Stars and Planets Are Linked Together and Dust Is the Key to Understanding How They Form, Evolve, and Die

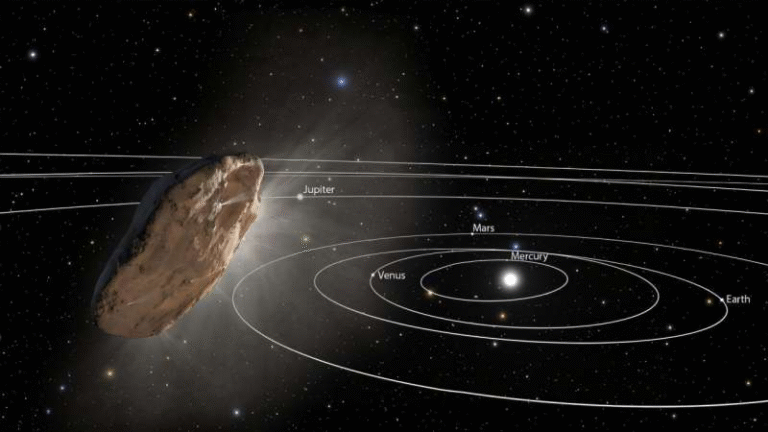

Stars and planets are not separate actors playing independent roles in the universe. They are deeply connected, forming together and influencing each other throughout their entire lifetimes. A growing body of research shows that if we want to truly understand how planets like Earth came into existence—and how they may ultimately meet their end—we must also understand the life cycles of stars. At the heart of this connection lies something that might sound unassuming but is absolutely critical: dust.

A recent white paper titled Bridging stellar evolution and planet formation: from birth, to survivors of the fittest, to the second generation of planets explores this relationship in detail. Submitted to the European Southern Observatory’s Expanding Horizons initiative, the paper is led by Akke Corporaal of the European Southern Observatory and is available on the arXiv preprint server. The authors argue that stars and planets form, live, and evolve together, with dust playing a central role at every stage.

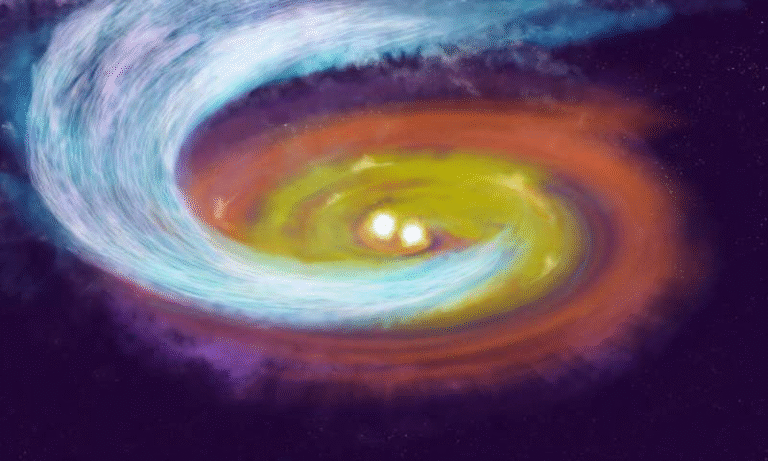

Stars and planets form together in dusty environments

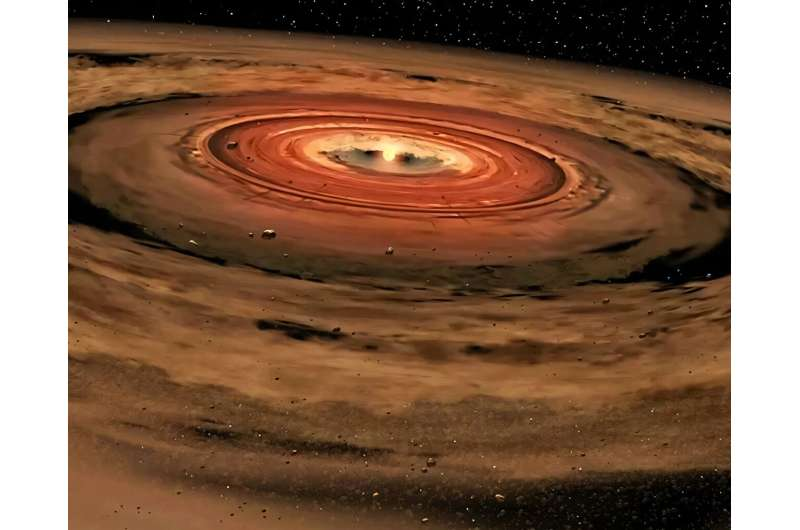

Planet formation begins inside protoplanetary disks, which are vast, rotating disks of gas and dust surrounding young stars. These disks are created during the birth of a star, meaning that planets do not appear as an afterthought. Instead, they emerge as a natural byproduct of stellar formation.

Dust grains within these disks collide, stick together, and slowly grow in size. Over time, they can become pebbles, rocks, planetesimals, and eventually full-fledged planets. The star at the center of the disk shapes this process by providing energy, radiation, and gravity, while the dust controls how material cools, clumps, and moves.

This tight connection means that understanding planet formation requires understanding stellar evolution as well. The paper emphasizes that stars shape the fate of their planets not only at birth, but throughout their lives—and even in death.

Dust as the missing link in planet formation

Dust is far more than leftover debris. It is a dynamic and influential component of planetary systems. In protoplanetary disks, dust grains are responsible for absorbing ultraviolet and visible light from the star and re-emitting it as infrared radiation. This process regulates the disk’s temperature and structure, effectively acting as a thermostat.

As dust grains grow larger, their physical and thermal properties change. Larger grains absorb and emit radiation differently, which can shift the location of frost lines—regions in the disk where specific molecules such as water, carbon dioxide, or methane freeze into ice. These frost lines strongly influence what types of planets can form and where they can form. Gas giants, icy worlds, and rocky planets are all shaped by these subtle dust-driven temperature changes.

Dust grains also serve as chemical factories. Water and complex organic molecules form on their surfaces, eventually becoming incorporated into planets. This makes dust a key ingredient not just for planet formation, but for the emergence of potentially habitable worlds.

The pebble problem and dust dynamics

One of the major unsolved problems in planet formation is what happens when dust grains grow to pebble size. At this stage, the grains experience strong gas drag from the disk, causing them to spiral inward toward the star in a process known as radial drift. Without a way to overcome this effect, many growing planets would be lost before they ever fully form.

The paper highlights that pebbles can survive if they clump together in regions of high pressure within the disk. These pressure traps allow pebbles to resist gas drag and continue growing. However, the exact mechanisms behind this process remain poorly understood because they occur on extremely small spatial scales that current telescopes cannot resolve.

Mapping dust motion and grain growth close to stars is therefore essential. According to the authors, resolving these inner regions is critical for advancing our understanding of both stellar and planetary evolution.

What happens when stars grow old

Dust does not stop being important once planets form. As stars age and leave the main sequence, they enter phases such as the red giant branch (RGB) and asymptotic giant branch (AGB). During these stages, stars swell dramatically and produce powerful stellar winds that expel large amounts of material into space.

These winds can create new dusty disks around evolved stars. The paper explores the possibility that these disks might give rise to second-generation planets, forming long after the original planetary system was established. In other cases, existing planets may be reshaped, engulfed, or ejected as their host star evolves.

The authors point out that we still lack a clear understanding of how planetary systems transition through the RGB, AGB, and post-RGB/AGB phases. Linking these late stages to earlier planet formation processes is one of the major open challenges in astronomy.

What modern telescopes have revealed so far

Astronomy has made remarkable progress in recent decades. Facilities like ALMA have provided detailed images of dozens of protoplanetary disks, revealing gaps, rings, and asymmetries that hint at ongoing planet formation. The James Webb Space Telescope has taken this even further by using infrared light to peer through dust and uncover fine structures such as spiral arms within disks.

Despite these advances, major gaps remain. Even the most powerful current and planned telescopes cannot resolve dust processing at the scales required to fully understand planet formation and evolution across the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram, which charts stellar lifecycles.

Key processes like dust clumping, grain growth, and planet–disk interactions remain hidden from view, particularly in the innermost regions of disks within 10 astronomical units of the star.

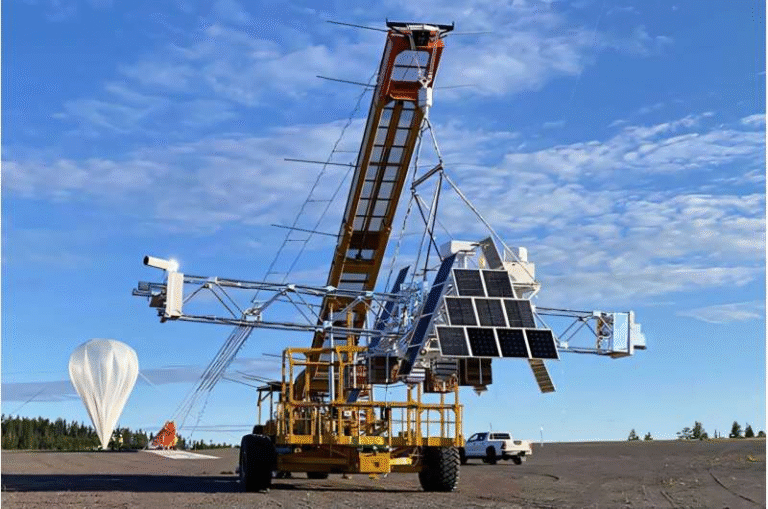

The case for a next-generation infrared interferometer

To overcome these limitations, the authors propose the development of a near-infrared to mid-infrared interferometer with an angular resolution of about 0.1 milliarcseconds. For comparison, the James Webb Space Telescope has a resolution of about 0.07 arcseconds, making this proposed instrument dramatically sharper.

Such an interferometer would surpass the capabilities of existing arrays like VLTI and CHARA, allowing astronomers to directly image dusty structures at sub-au scales. This would make it possible to study the very inner regions of planet-forming disks and evolved stellar disks in unprecedented detail.

The paper outlines a long-term observational roadmap. During the 2030s, facilities like the Extremely Large Telescope and the Very Large Telescope could focus on detecting close-in exoplanets embedded in dusty environments. During the 2040s, the proposed interferometer would push even deeper, revealing structures that are currently completely inaccessible.

Why this research matters

This white paper does more than outline technical challenges. It calls for a shift in how astronomers think about stars and planets—not as separate fields of study, but as interconnected parts of a single evolutionary story.

By placing dust physics at the center of this narrative, the authors argue that we can better understand how solar systems form, survive, and sometimes regenerate. This knowledge does not only apply to distant exoplanets. It also helps us understand the past and future of our own solar system, including what may happen to Earth when the Sun eventually leaves the main sequence.

There are still many unanswered questions, especially regarding how dusty disks and planetary systems behave during the late stages of stellar evolution. But with the right observational tools, the coming decades could provide the answers needed to connect the full life cycles of stars and planets into a single, coherent picture.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.17976