The Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS Is Finally Revealing What Alien Comets Are Made Of

When the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS swept past the Sun in late October 2025, astronomers knew they were looking at something special. This icy visitor became only the third confirmed object from outside our solar system ever detected, following the enigmatic ʻOumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019. Unlike its predecessors, however, 3I/ATLAS arrived at just the right time and in just the right way to allow scientists to study it in remarkable detail. As a result, it is now offering the clearest picture yet of what comets from other star systems may actually be like.

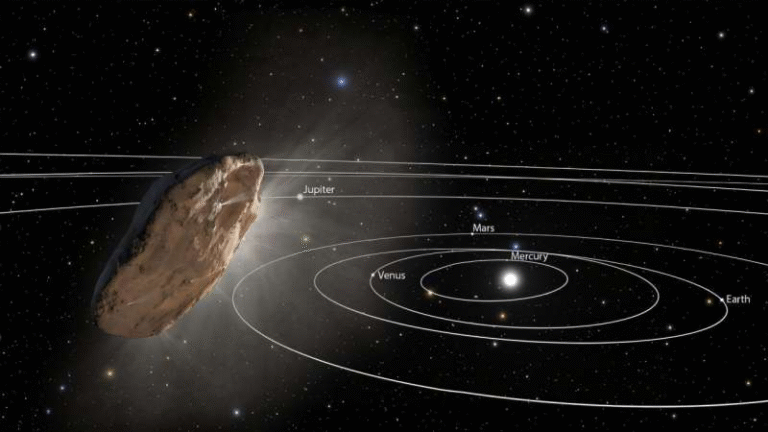

A Rare Visitor From Beyond the Solar System

Interstellar objects are incredibly difficult to spot. They move fast, appear with little warning, and often pass through the inner solar system before telescopes can be properly aimed at them. 3I/ATLAS, discovered by the ATLAS survey in mid-2025, followed a strongly hyperbolic trajectory, confirming that it was not gravitationally bound to the Sun. In simple terms, it came from another star system and will eventually head back into interstellar space.

What immediately set this object apart was its timing and brightness. Unlike ʻOumuamua, which showed almost no visible gas or dust, and even 2I/Borisov, which was detected relatively late, 3I/ATLAS was observed extensively both before and after perihelion, its closest approach to the Sun on 30 October 2025.

An Unexpected Helper: SOHO’s SWAN Instrument

One of the most valuable data sets on 3I/ATLAS came from an unexpected source. The Solar and Heliosphere Observatory (SOHO) has been studying the Sun for nearly three decades from a position about 1.5 million kilometers from Earth. While most of SOHO’s instruments focus directly on solar activity, one camera onboard, called SWAN (Solar Wind Anisotropies), has a different purpose.

SWAN is designed to detect a specific wavelength of ultraviolet light emitted by hydrogen atoms, allowing it to create an all-sky map of hydrogen scattered throughout the solar system. This capability makes it uniquely suited to studying comets, because when sunlight breaks apart water molecules released by a comet, hydrogen atoms are produced and begin to glow in ultraviolet light.

Measuring Water From an Alien Comet

Nine days after 3I/ATLAS passed perihelion, SWAN detected a clear hydrogen glow surrounding the comet. This signal allowed astronomers to calculate how much water the comet was releasing into space. The results, later published on the arXiv preprint server, were striking.

On 6 November 2025, when the comet was about 1.4 astronomical units from the Sun, it was producing water at a rate of 3.17 × 10²⁹ molecules per second. That number is difficult to visualize, but it corresponds to filling something like an Olympic-sized swimming pool every few seconds. For a comet with a relatively small nucleus, this is an enormous amount of activity.

Over the following weeks, the water production steadily declined. By early December, roughly 40 days after perihelion, the rate had dropped to between 10 and 20 trillion molecules per second. This gradual decrease is exactly what astronomers expect as a comet moves farther from the Sun and receives less heat.

Why Post-Perihelion Observations Matter

Most observations of 3I/ATLAS were made before perihelion, while the comet was still heating up. The SWAN data are particularly valuable because they captured what happened after the closest solar encounter. This phase is critical for understanding how cometary activity winds down and whether interstellar comets behave differently from those formed in our own solar system.

So far, 3I/ATLAS appears to follow a very familiar pattern. As solar heating decreases, ice sublimation slows, and activity fades. This suggests that despite potentially traveling through interstellar space for millions or even billions of years, the comet’s basic structure and composition remain similar to icy bodies found closer to home.

A Proven and Reliable Measurement Technique

The method used to derive these water production rates is not experimental or speculative. It was first developed more than 20 years ago and has since been refined using observations of over 90 comet apparitions. The process combines SWAN’s hydrogen measurements with daily data on solar ultraviolet output and corrections for the Sun’s rotation, which affects how much radiation reaches the comet at any given time.

Each of these factors matters, because the fluorescence of hydrogen depends directly on the Sun’s ultraviolet activity. This careful calibration gives scientists confidence that the numbers derived for 3I/ATLAS are robust.

What This Comet Reveals About Other Star Systems

The significance of 3I/ATLAS goes far beyond a single object. This comet formed around another star, possibly billions of years ago, before being ejected into interstellar space. By studying its behavior and composition, astronomers gain a rare opportunity to compare planet formation processes across different stellar systems.

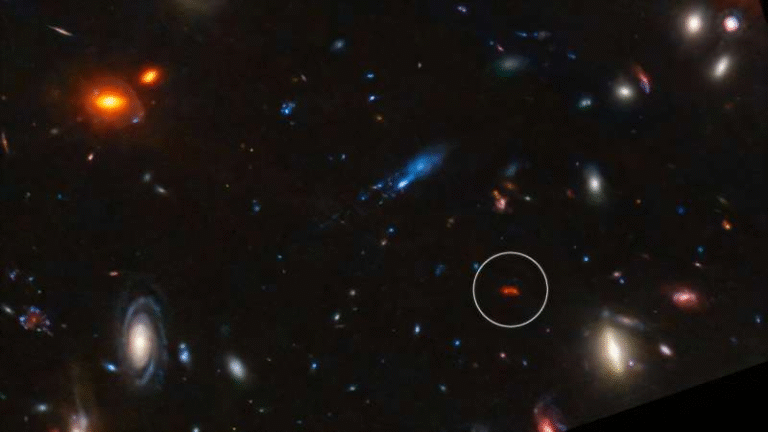

One particularly intriguing result concerns the comet’s nucleus size and surface activity. Observations from the Hubble Space Telescope suggest the nucleus is somewhere between 440 meters and 5.6 kilometers in diameter. To produce the observed amount of water, a surprisingly large fraction of the surface—possibly around 20%—must be actively sublimating ice. For comparison, most solar system comets show active fractions closer to 3–5%.

This raises interesting questions about whether interstellar comets tend to have fresher surfaces, different internal structures, or simply more exposed ice than their solar system counterparts.

How Interstellar Comets Compare to Solar System Comets

Despite its alien origin, 3I/ATLAS does not appear fundamentally exotic. Its decline in activity with distance, its strong water production near perihelion, and its response to solar heating all closely resemble the behavior of comets that formed in our own solar system’s distant past.

This similarity suggests that the basic building blocks of comets may be common throughout the galaxy. If icy planetesimals form in broadly similar ways around different stars, then studying objects like 3I/ATLAS can help scientists understand how widespread certain conditions for planet formation really are.

A Brief Visit, a Lasting Impact

After its passage through the inner solar system, 3I/ATLAS is now on its way out, destined to wander the galaxy for countless millennia before possibly passing another star. While its visit was brief on cosmic timescales, the amount of data collected during those few weeks has been extraordinary.

Thanks to instruments like SWAN and the coordinated efforts of ground-based and space-based observatories, astronomers have captured the most detailed snapshot yet of an interstellar comet in action. Each new measurement adds to a growing picture of a universe where planetary systems may be more alike than we once imagined.

Research paper:

M. R. Combi et al., Water Production of Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS from SOHO/SWAN Observations after Perihelion, arXiv (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2512.22354