To Understand Exoplanet Habitability, Scientists Need a Much Better Grasp of Stellar Flaring

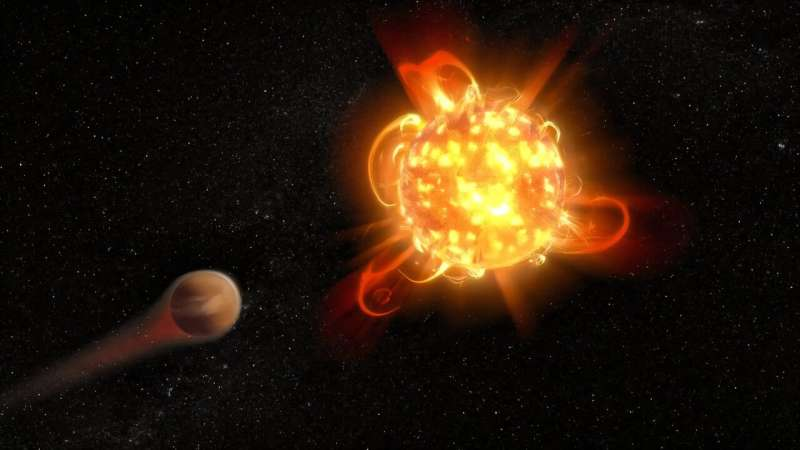

One of the biggest open questions in modern astronomy is whether planets beyond our Solar System can actually support life. While thousands of exoplanets have been discovered so far, determining whether any of them are truly habitable depends on more than just their size or distance from their star. A growing body of research now points to one critical factor that is still poorly understood: stellar flaring, especially around red dwarf stars.

Why Red Dwarfs Matter So Much

Red dwarfs, also known as M dwarfs, are small, cool stars that make up as much as 70% of the stars in the Milky Way. Because they are so common, they host a large fraction of the rocky exoplanets astronomers have identified so far. Research has shown that Earth-sized planets are particularly abundant around these stars.

Another reason red dwarfs attracted early excitement is their longevity. These stars evolve slowly, meaning their habitable zones—the region where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface—can remain stable for billions of years. At first glance, that seems ideal for life.

However, there’s a major catch.

Because red dwarfs are small and dim, their habitable zones lie extremely close to the star itself. Any planet orbiting in this zone is exposed to intense stellar activity, including frequent and powerful flares. This puts potentially habitable planets directly in the line of fire.

The Problem With Stellar Flares

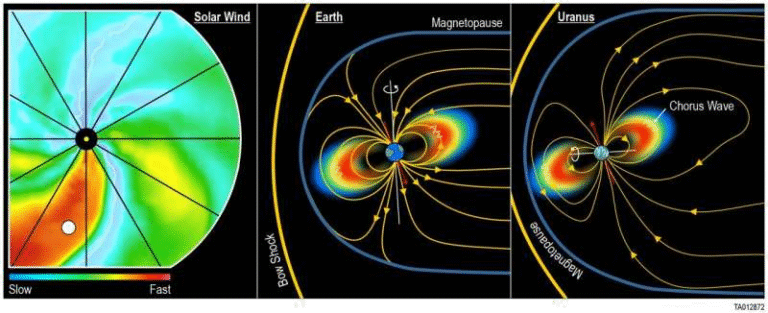

Stellar flares are sudden releases of magnetic energy that produce intense bursts of ultraviolet (UV), extreme ultraviolet (EUV), and X-ray radiation. These events are often accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs)—huge eruptions of hot, magnetized plasma.

While our Sun does produce flares and CMEs, its activity is relatively mild compared to many red dwarfs. Some stars generate superflares, which release at least ten times more energy than the most powerful solar flares ever observed. Red dwarfs are especially prone to these extreme events, though some Sun-like (G-type) stars have also been observed producing them. Notably, the Sun itself has never been seen generating a superflare.

The concern is straightforward: repeated exposure to this kind of radiation can strip away planetary atmospheres, erode protective ozone layers, and bathe the planet’s surface in sterilizing UV radiation.

How Bad Can It Get?

According to recent research cited in a new white paper, high-energy flares occurring as often as once per month may be enough to completely destroy a planet’s ozone layer. Without ozone, a planet’s surface is exposed to intense UV radiation that could make complex life extremely difficult—or even impossible—to sustain.

This matters because, as of late 2025, astronomers have identified about 70 exoplanets that meet the basic temperature requirement for liquid water. Roughly 50 of these orbit M dwarf stars, which are known for their strong chromospheric activity, including flares and CMEs.

The TRAPPIST-1 Example

A well-known example of this dilemma is the TRAPPIST-1 system. It consists of a small red dwarf star orbited by seven rocky, Earth-sized planets. At least three of them lie within the star’s habitable zone.

On paper, TRAPPIST-1 looks like one of the most promising systems for life beyond Earth. In reality, its host star is highly active, raising serious concerns about whether those planets can retain atmospheres long enough to remain habitable.

Why We Know So Little About Stellar Flaring

One of the biggest challenges is that astronomers have excellent data on the Sun, but far less detailed information about other stars. Dedicated missions like the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Dynamics Observatory allow scientists to observe solar flares across multiple wavelengths in extraordinary detail.

For stars beyond the Solar System, however, spectroscopic data on flares is sparse. Researchers lack detailed information on flare energy distributions, radiation spectra, and how flaring behavior changes over time with stellar age and type.

This gap in knowledge has effectively slowed progress in assessing exoplanet habitability.

A New White Paper Takes Aim at the Problem

To address this issue, a new white paper titled Habitability of Exoplanets Orbiting Flaring Stars has been submitted to the European Southern Observatory’s Expanding Horizons initiative. The study is led by Rebecca Szabó of the Astronomical Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences and is available on the arXiv preprint server.

The authors argue that accurately assessing habitability requires reliable estimates of flare energies and frequencies, since radiation and energetic particles have a profound influence on planetary atmospheres.

They outline two major scientific goals:

- Building a clear picture of flare frequency and power distributions across different stellar types and ages

- Understanding how stellar activity affects the long-term potential for complex life

The latter goal may even require collaboration with biologists who study extremophiles, organisms that thrive in extreme conditions on Earth. Even then, the authors note that our understanding of biology itself may change significantly over the next 10 to 15 years.

The Telescope Scientists Say We Need

To move forward, the white paper describes the type of observatory required to break the current impasse. The authors propose a facility capable of:

- Continuous, high-cadence monitoring of large numbers of late-type stars

- Rapid follow-up observations of stars when flares are detected

The ideal telescope would have a primary mirror larger than 4 meters, a wide field of view of 1 to 3 degrees, and extreme multiplexing capability. The authors suggest a system with around 30,000 optical fibers, allowing astronomers to collect spectra from thousands of stars simultaneously.

Such a design would dramatically increase the speed and scale of stellar flare surveys.

They also point to China’s Wide Field Survey Telescope (WFST)—a 2.5-meter instrument focused on time-domain astronomy—as an example of the kind of approach that could help advance this research.

Flares Aren’t Always Bad News

Interestingly, stellar flaring isn’t entirely negative. Research has shown that some amount of UV radiation may be necessary for the formation of biotic compounds. Studies from 2018 demonstrated that prebiotic chemistry can be linked directly to a star’s UV spectrum.

In this sense, flares could provide the energy needed to kick-start life. The challenge lies in finding the right balance. Too little UV, and important chemical reactions may never occur. Too much, and the planet’s surface becomes hostile to life.

The Bigger Picture

Right now, astronomers know of only a few dozen exoplanets that appear potentially habitable. As new telescopes like ESA’s PLATO mission—designed to find and characterize rocky planets in habitable zones—come online, that number is expected to grow.

But without a deeper understanding of stellar flaring, scientists risk misclassifying worlds as habitable when they may not be—or overlooking environments where life could survive despite intense stellar activity.

Large-scale surveys of stellar flares could finally answer a crucial question: Can stars with strong flaring activity still host habitable planets?

According to the authors, a comprehensive study of flaring exoplanet hosts—far beyond the few dozen known today—is essential. Only then can astronomers determine whether planets around active stars truly stand a chance of supporting life.

Research paper reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.21357