Space Mice Come Home and Start Families After Returning From Orbit

Four mice went to space aboard China’s space station, lived in microgravity for two weeks, and returned safely to Earth. That alone would be a neat science headline. But what happened next is what really caught scientists’ attention. One of the female mice later became a mother, giving birth to nine healthy pups, offering an important clue about whether mammals can reproduce normally after spaceflight.

This experiment may sound small, but its implications stretch far beyond mice. It touches on one of the biggest unanswered questions about long-term space exploration: can life continue normally beyond Earth?

The Shenzhou-21 Mouse Mission Explained

On 31 October, China launched the Shenzhou-21 spacecraft to its space station, orbiting about 400 kilometers above Earth. On board were four mice, identified by the numbers 6, 98, 154, and 186. These rodents became China’s first mice to participate in an orbital life-science experiment.

For 14 days, the mice lived in microgravity. During that time, they were exposed to space radiation, weightlessness, and the unusual conditions of orbital life. Scientists were interested in how these factors might affect basic mammalian biology, especially reproduction and long-term health.

The spacecraft returned to Earth on 14 November, bringing the mice back safely. At that point, the mission appeared successful. But the most interesting result was still weeks away.

A Birth That Caught Scientists’ Attention

On 10 December, one of the female mice gave birth to nine pups. Of those, six survived, which researchers say falls within the normal survival range for laboratory mice. The mother was nursing properly, and the pups were active and developing as expected.

This was significant because, until now, evidence around mammalian reproduction and spaceflight has been limited. Previous studies had shown that sperm from space-exposed mice could be used to fertilize eggs back on Earth. However, seeing a female mouse return from space, conceive naturally, and give birth successfully adds a new layer of confidence.

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Zoology emphasized that short-term spaceflight did not appear to damage the mouse’s reproductive ability. That may sound like a narrow finding, but it carries broader implications.

Why Mice Matter So Much in Space Research

Mice are not chosen for space experiments by accident. They share a high degree of genetic similarity with humans, reproduce quickly, and show physiological responses to stress that often mirror human biology.

If something fundamental about mammalian reproduction were disrupted by space conditions, mice would likely show it first. Their short life cycles also make it possible to study multi-generational effects, something that would take decades in human populations.

In other words, mice act as an early warning system. If reproduction works for them after space exposure, that is cautiously encouraging news for future human missions.

Life Aboard the Space Station for the Mice

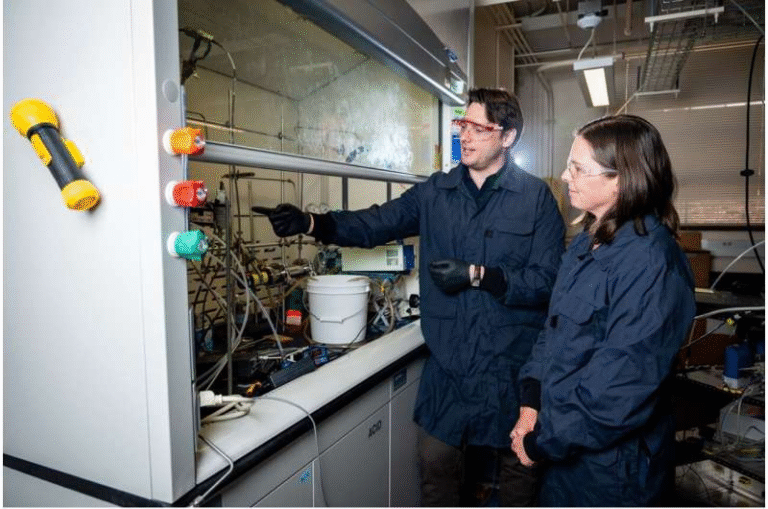

The mice lived in a specially designed rodent habitat aboard the space station. Conditions were carefully controlled to reduce unnecessary stress and maintain biological rhythms similar to those on Earth.

Lights turned on at 7 a.m. and off at 7 p.m., preserving an Earth-like circadian cycle. Their food was nutritionally balanced and intentionally hard, allowing the mice to grind their teeth as they naturally do. Directional airflow helped keep the habitat clean by pulling hair and waste into collection containers.

An AI-based monitoring system tracked the mice’s movements, sleep cycles, and eating patterns in real time. This system wasn’t just for observation. It helped researchers predict when food and water supplies might run low.

An Unexpected Challenge in Orbit

The mission did not go entirely according to plan. When the return schedule for Shenzhou-20 changed unexpectedly, the mice faced a longer stay in orbit than originally planned. This raised concerns about a possible food shortage.

The ground team reacted quickly. They tested several emergency food options from the astronauts’ own supplies, including compressed biscuits, corn, hazelnuts, and soy milk. These foods were tested on Earth first to ensure they would be safe for the mice.

After evaluation, soy milk was selected as the safest emergency option. Water was pumped into the habitat through an external port, while the AI monitoring system helped track consumption and estimate how long supplies would last.

This improvisation highlighted how even small biological experiments in space require constant adaptation and close monitoring.

Monitoring the “Space Pups”

The story does not end with the birth of the pups. Researchers are now closely tracking their growth curves, physical development, and overall health. They are looking for any subtle physiological changes that might suggest hidden effects from their mother’s time in space.

One of the most important next steps is determining whether these pups can reproduce normally themselves. That would help scientists understand whether space exposure has any multi-generational consequences, especially those that might not show up immediately.

So far, the early signs are encouraging, but researchers are careful not to draw sweeping conclusions from a single case.

What This Means for Human Spaceflight

Before humans attempt years-long missions to Mars or establish permanent settlements on the Moon, scientists need answers to some uncomfortable questions. Can mammals conceive, gestate, and give birth normally after space exposure? Does radiation damage eggs or sperm in ways that only appear in the next generation?

One mouse giving birth does not solve these problems. But it is a promising data point, especially when combined with earlier studies involving space-exposed sperm and embryos.

This experiment adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that short-term spaceflight may not fundamentally disrupt mammalian reproduction. That is an encouraging signal for long-term exploration, even if many questions remain unanswered.

How This Fits Into Global Space Biology Research

China is not alone in studying rodents in space. NASA and other space agencies have conducted similar experiments aboard the International Space Station, focusing on bone density loss, muscle atrophy, immune system changes, and genetic expression.

What makes this experiment stand out is its focus on post-flight reproduction, rather than just survival or short-term physiological changes. It shifts attention from how bodies cope in space to whether life itself can continue normally afterward.

As space agencies around the world plan longer missions, this kind of research is becoming increasingly important.

A Small Experiment With Big Questions

At first glance, this might seem like a niche scientific result. But the birth of six healthy “space pups” after orbital exposure speaks directly to humanity’s future beyond Earth.

It does not guarantee that reproduction will be easy or safe in space. But it does suggest that space does not immediately break one of the most fundamental processes of life.

For now, researchers will keep watching these mice, collecting data, and asking careful questions. And for anyone interested in the future of space exploration, this quiet little experiment is worth paying attention to.

Research reference:

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Zoology – official research report and updates on the Shenzhou-21 rodent experiment

https://www.cas.cn/cm/202512/t20251229_5094450.shtml