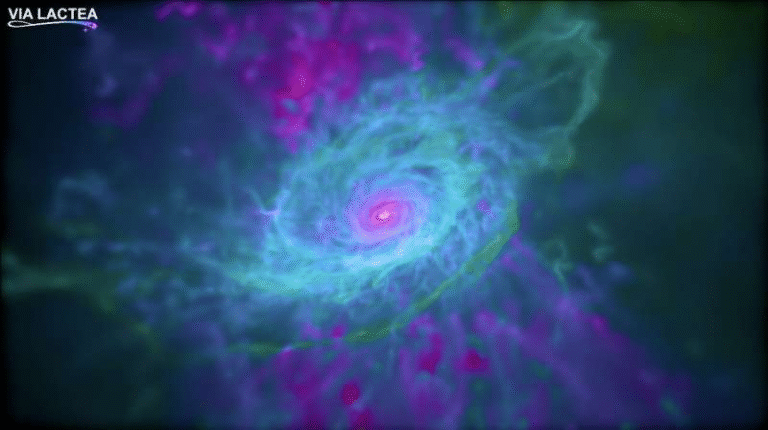

Red dwarf stars are believed to be fully convective, meaning their interiors churn in a way that generates extremely strong magnetic fields. These magnetic fields can store enormous amounts of energy, which is then released in massive flares and CMEs.

In practical terms, this means that a CME from a red dwarf can be far more violent than anything Earth typically experiences from the Sun. If a planet were positioned in the path of such an eruption, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Why This Matters for Exoplanets and Habitability

Planets in the habitable zone of red dwarf stars orbit much closer to their host star than Earth does to the Sun. This is because red dwarfs are cooler and dimmer, so a planet must stay close to receive enough warmth for liquid water.

That proximity, however, comes at a cost. A powerful CME can compress a planet’s magnetosphere, potentially all the way down to the surface. Over time, repeated blasts could strip away the planet’s atmosphere, leaving it barren and lifeless.

Even if a red dwarf only produces a giant CME once every few hundred years, life as we know it needs millions to billions of years to evolve. Frequent exposure to such extreme space weather could make long-term habitability unlikely unless a planet has exceptionally strong magnetic shielding.

This discovery reinforces the idea that habitability is not just about liquid water. The magnetic and radiation environment of a star plays a crucial role in determining whether a planet can hold onto its atmosphere and support life.

Red Dwarfs: Common, Long-Lived, and Dangerous

Red dwarfs may burn their fuel slowly, with lifespans measured in trillions of years, far exceeding the current 13.8-billion-year age of the universe. On paper, that longevity seems ideal for life to develop.

But their violent magnetic activity presents a serious downside. Many confirmed exoplanets, including those in famous systems like TRAPPIST-1 and TOI-2267, orbit red dwarfs. This discovery adds weight to concerns that such systems may be hostile environments, despite appearing promising based on temperature alone.

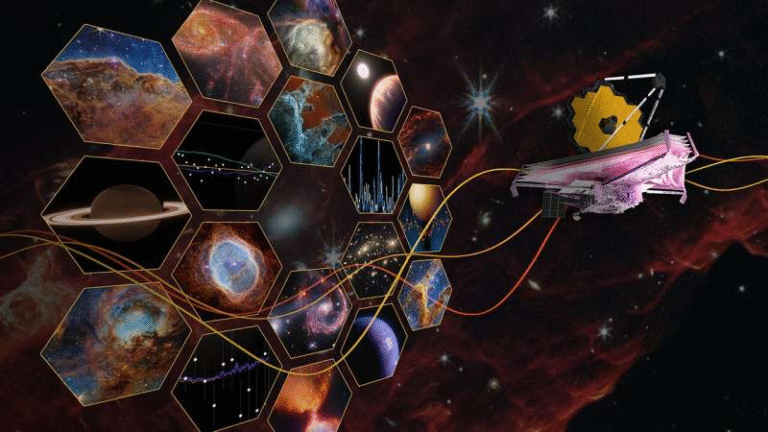

Opening a New Era of Stellar Space Weather Research

This detection represents a major step forward in understanding stellar space weather beyond the Sun. With direct observations now possible, astronomers can begin building real statistics on how often red dwarfs produce massive CMEs and how energetic those events truly are.

Future instruments will take this research even further. The Square Kilometre Array (SKA), currently under construction in South Africa and Australia, is expected to come online for scientific observations in 2027. Scientists anticipate that the SKA could detect dozens to hundreds of stellar CMEs in its very first year, dramatically expanding our understanding of how stars affect their surrounding planets.

At the same time, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is working to detect and analyze atmospheres around Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting red dwarf stars. Together, these efforts may finally answer how common truly habitable worlds are in the galaxy.

A Small Discovery With Big Consequences

This first direct detection of a stellar CME confirms what many researchers have long suspected: red dwarf stars can unleash planet-threatening storms. While they may be the most common stars in the universe, they might also be some of the toughest neighborhoods for life to survive.

In that context, our own relatively calm G-type yellow dwarf Sun may be a bigger advantage than we once realized.

Research Paper:

Radio Burst from a Stellar Coronal Mass Ejection (Nature, 2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09715-3