Thin Ice May Have Protected Lake Water on Frozen Mars

Scientists have long faced a frustrating contradiction when studying ancient Mars. On one hand, the planet’s surface is covered with clear geological signs of long-lasting liquid water—ancient lake beds, preserved shorelines, layered sediments, and water-altered minerals. On the other hand, most climate models suggest that early Mars was far too cold to keep liquid water stable at the surface for long periods. A new study may finally bridge this gap, offering a surprisingly simple explanation: thin, seasonal ice.

Recent research led by scientists at Rice University suggests that small lakes on ancient Mars could have remained liquid for decades, even while average air temperatures stayed well below freezing. Instead of requiring a warm, Earth-like climate, these lakes may have survived under a thin, temporary ice cover that formed and melted with the seasons.

This idea not only fits the available geological evidence but also reshapes how scientists think about Mars’ climate, surface water, and even its potential to support life billions of years ago.

Why Ancient Martian Lakes Are So Puzzling

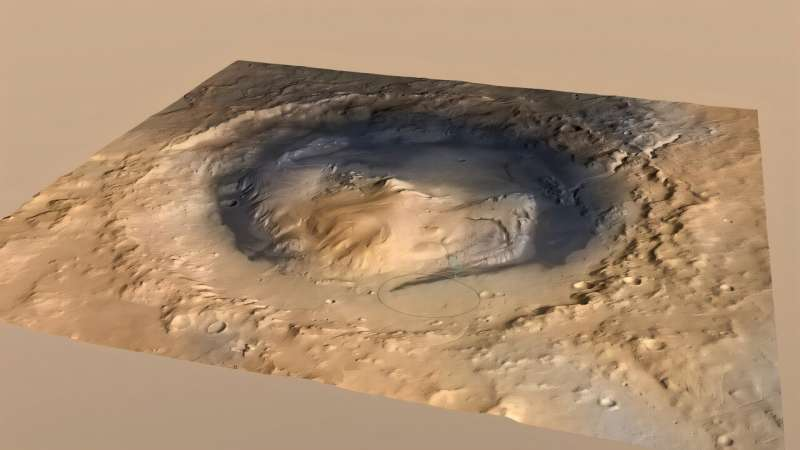

Mars today is cold, dry, and hostile to liquid water. But the planet’s surface tells a different story about its distant past. Features such as Gale Crater, explored by NASA’s Curiosity rover, contain sedimentary layers that strongly suggest the presence of long-lived lakes around 3.6 billion years ago.

The problem is that traditional climate models struggle to explain how those lakes could exist. Early Mars received less sunlight than Earth, had weaker greenhouse warming, and likely experienced long periods of freezing temperatures. Under those conditions, lakes should have either frozen solid or evaporated quickly.

For years, scientists debated whether Mars must have gone through brief warm periods, intense volcanic warming, or short-lived climate anomalies. None of those explanations fully solved the puzzle.

A Climate Model Built for Another Planet

To explore a new possibility, the research team adapted an Earth-based climate modeling tool known as Proxy System Modeling. This tool is typically used to reconstruct Earth’s ancient climates using indirect evidence like tree rings or ice cores.

Mars, of course, has no trees or ice cores from its deep past. Instead, the researchers relied on rock chemistry, mineral data, and sediment records collected by Mars rovers as climate proxies. Over several years, they reworked the model to account for Martian gravity, weaker sunlight, a carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere, and unique seasonal cycles.

The result was a new model called Lake Modeling on Mars with Atmospheric Reconstructions and Simulations, or LakeM2ARS.

Using LakeM2ARS, the team ran 64 different simulations, each representing a hypothetical lake inside Gale Crater. Every simulation covered 30 Martian years, which equals roughly 56 Earth years. This long runtime allowed the researchers to test whether lakes could realistically persist under various atmospheric pressures, temperature swings, and seasonal patterns.

What the Simulations Revealed

The results were striking. In some simulations, lakes froze completely during colder seasons. But in many others, something different happened. Instead of freezing solid, the lakes developed a thin layer of ice that formed during cold periods and melted when temperatures rose.

This thin ice layer acted as a natural insulating blanket. It reduced heat loss from the water below, limited evaporation, and still allowed sunlight to penetrate and warm the lake during warmer seasons. Because the ice was seasonal and relatively thin, it prevented the lake from freezing through while avoiding the buildup of thick, permanent ice.

Over decades, some simulated lakes showed very little change in depth, meaning they could remain stable for long periods even though the surrounding air stayed mostly below freezing.

Why Thin Ice Makes Sense on Mars

This finding helps explain several long-standing observations. If Martian lakes were covered by thick, permanent ice, scientists would expect to see strong glacial signatures or extensive ice-related landforms. However, rover missions have not found clear evidence of widespread glaciers in ancient lake basins.

Thin, seasonal ice would leave very little geological trace, especially after billions of years of erosion and dust accumulation. That aligns well with what we see today: preserved lake features without obvious signs of long-term ice sheets.

This mechanism also explains how Mars could host liquid water without requiring a warm global climate, resolving the mismatch between geological evidence and climate simulations.

Rethinking Early Mars’ Climate

The study challenges the idea that early Mars had to be consistently warm to support surface water. Instead, it suggests a cold but stable climate, where lakes could persist locally under the right conditions.

Key factors included:

- Atmospheric pressure high enough to limit rapid evaporation

- Seasonal temperature variations that allowed ice to form and melt

- Carbon dioxide-rich air that provided modest greenhouse warming

Together, these elements created an environment where lakes could survive far longer than previously assumed.

What This Means for Martian Habitability

Liquid water is one of the most important ingredients for life as we know it. If lakes on Mars persisted for decades or longer, even under cold conditions, they could have provided stable environments for chemical reactions essential to life.

Thin ice may have even been beneficial. Ice can protect water from harmful radiation while still allowing sunlight to pass through, creating a shielded yet energized environment. On Earth, similar conditions exist in icy lakes and polar regions where microbial life thrives beneath ice covers.

If this thin-ice mechanism worked in Gale Crater, it may have operated in other Martian basins as well, potentially expanding the number of locations that could once have been habitable.

Where the Research Goes Next

The researchers plan to apply the LakeM2ARS model to other regions of Mars to see if similar lakes could have existed elsewhere on the planet. They also want to explore how changes in atmospheric composition, groundwater flow, and long-term climate shifts might have influenced lake stability.

If similar results appear across multiple sites, it would strengthen the case that cold early Mars was still capable of sustaining liquid water, at least locally and seasonally.

Extra Context: Ice-Covered Lakes Beyond Mars

Ice-covered lakes are not just a Martian concept. On Earth, lakes in Antarctica remain liquid beneath thick ice for thousands of years. While Mars’ lakes would have had thinner ice, the underlying physics is similar: ice slows heat loss and stabilizes liquid water.

Scientists also suspect that icy moons like Europa and Enceladus use similar mechanisms to maintain subsurface oceans. Mars now joins this broader planetary pattern, showing that liquid water does not always require warmth—sometimes it just needs the right kind of protection.

A Simpler Explanation With Big Implications

By showing that thin, seasonal ice could preserve liquid lakes on a cold Mars, this research offers a solution that is both elegant and consistent with real data. It avoids extreme assumptions, fits rover observations, and opens new doors in the search for past habitable environments.

Ancient Mars may have been cold, but it was not necessarily dry or lifeless. Sometimes, all it takes is a thin layer of ice to change everything.

Research paper:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2025AV001891