Scientists Warn That Low Earth Orbit Could Face a Catastrophic Satellite Collision in Just 2.8 Days

The space around our planet may look vast and empty, but according to a new scientific study, low Earth orbit (LEO) has become a surprisingly fragile and tightly packed environment. Researchers are now warning that if satellite operators were to lose control of their spacecraft, a catastrophic collision could occur in as little as 2.8 days. That startling number highlights how close today’s satellite infrastructure is to a cascading disaster.

This warning comes from a recent research paper led by Sarah Thiele, formerly a PhD student at the University of British Columbia and now a researcher at Princeton University, along with her co-authors. The team describes the current state of satellite megaconstellations as an “orbital house of cards”—a system that works only as long as every part functions perfectly and continuously.

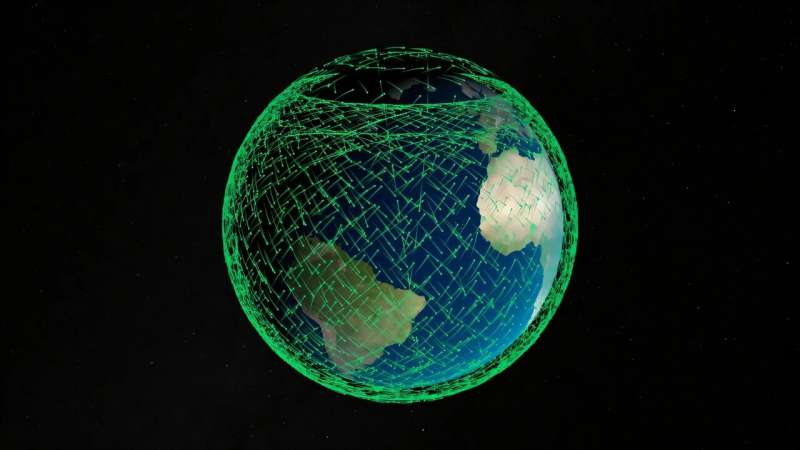

How Crowded Low Earth Orbit Has Become

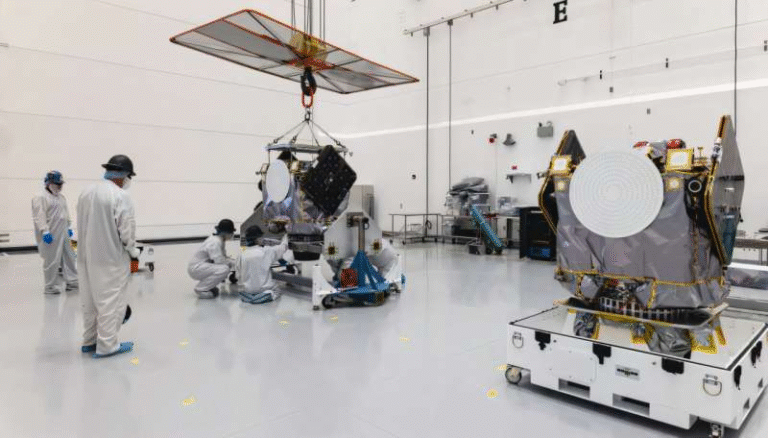

Low Earth orbit, generally defined as the region of space up to about 2,000 kilometers above Earth, is home to thousands of satellites. Over the past decade, the number of objects in this region has exploded due to the rise of megaconstellations, particularly large satellite networks designed to provide global internet coverage.

The study found that across all megaconstellations in LEO, a “close approach”—defined as two satellites passing within less than 1 kilometer of each other—now happens every 22 seconds. That is an astonishingly frequent event when you consider that each close approach carries some level of collision risk.

For Starlink alone, operated by SpaceX, these close approaches occur about once every 11 minutes. To manage this risk, satellites are constantly being nudged out of the way. On average, each Starlink satellite performs around 41 collision-avoidance maneuvers per year. These maneuvers are planned, monitored, and executed through continuous communication between satellites and operators on the ground.

At first glance, this may sound like a well-managed system doing exactly what it is designed to do. But engineers know that complex systems often fail at the edges, not during normal operations.

The Hidden Danger of “Edge Cases”

The research focuses heavily on scenarios where normal operations are disrupted—what engineers often call edge cases. One of the most concerning edge cases for satellites is solar storms.

Solar storms can affect satellites in two major ways. First, they heat Earth’s upper atmosphere, causing it to expand. This increases atmospheric drag on satellites in low orbits, making their paths less predictable and forcing them to burn more fuel to stay on course. Increased drag also raises uncertainty in orbital predictions, making collision avoidance more difficult.

During the powerful Gannon Storm in May 2024, more than half of all satellites in low Earth orbit had to expend fuel to reposition themselves in response to changing atmospheric conditions. Events like this are no longer rare anomalies; they are real-world stress tests for the orbital system.

Second, and more dangerously, solar storms can disrupt satellite navigation and communication systems. If a satellite cannot receive commands or determine its precise position, it cannot maneuver out of the way of other objects. Combine that loss of control with increased drag and positional uncertainty, and the risk of collision rises sharply.

Introducing the CRASH Clock

To quantify just how dangerous this situation could become, the researchers developed a new metric called the Collision Realization and Significant Harm (CRASH) Clock. This clock estimates how long it would take for a catastrophic satellite collision to occur if operators suddenly lost the ability to send avoidance commands.

As of June 2025, the CRASH Clock sits at approximately 2.8 days. In other words, if satellite operators lost control today, statistical modeling suggests that a major collision would likely occur in under three days.

For comparison, the researchers calculated that in 2018, before the rapid growth of megaconstellations, the CRASH Clock would have been around 121 days. The difference clearly shows how dramatically the orbital environment has changed in just a few years.

Even more alarming is another finding from the study: if operators lose control for just 24 hours, there is already a 30 percent chance of a catastrophic collision. Such a collision could serve as the initial trigger for a much larger and longer-lasting chain reaction.

The Specter of Kessler Syndrome

That chain reaction is often referred to as Kessler syndrome, a scenario in which debris from satellite collisions creates a cascading effect. Each collision generates fragments that can strike other satellites, producing even more debris. Over time, this could make certain orbital regions effectively unusable.

While Kessler syndrome itself would take decades to fully unfold, the study emphasizes that the seed event could happen very quickly. A single catastrophic collision involving large satellites could generate enough debris to permanently alter the safety of low Earth orbit.

This is not merely a theoretical concern. The researchers point out that solar storms offer little warning—often only a day or two at most. And if a storm were strong enough to knock out satellite control systems for longer than a few days, the consequences could be severe.

Lessons from History and a Sobering Thought

The strongest solar storm on record, the Carrington Event of 1859, occurred long before satellites existed. If an event of similar magnitude were to happen today, it could disrupt satellite control systems for far longer than the 2.8-day safety window identified by the CRASH Clock.

In that scenario, humanity could lose a significant portion of its satellite infrastructure, potentially cutting off communications, navigation, Earth observation, and space access for years or even generations.

Why This Matters Beyond Satellites

Modern life depends heavily on space-based systems. Satellites support GPS navigation, weather forecasting, disaster monitoring, scientific research, financial networks, and global communications. The study makes it clear that maintaining access to space now depends on continuous real-time control and coordination.

The benefits of megaconstellations are undeniable, but this research underscores the importance of realistic risk assessment, improved space traffic management, and international coordination. The orbital environment is no longer forgiving, and even short disruptions could have long-lasting consequences.

Understanding these risks is the first step toward making informed decisions about how we manage and protect Earth’s increasingly crowded neighborhood in space.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09643