Searching for Wandering Black Holes in Dwarf Galaxies Reveals Confirmations, Imposters, and New Mysteries

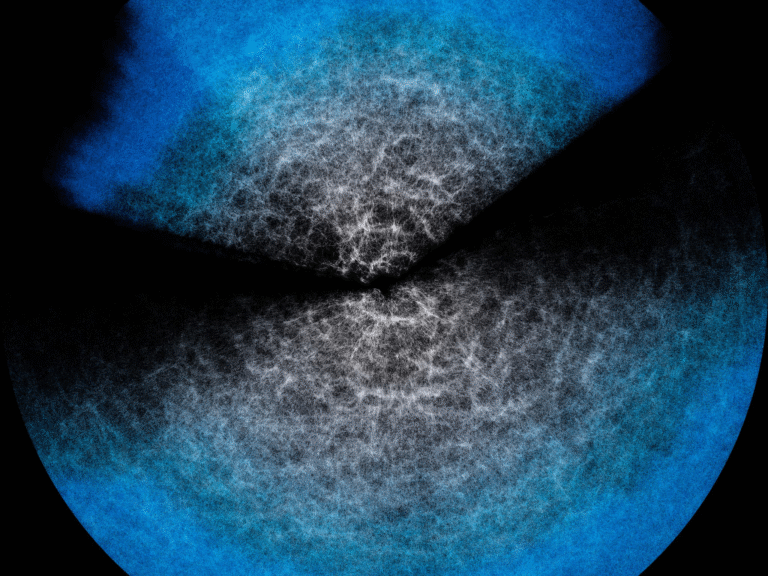

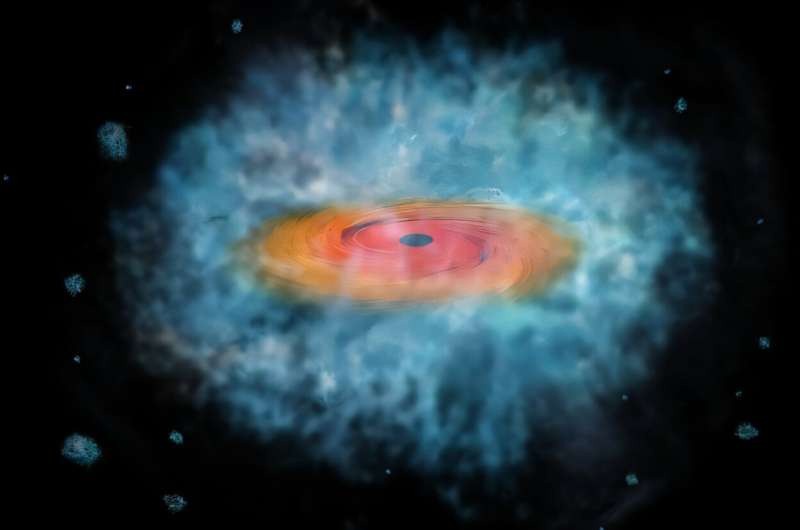

Astronomers have long suspected that dwarf galaxies—the smaller, less-evolved galaxies scattered throughout the universe—might host massive black holes that don’t sit neatly at their centers. These so-called wandering black holes could hold important clues about how the earliest black holes formed and how galaxies grew around them. A new study led by Megan R. Sturm of Montana State University adds crucial pieces to this puzzle by taking a closer look at 12 potential candidates using data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope. The results reveal confirmed black holes, mistaken identities, and several enigmatic sources that remain unresolved.

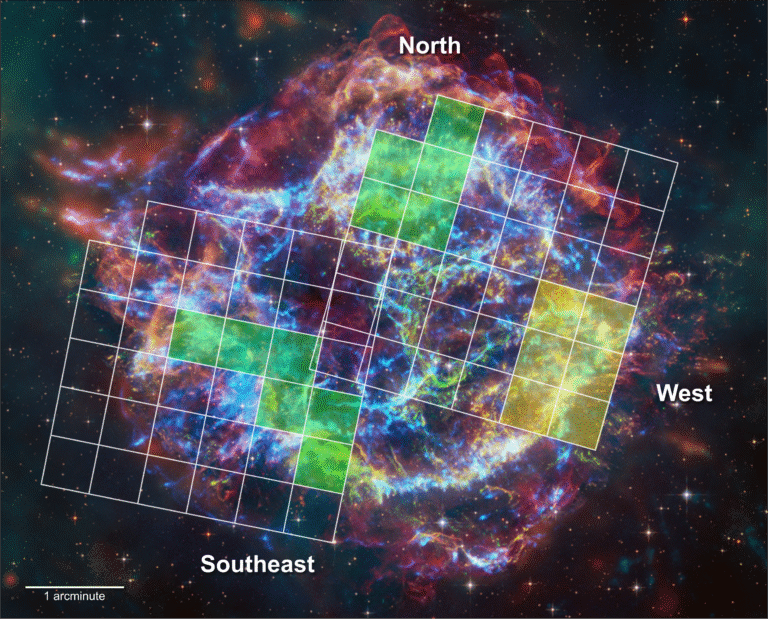

This new work builds on earlier observations by the Very Large Array (VLA), which found 111 dwarf galaxies with intriguing radio signals. From that list, researchers singled out 12 galaxies whose compact radio emissions resembled the kind produced by accreting black holes. But radio data alone isn’t enough to confirm the presence of a black hole. Other astrophysical processes—especially intense star formation—can mimic those radio signatures. That’s why the team turned to multi-wavelength observations to gather firmer evidence.

What the Researchers Confirmed

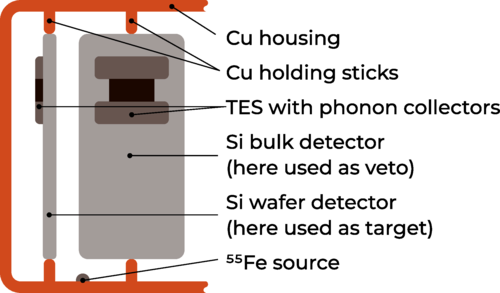

Out of the 12 radio-selected candidates, the team confidently confirmed three as hosting active black holes. This confirmation required the presence of radio, X-ray, and optical signatures consistent with accretion—the process where material spirals into a black hole, heating up and emitting radiation in several wavelengths.

One of these, catalogued as ID 26, stood out because it was the only candidate bright across all three wavelengths. That makes it a particularly strong and straightforward case of an active black hole.

Another confirmed black hole, ID 82, was much more noticeable in X-rays than in optical light. The researchers suggest that thick layers of gas and dust likely obscure its optical emission. Interestingly, previous studies had reported coronal emission lines for this same object, strengthening the case that it truly is an accreting black hole.

The third confirmed candidate, ID 83, showed strong X-ray brightness and optical features consistent with black hole activity, even if its radio signal wasn’t exceptional. Together, these three objects give astronomers reliable examples of black holes in dwarf galaxies—and a better baseline for identifying future candidates.

The Imposters in the Sample

Two of the 12 radio sources turned out not to be black holes at all.

The first misidentified source, ID 64, initially appeared promising because its optical emission was bright and clearly offset from the galaxy’s center, a potential sign of a wandering black hole. But when the team checked the redshifts—a measurement related to distance—they discovered something surprising: the optical light didn’t belong to the dwarf galaxy they were studying. Instead, it came from a background galaxy whose own active nucleus just happened to line up with the foreground dwarf galaxy. In other words, it was a cosmic coincidence, not a wandering black hole.

The second imposter, ID 92, was exposed through Hubble’s high-resolution imaging. It showed that the radio source aligned with a particularly vigorous star-forming region. Further analysis suggested that the radio emission likely came from a super star cluster, not an active galactic nucleus. Star-forming regions can produce strong radio signals thanks to supernova remnants and massive young stars, making them easy to confuse with black holes unless multiple wavelengths are examined.

Seven Candidates With No Clear Identity

After the confirmed black holes and the imposters, seven sources remained. These radio signals showed no detectable X-ray or optical emissions, leaving their identities unresolved. Multi-wavelength non-detections can happen for several reasons:

- The radio sources might be background objects unrelated to the dwarf galaxies.

- They might be extremely faint accreting black holes below the detection limits of current telescopes.

- They might be non-AGN astrophysical sources like embedded star clusters.

- Their black holes (if present) might be shrouded in dust or too small to produce detectable radiation.

The authors propose that three of these seven are likely background galaxies because they sit far from the centers of their supposed host dwarfs—much farther than simulations predict for wandering black holes.

One particularly intriguing unresolved candidate is ID 65, whose radio characteristics suggest it could even be related to a fast radio burst (FRB). FRBs are powerful but mysterious radio pulses, and their origins are still debated. While this idea is speculative, it highlights how unexpected discoveries often emerge from ambiguous data.

Why Wandering Black Holes Matter

Understanding wandering black holes in dwarf galaxies is not just an exercise in curiosity—it has major implications for cosmic history.

One possibility is that early black holes formed inside dense gas clouds rather than at the centers of young galaxies. If so, dwarf galaxies might still retain these off-center relics because they undergo fewer mergers and less disruption. These black holes could represent the closest analogs to the universe’s first black hole “seeds.”

Simulations also suggest that up to 50% of central black holes in dwarf galaxies could be displaced due to shallow gravitational potentials. Even a small gravitational “kick,” from a merger or asymmetric gravitational waves, can nudge a black hole far from the center—sometimes so far that it never settles back into place.

Moreover, many galaxies grow by merging with others. In larger galaxies, this process erases the early history. But dwarf galaxies are simpler systems with less violent pasts, making them valuable time capsules of black hole evolution.

What Comes Next for These Mysterious Objects

The study’s limitations point toward future opportunities. The non-detections don’t necessarily mean the absence of black holes—just that the current instruments couldn’t confirm them. Observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) could provide the deeper infrared sensitivity needed to detect objects hidden behind dust or with faint optical signatures.

The authors note that JWST’s fifth-year observing time selections are approaching, but it’s unclear whether proposals targeting these specific sources were submitted.

Even without new data, this study marks a significant step forward. It shows how challenging it is to classify black hole candidates in dwarf galaxies and emphasizes the need for multi-wavelength astronomy to distinguish real wanderers from imposters.

A Broader Look at Black Holes in Dwarf Galaxies

Beyond this specific research, wandering black holes in dwarf galaxies are becoming a growing area of interest. Additional studies—such as the recent identification of a promising candidate with a parsec-scale jet and decades-long radio variability—suggest that these objects may be more common than previously believed.

Dwarf galaxies therefore may hold key answers to some of astronomy’s biggest questions:

- How did the earliest black holes in the universe form?

- Did black holes grow first, or did galaxies grow first?

- How often do black holes drift away from galaxy centers?

- How many black holes are we missing because we only search galactic nuclei?

As more observations come in, astronomers hope to build a clearer picture of how widespread wandering black holes truly are.

Research Paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.09641