Simultaneous Packing Structures in Superionic Water May Explain the Strange Magnetic Fields of Ice Giants

Superionic water is one of the strangest forms of matter scientists know. It is not liquid water, not ordinary ice, and not quite something in between. Instead, it is a hot, dense, black, and electrically conductive form of ice that exists only under extreme pressures and temperatures—conditions found deep inside planets like Neptune and Uranus. First predicted back in the 1980s and experimentally created in a laboratory in 2018, superionic water has continued to surprise researchers. Now, a new study suggests it may be even more complex than previously thought.

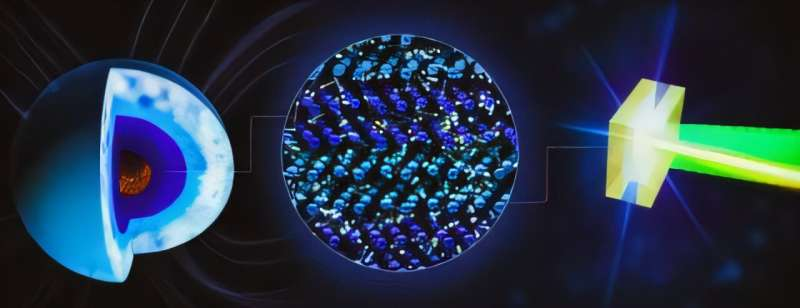

In research published in Nature Communications, scientists have discovered that multiple atomic packing structures can exist at the same time within superionic water, even under identical temperature and pressure conditions. This unexpected behavior may help explain why ice giant planets have such unusual and chaotic magnetic fields, unlike anything seen on Earth.

What Makes Superionic Water So Unusual?

Under normal conditions, water behaves in familiar ways: it freezes into ice, melts into liquid, or evaporates into vapor. But under the extreme pressures of millions of atmospheres and temperatures of thousands of degrees, water transforms into something exotic.

In superionic water, the oxygen atoms lock themselves into a rigid crystalline lattice, similar to a solid. At the same time, hydrogen ions move freely through that lattice, flowing almost like electrons in a metal. This combination gives superionic water its high electrical conductivity, a property that is crucial when thinking about planetary magnetic fields.

This strange dual behavior—solid oxygen and fluid hydrogen—sets superionic water apart from almost all other known phases of matter.

A Clue to the Magnetic Mysteries of Uranus and Neptune

When NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft flew past Uranus and Neptune in the late 1980s, scientists were baffled. Unlike Earth, Jupiter, or Saturn, whose magnetic fields are relatively smooth and aligned with their rotation axes, the ice giants showed lumpy, tilted, and highly complex magnetic fields with multiple poles.

Today, scientists believe the answer lies deep inside these planets. While Earth’s magnetic field is generated by molten iron moving in its outer core, Uranus and Neptune likely rely on electrically conductive superionic water in their interiors. The way this material conducts electricity could strongly influence how their magnetic fields form and behave.

Mapping the Phases of Superionic Water

The goal of the new study was to better understand the phase diagram of superionic water. A phase diagram shows how a substance changes structure as temperature and pressure vary. Instead of focusing on solid, liquid, and gas states, the researchers examined how oxygen atoms pack together inside superionic water.

Earlier models suggested that oxygen atoms would transition cleanly from one crystalline structure to another as pressure increased. The main structures of interest were:

- Body-centered cubic (BCC), with about 68% packing efficiency

- Face-centered cubic (FCC), with about 74% efficiency

- Hexagonal close-packed (HCP), also around 74% efficiency

Under normal circumstances, materials shift sharply from one structure to another at specific conditions. The researchers expected to see clear boundaries between these phases.

That is not what happened.

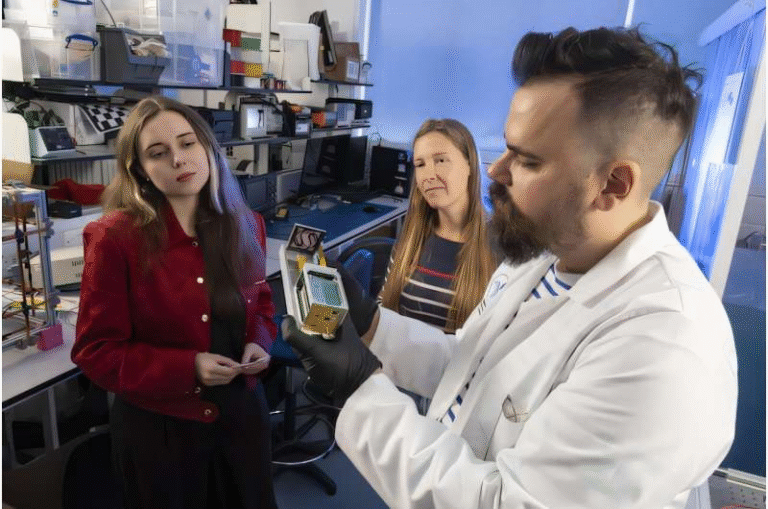

Recreating Planetary Interiors in the Lab

Studying superionic water is exceptionally difficult. Researchers must generate extreme pressures and temperatures inside a vacuum and capture data within fractions of a second before the sample destabilizes.

To do this, the team used the Matter in Extreme Conditions (MEC) instrument at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. They later repeated the experiments at the European XFEL using its High Energy Density instrument to confirm the results.

Laser-driven shock waves compressed water samples to immense pressures, while additional lasers raised temperatures to planetary interior levels. Ultrafast X-ray diffraction allowed the scientists to observe how oxygen atoms arranged themselves over time, with astonishing precision.

A Surprising Discovery: Blurred Phase Boundaries

Instead of neat transitions between crystal structures, the data revealed something unexpected. The researchers consistently observed multiple packing structures coexisting simultaneously under the same conditions.

In some experiments, BCC and FCC structures appeared together. In others, FCC and HCP structures overlapped, forming what scientists describe as a mixed close-packed structure. Rather than separating cleanly into different phases, superionic water showed blurred boundaries, with different atomic arrangements stacked throughout the material.

To rule out experimental error, the team repeated the study at a second XFEL facility. The results were the same.

This kind of behavior is extremely rare. Almost all known materials show clear phase transitions. Superionic water appears to break that rule.

Why Mixed Structures Matter

The electrical conductivity of superionic water depends heavily on the arrangement of its oxygen lattice. Because hydrogen ions move through this lattice, even subtle changes in atomic structure can affect how easily electrical currents flow.

At the scale of a planet, these small differences may translate into dramatically different magnetic field patterns. A mixed or disordered lattice could help explain why Uranus and Neptune generate magnetic fields that are irregular, offset, and far from symmetrical.

Understanding these structures is therefore not just a materials science problem—it is a planetary physics problem with implications across astronomy.

Why Ice Giants Matter Beyond Our Solar System

Although only two of the eight planets in our solar system are ice giants, planets of this type appear to be common throughout the observable universe. Many exoplanets fall into size and composition ranges similar to Uranus and Neptune.

By learning how superionic water behaves, scientists gain insight into:

- How ice giant planets form

- How their interiors evolve over time

- How magnetic fields shape planetary atmospheres and radiation environments

These factors are critical for understanding planetary systems far beyond our own.

Superionic Water and Extreme Matter Physics

Beyond astronomy, this research has broader importance in high-pressure physics. Superionic water challenges traditional ideas about phase transitions and crystalline order. It also provides a natural example of a fast ion conductor, a class of materials that interests researchers studying energy storage and transport under extreme conditions.

While superionic water itself cannot exist on Earth outside specialized experiments, the physics it reveals may inspire new theoretical models and laboratory materials.

What Comes Next?

The researchers plan to integrate these findings into advanced computer simulations to better understand why superionic water behaves this way. Future experiments aim to directly measure how electrical conductivity changes with different packing structures and to test more realistic chemical mixtures, such as water combined with other compounds expected inside planetary interiors.

Each step brings scientists closer to understanding how microscopic atomic arrangements can shape the magnetic personality of entire planets.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67063-2