The Ambitious Plan to Spot Habitable Moons Around Giant Planets

So far, astronomers have confirmed thousands of planets orbiting other stars, yet one important class of objects remains frustratingly elusive: exomoons. These are moons that orbit exoplanets, and despite years of searching, none have been definitively confirmed. According to a new research paper by Thomas O. Winterhalder of the European Southern Observatory and his collaborators, this absence does not mean exomoons are rare or nonexistent. Instead, the problem is much simpler and far more technical — we do not yet have the right tools to see them.

The study, published as a preprint on arXiv, outlines a bold and technically demanding solution: a kilometric baseline interferometer capable of detecting Earth-sized moons orbiting giant planets up to 200 parsecs, or about 652 light-years, away. If built, this instrument could fundamentally change how we search for potentially habitable worlds beyond our solar system.

Why We Still Haven’t Found an Exomoon

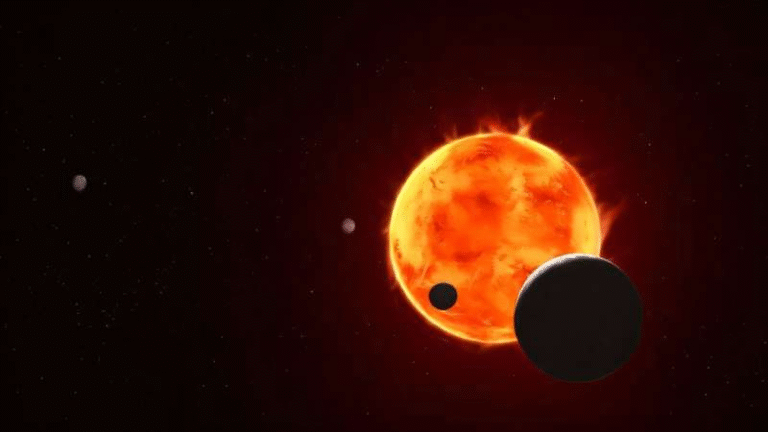

Astronomers have tried hard to find exomoons, mostly using the transit method. This technique looks for tiny dips in a star’s brightness when a planet passes in front of it. In principle, a moon could also create a detectable dip. In practice, this method is extremely unforgiving when applied to moons.

To successfully detect an exomoon using transits, the alignment has to be nearly perfect. Earth, the star, the planet, and the moon must all line up in just the right way. Even small deviations can erase the signal entirely. While planets are large enough to produce noticeable dips in starlight, moons are much smaller and their signals are easily lost in noise.

There is another complication. The transit method works best for planets that orbit very close to their stars. However, planets that migrate too close to their stars struggle to hold onto moons. This is because a planet’s Hill sphere — the region where its gravity dominates and allows moons to remain bound — shrinks as the planet gets closer to its star. In short, the planets most favorable for transit detection are least likely to have moons at all.

Astrometry as a Better Path Forward

The new paper argues that astrometry offers a far more promising route. Astrometry measures the precise position of an object in the sky and tracks how that position changes over time. Traditionally, this technique has been used to detect planets by observing the tiny wobble they induce in their host stars.

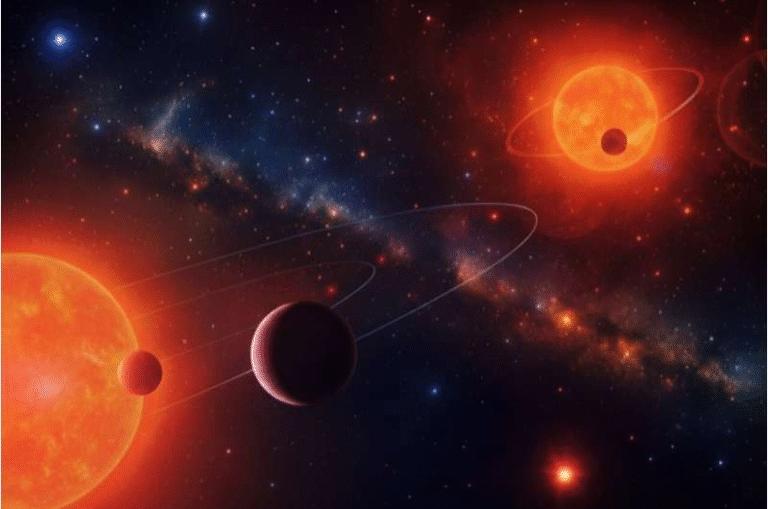

For exomoons, the logic flips. Instead of watching stars, astronomers would watch planets themselves. A moon orbiting a planet causes the planet to wobble around a shared center of mass. Detecting that motion could reveal the moon’s presence, its mass, and its orbital distance.

Astrometry is especially well suited for planets that orbit far from their stars, exactly the kind of systems where moons are more likely to survive. The challenge is precision.

Why Current Telescopes Fall Short

At present, the most advanced optical interferometer available is the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) in Chile. It combines light from four large telescopes spread across a baseline of about 200 meters. Even with this setup, VLTI can only resolve positional changes of around 50 microarcseconds (µas).

According to Winterhalder and his team, this level of precision is nowhere near sufficient. To detect Earth-sized moons around Jupiter-like planets at distances of up to 200 parsecs, astronomers would need accuracy closer to 1 microarcsecond. That is roughly 50 times more precise than what VLTI can achieve.

Reaching that level of resolution requires a dramatic increase in baseline length. The proposed interferometer would stretch across several kilometers, hence the name kilometric baseline interferometer. In interferometry, resolution improves as the baseline increases, because resolution depends on the observed wavelength divided by the distance between mirrors.

Learning From Gravitational Wave Observatories

The concept may sound extreme, but it is not without precedent. Interferometry has already proven its power through facilities like the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which detected gravitational waves using kilometer-scale baselines. While LIGO uses lasers in vacuum tunnels rather than mirrors collecting starlight, the underlying physics is similar.

The proposed exomoon interferometer would combine light from multiple widely spaced telescopes to achieve unprecedented angular resolution. Technically, this is challenging but not impossible with future advancements in optics, stability, and data processing.

Working Alongside the Extremely Large Telescope

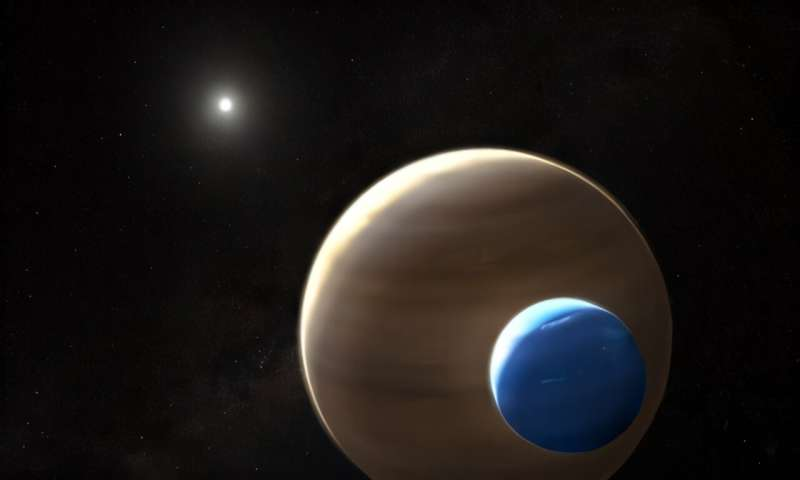

One of the most compelling aspects of the proposal is how well it complements upcoming observatories, particularly the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT). Currently under construction, the ELT will feature a 39-meter primary mirror, making it the largest optical telescope ever built.

The ELT will excel at directly imaging faint, distant exoplanets, especially giant planets orbiting far from their stars. Once such planets are identified, the kilometric interferometer could then monitor them over time to look for the subtle wobble caused by orbiting moons.

Together, these instruments would form a powerful one-two punch: find the planet first, then search for its moons.

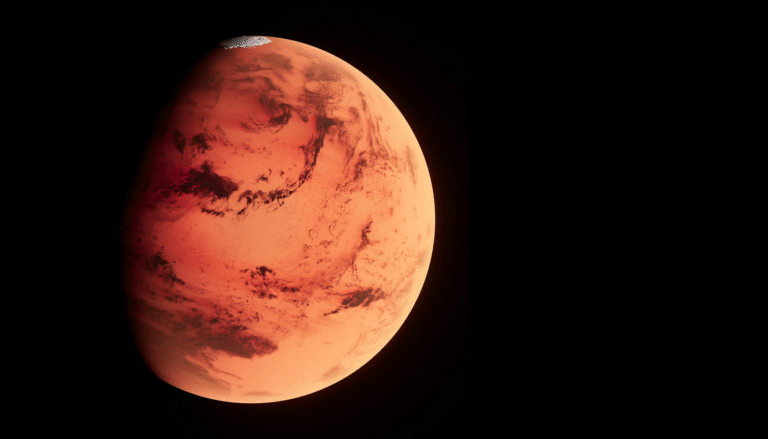

Why Exomoons Could Be Habitable

One of the most exciting implications of this work is its relevance to habitability. When people think of habitable worlds, they often imagine Earth-like planets sitting comfortably in the so-called Goldilocks zone around their stars. Moons, however, play by different rules.

In our own solar system, moons like Europa and Enceladus are considered strong candidates for hosting life, despite being far from the Sun. Their potential habitability comes not from sunlight, but from tidal heating. Gravitational interactions with their giant planet hosts generate internal heat, keeping subsurface oceans liquid beneath icy shells.

The paper suggests that similar processes could operate in other planetary systems. Large moons orbiting gas giants may remain warm and geologically active even if they are far from their stars. This makes them intriguing targets in the search for life beyond Earth.

Limits of the Proposed Technology

Despite its promise, the proposed interferometer would not be able to detect moons as small as Europa or Enceladus. These moons are significantly smaller than Earth, falling below even the ambitious detection threshold described in the paper.

However, the researchers argue that larger versions of such moons may exist elsewhere in the galaxy. Detecting even one large, potentially habitable exomoon would be a landmark discovery, opening a new chapter in exoplanet science.

Cost, Timing, and the Road Ahead

Building a kilometric baseline interferometer would not be cheap. While the paper does not provide detailed financial estimates, the authors suggest the cost would likely run into several billion dollars, comparable to the price of the ELT itself.

There is currently no confirmed funding or construction timeline for the project. However, the idea could gain traction once the ELT becomes operational, which is expected around 2028. At that point, the astronomical community may see this interferometer as a logical next step.

For now, the project remains a vision — ambitious, technically demanding, and scientifically compelling. If realized, it could finally allow astronomers to detect the first confirmed exomoon and potentially identify the first habitable world that is not a planet.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.15858