Searching for Green Oceans and Purple Earths as NASA Plans a Telescope to Spot Life Beyond Earth

The search for life beyond our solar system is entering a new and far more detailed phase, and a recent scientific white paper makes it clear just how ambitious that search is becoming. Researchers working on NASA’s proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO) are arguing that future space telescopes must be powerful enough to detect not just atmospheres, but entire planetary surfaces—including oceans, continents, and even ancient forms of life that once dominated Earth itself.

This idea is explored in a newly released paper by the Living Worlds Working Group, a team tasked with defining the scientific requirements for HWO. Their work focuses on how different stages of life on Earth would appear if observed from many light-years away, and what kinds of instruments would be needed to recognize similar signs on exoplanets.

A Telescope Designed Specifically to Hunt for Habitable Worlds

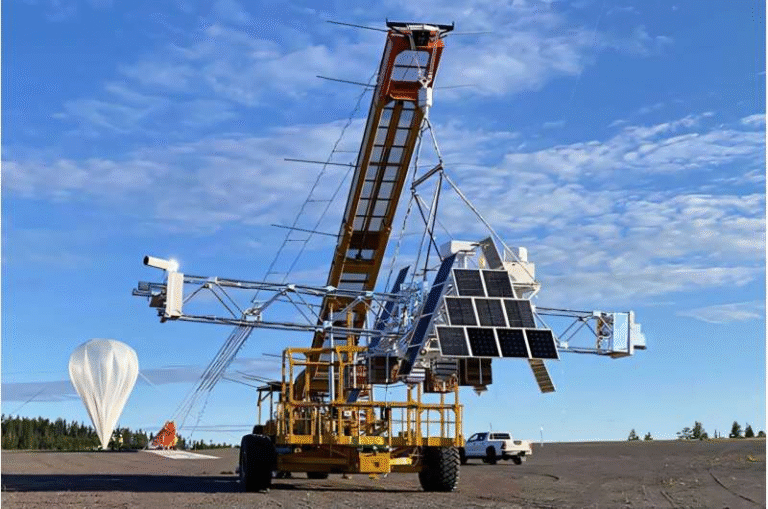

The Habitable Worlds Observatory is still in its early planning stages, and like most large NASA missions, its design is shaped by scientific goals, engineering constraints, and budget realities. White papers like this one are part of the early “horse-trading” phase, where scientists explain what they want the telescope to do and why those capabilities matter.

HWO is envisioned as one of the world’s most advanced exoplanet-hunting observatories, building on decades of discoveries made by missions like Kepler, TESS, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). But unlike JWST, which often studies planets as they pass in front of their stars, HWO is designed for direct imaging.

This difference is crucial. JWST typically analyzes starlight filtered through a planet’s atmosphere during a transit. HWO, on the other hand, would use a coronagraph—a device that blocks out the blinding light of a star—to directly observe the much fainter planet beside it. With enough sensitivity, this technique allows scientists to study not just atmospheres, but surface features as well.

Why Signal-to-Noise and Wavelength Range Matter So Much

The Living Worlds Working Group makes a strong case that HWO must achieve an extremely high signal-to-noise ratio while observing across a very wide range of wavelengths, spanning visible light and well into the near-infrared.

At first glance, this might sound like standard wish-list thinking. More light and better resolution are always helpful. But for HWO, these capabilities are not optional extras. They are essential for detecting specific surface biosignatures, subtle spectral features that could reveal the presence of life.

Many of these biosignatures only become visible when multiple wavelength ranges are observed together. A telescope that looks only at visible light, for example, could completely miss signs of certain biological processes that dominated Earth for billions of years.

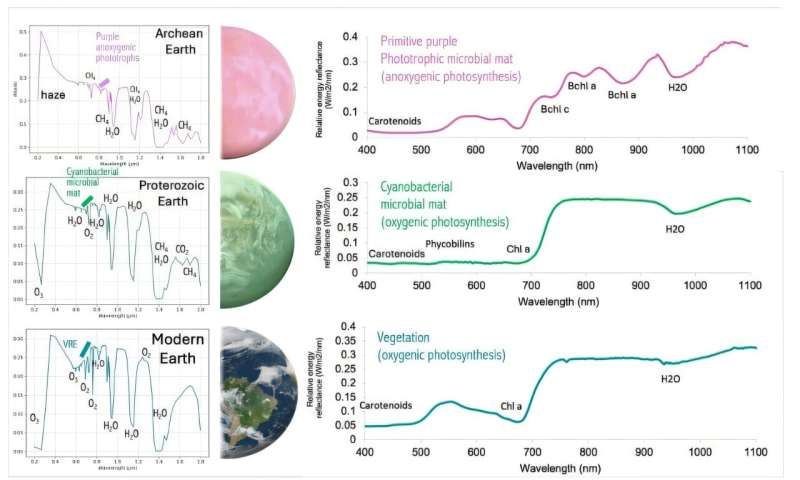

The Vegetation Red Edge and Modern Plant Life

One of the most well-known surface biosignatures is the Vegetation Red Edge. On Earth, plants absorb red light for photosynthesis but strongly reflect near-infrared light to avoid overheating. This creates a sharp spectral feature right at the boundary between red and infrared wavelengths.

From a distance, this “edge” would appear as a distinct jump in reflectance—essentially a fingerprint of plant life. Detecting it, however, requires instruments capable of measuring both visible and near-infrared light with high precision. Without that coverage, the signal simply disappears.

Purple Earths and the Earliest Photosynthesizers

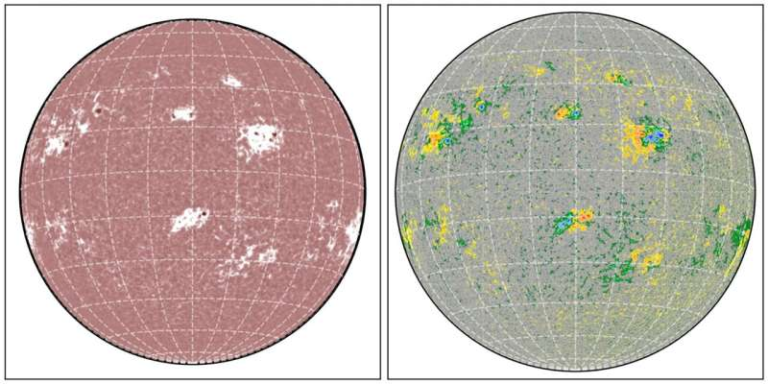

Long before green plants covered Earth’s surface, life may have looked very different. The paper highlights a fascinating earlier phase dominated by purple anoxygenic phototrophs, microbes that used bacteriochlorophylls and retinal-based pigments instead of modern chlorophyll.

These organisms absorbed green light and reflected red and blue wavelengths, giving them a purple appearance. Scientists believe this phase of life may have lasted for nearly 1.5 billion years, making it one of the longest chapters in Earth’s biological history.

Some descendants of these organisms still exist today, most famously Halobacteria, which can turn salt flats and shallow waters vivid shades of purple and pink. Importantly, these microbes absorb light deep into the infrared, meaning a telescope limited to visible wavelengths would miss them entirely.

The Green Ocean Hypothesis and Ancient Seas

Another major concept discussed in the paper is the green ocean hypothesis. Between roughly 4 and 2.5 billion years ago, Earth’s oceans may have looked dramatically different due to the chemistry of the early planet.

Hydrothermal vents released vast amounts of ferrous iron into the oceans. This iron absorbed red and blue light while reflecting green, potentially giving Earth’s oceans a greenish hue. During this time, cyanobacteria—some of the most important organisms in Earth’s history—developed pigments called phycobilins that allowed them to efficiently harvest this reflected green light.

From space, a planet dominated by green oceans covered in cyanobacteria could resemble one covered in vegetation. While that might seem confusing, both scenarios would still point to the presence of life.

The Challenge of False Positives

Not every spectral feature that looks biological actually is. One of the Working Group’s key concerns is avoiding false positives—non-living materials that mimic biological signatures.

For example, iron oxide (rust) creates a “red slope” in reflectance that can resemble the vegetation red edge when observed at low resolution. Mars, rich in iron oxides, is a perfect example of how misleading this can be.

Other problematic materials include cinnabar (mercury sulfide), which has a sharp reflectance edge around 600 nanometers, and elemental sulfur, which produces an edge between 450 and 500 nanometers. With insufficient resolution, combinations of these materials could be mistaken for life.

This is why the paper repeatedly emphasizes the need for high-resolution spectroscopy across a broad wavelength range. Distinguishing a forest-covered planet from a mineral-rich but lifeless world depends on it.

Why Earth’s History Matters for Exoplanet Science

One of the most important ideas behind this research is that life does not have a single appearance. Earth itself has gone through multiple biological phases, each with its own surface colors and spectral signatures.

By studying Earth’s past, scientists can expand the search for life beyond modern, plant-covered worlds. Planets dominated by purple microbes or green oceans may be just as alive, even if they look nothing like present-day Earth.

The Budget Reality

As ambitious as these goals are, the paper acknowledges a sobering reality. Building a telescope with this level of sensitivity and spectral coverage is expensive. With recent cuts to major NASA programs, it remains uncertain how much of the Working Group’s vision will survive the budgeting process.

Still, the researchers argue that without these capabilities, HWO risks missing some of the most compelling signs of life the universe might offer.

A Broader Look at Surface Biosignatures

Surface biosignatures are increasingly seen as a critical complement to atmospheric ones like oxygen or methane. While atmospheric gases can hint at life, surface features provide context, helping scientists rule out geological explanations and better understand a planet as a complete system.

If HWO succeeds, it could tell us whether distant worlds host green oceans, purple microbial mats, lush forests, or something entirely unexpected.

Research paper:

Parenteau et al., Habitable Worlds Observatory Living Worlds Working Group: Surface Biosignatures on Potentially Habitable Exoplanets, arXiv (2026)

https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.08883