Scientists Use Icelandic Mudrocks to Prepare for Future Mars Sample Analysis

Scientists are taking a practical and highly detailed approach to preparing for the day when Martian rock samples finally reach Earth. Instead of waiting for NASA’s Mars Sample Return mission—which will take at least a decade from the moment Perseverance collected its samples—researchers are studying mudrocks in Iceland that closely resemble what we expect to find on Mars. These Icelandic sediments offer a valuable real-world testing ground for refining the high-resolution techniques needed to properly analyze fine-grained Martian materials sealed inside protective metal tubes.

These new findings come from an international team involving the University of Maryland, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA Johnson Space Center, University of Göttingen, Chungbuk National University, and the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Their study, recently published in American Mineralogist, goes deeper into sediment structure and chemistry than earlier efforts, uncovering details that were previously invisible to scientists.

Why Iceland Is a Mars Analog

Iceland has become one of the most scientifically valuable landscapes for Mars research. The areas studied are dominated by basalt, the same volcanic rock that makes up much of the Martian crust and has been confirmed by both the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers. Beyond the rock type, the environment is shaped by glaciers, glacial meltwater, rivers, and volcanic activity—features that mirror ancient Mars in many ways.

The Icelandic samples used in this research were collected from a glacio-fluvial watershed in southwest Iceland, where sediments move from glaciers through river systems before settling downstream. This environment produces mudrocks—sedimentary rocks formed from tiny clay-size particles—which are also common on Mars and other rocky bodies in the Solar System.

These sediments form as glaciers scrape rocks into fine particles. When the ice melts, the sediments are washed into rivers and deposited along their path. Despite forming through familiar processes, these tiny grains are incredibly difficult to analyze because they are mixtures of crystalline minerals, nanocrystalline phases, and amorphous materials. Many of these components are smaller than four micrometers, which earlier studies could not fully characterize.

The High-Resolution Techniques Behind the Study

The team used a suite of advanced tools to uncover the hidden complexity of these mudrocks:

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For ultrastructural imaging at the nanoscale. - Powder X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

For identifying crystalline minerals. - X-Ray Pair Distribution Function (PDF) Analysis at NSLS-II

Essential for detecting short-range atomic structure in disordered or amorphous materials. - Submicron Resolution X-Ray Spectroscopy (SRX)

For mapping elemental composition and oxidation states at extremely small scales.

These methods revealed that the sediments contain mixtures far more complex than previously recognized. Instead of single mineral grains, many particles were combinations of multiple phases. The team identified crystalline clays like kaolinite and mixed-layer kaolinite–smectite, as well as amorphous or nanocrystalline materials with compositions similar to allophane, ferrihydrite, halloysite, and hisingerite.

The SRX beamline also showed that every sample had varying levels of iron and calcium, but their distribution changed depending on where the samples were collected in the watershed. The oxidation states of iron varied too, offering clues about weathering conditions and environmental exposure.

What These Findings Mean for Mars Samples

When Mars samples eventually reach Earth, they will be sealed in airtight metal tubes to prevent contamination or exposure to Earth’s atmosphere. High-energy X-rays will be required just to see inside them. Because scientists will not be able to open these tubes casually, Earth-based analysis must be extremely precise.

This Iceland study shows that:

- Martian mudrocks will be more complex than they appear.

Tiny grains may include multiple minerals and amorphous phases. - Standard laboratory techniques will not be enough.

Proper interpretation will require powerful tools like synchrotron X-ray methods. - Environmental history will be encoded at a microscopic level.

Each grain may carry distinct clues about past water, climate, temperature changes, and chemical weathering. - Juvenile mineral phases may persist on Mars due to cold, dry conditions.

Understanding why these phases survive helps researchers interpret Martian geological timelines.

Iceland’s combination of basaltic terrain, glacial activity, and cold climate mirrors conditions believed to exist on ancient Mars, making it one of the closest “real Earth” analogs for studying processes that shaped Martian sediments.

Why Mudrocks Matter for Planetary Science

Mudrocks are more than just fine-grained sediment—they are time capsules. Because tiny mineral particles respond quickly to environmental changes, they preserve subtle information about conditions at the time of their formation. On Mars, mudrocks could answer major questions:

- Did Mars once support sustained liquid water?

- How long did volcanic and glacial processes remain active?

- How quickly did climate change occur?

- Are there chemical environments that could have supported early microbial life?

Understanding mudrock formation on Earth helps scientists create a baseline for interpreting Martian versions. The Iceland study suggests that earlier assumptions about “simple” layers may underestimate how dynamic sedimentary environments really are.

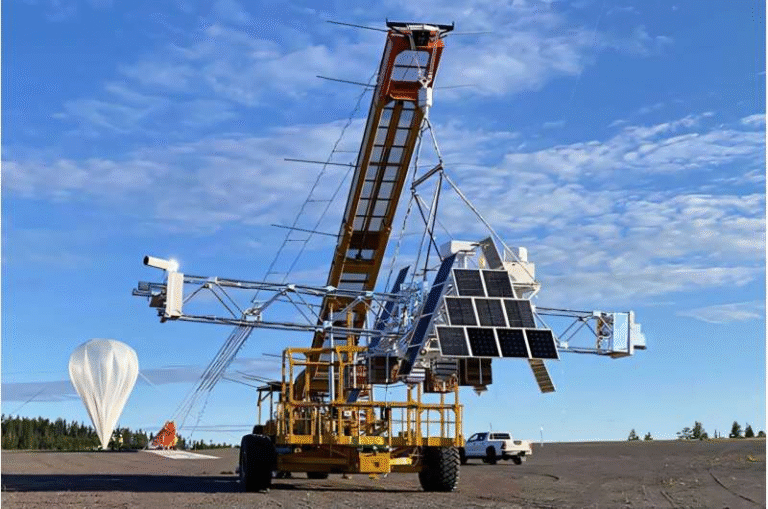

The Bigger Picture: Preparing for Mars Sample Return

NASA’s Mars Sample Return Campaign aims to bring back rock cores collected by Perseverance as early as the late 2030s. Because returning these samples is extraordinarily difficult and expensive, scientists must be certain that every analysis performed on them is accurate and methodologically sound.

This study’s breakthroughs highlight the need to:

- Continue refining high-resolution analytical methods

- Expand analog studies to other volcanic and glacial landscapes

- Understand how sediment transforms from source to sink

- Anticipate the complexity of unaltered Martian samples

The team is already exploring other basaltic regions, such as Lanzarote in Spain, where a warmer climate and stronger weathering could introduce additional variables relevant to Mars research.

Additional Background: Why Basaltic Sediments Resemble Martian Terrain

Basalt is one of the most common volcanic rocks in the Solar System. Mars’ crust is dominated by basaltic compositions, and many of its sedimentary deposits come from the breakdown of basalt. On Earth, basalt in cold, water-rich environments forms alteration minerals similar to those found by Martian rovers—such as smectite clays, silica-rich amorphous phases, and iron oxides.

These materials can indicate:

- The presence of ancient water

- Potential habitable environments

- Chemical reactions between water and rock

- Long-term climate patterns

Because Mars lacks plate tectonics and has had little geological recycling, many of these ancient signatures may still be preserved.

Research Reference

High-resolution analysis of clay minerals and amorphous materials in martian analog environments