Two Massive Hot Stars Passed Near Our Solar System Millions of Years Ago and Scientists Can Still See the Evidence

Nearly 4.5 million years ago, long before humans appeared on Earth, our solar system had a surprisingly close encounter with two enormous, blazing-hot stars. They didn’t crash through the solar system or disrupt planets, but they left behind something just as fascinating — a lasting chemical fingerprint in the gas and dust surrounding the Sun. New research shows that astronomers can still detect this ancient encounter today, written into the structure of space just beyond our solar system.

The study, led by astrophysicist Michael Shull of the University of Colorado Boulder, was published in The Astrophysical Journal and focuses on how nearby stars shape the environment around the Sun over millions of years. It turns out that our cosmic neighborhood is far more dynamic — and interconnected — than it may appear at first glance.

The Solar System’s Immediate Neighborhood

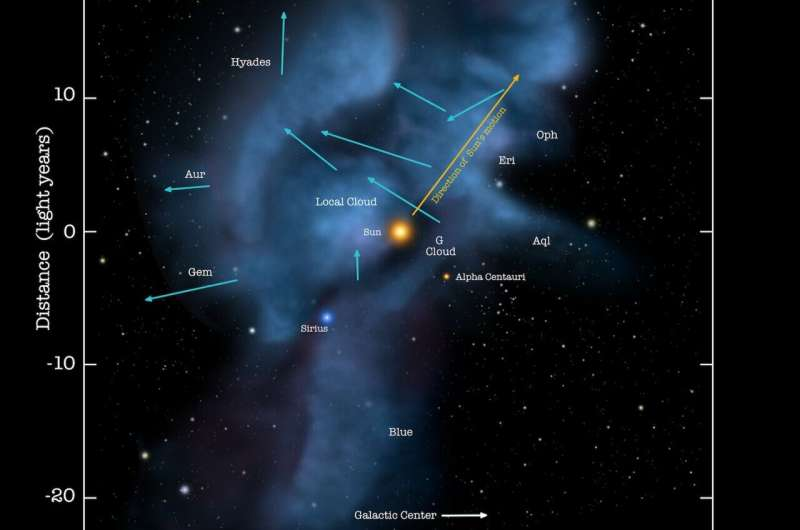

Our solar system does not travel through empty space. Instead, it is embedded within a region known as the local interstellar clouds. These clouds are thin, wispy collections of gas and dust made primarily of hydrogen and helium atoms. Together, they stretch about 30 light-years across, which is roughly 175 trillion miles from end to end.

Beyond these clouds lies a much larger and hotter region of space called the Local Hot Bubble. This bubble contains very little dense material and is filled with superheated gas, likely created by multiple ancient supernova explosions. The Sun and its planets currently sit near the boundary between these two regions.

Understanding this environment matters because interstellar clouds can act as a protective shield, blocking some of the most harmful ionizing radiation from reaching Earth. Over geological timescales, that shielding may have played a role in maintaining conditions suitable for life on our planet.

The Two Stars That Came Close

The new research zeroes in on two specific stars: Epsilon Canis Majoris and Beta Canis Majoris. Today, these stars are located more than 400 light-years away in the constellation Canis Major, also known as the Great Dog. Epsilon Canis Majoris marks the dog’s rear leg, while Beta Canis Majoris marks its front leg.

However, based on detailed models of stellar motion, researchers determined that around 4.4 million years ago, these stars passed within 30 to 35 light-years of the Sun. In astronomical terms, that counts as a very close brush.

At the time of this encounter, both stars were far brighter than they appear today. In fact, calculations suggest they would have been four to six times brighter than Sirius, currently the brightest star in Earth’s night sky. If humans had existed back then, these stars would have dominated the heavens.

Why These Stars Were So Influential

Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris are classified as B-type stars. These stars are significantly more massive and hotter than the Sun. Each has about 13 times the Sun’s mass and burns at temperatures of approximately 38,000 to 45,000 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to the Sun’s roughly 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Because of their extreme heat, B-type stars emit enormous amounts of ultraviolet radiation. When these two stars passed near the Sun millions of years ago, their radiation ionized the surrounding interstellar clouds. Ionization occurs when radiation strips electrons from atoms, leaving them with a positive electrical charge.

This process altered the physical state of the gas around our solar system — and remarkably, those changes are still measurable today.

A Long-Standing Scientific Mystery

For decades, astronomers have known that the local interstellar clouds are unusually ionized. Observations from instruments such as the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that about 20% of hydrogen atoms and an even more puzzling 40% of helium atoms in these clouds are ionized.

Helium is especially difficult to ionize, requiring higher-energy radiation than hydrogen. The high level of ionized helium has therefore been a major scientific puzzle. Known sources of radiation didn’t seem powerful enough to explain it.

This new study helps solve that mystery.

Rewinding the Galactic Clock

To identify the sources of this ionization, the research team created detailed models that simulate the motion of stars, gas clouds, and the Sun itself over millions of years. This is no easy task. The Sun is racing through the Milky Way at about 58,000 miles per hour, while nearby stars and clouds are also constantly shifting.

The researchers found that at least six different sources likely contributed to ionizing the local interstellar clouds. These include:

- Epsilon Canis Majoris

- Beta Canis Majoris

- Three nearby white dwarf stars

- The hot, radiation-filled gas of the Local Hot Bubble

The study shows that the two B-type stars alone likely contributed as much ionization as the background radiation from the Local Hot Bubble itself.

The Role of the Local Hot Bubble

The Local Hot Bubble is thought to have formed after 10 to 20 massive stars exploded as supernovae millions of years ago. These explosions cleared out much of the surrounding gas, leaving behind a cavity filled with hot plasma that continues to emit ultraviolet and X-ray radiation.

That radiation still “bakes” the interstellar clouds surrounding our solar system today, maintaining their partially ionized state. The close pass of Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris added a significant burst of energy to this already active environment.

How Long Will the Evidence Last?

The ionization caused by these stars is not permanent. Over millions of years, positively charged atoms gradually capture free electrons, returning to a neutral state. Eventually, the chemical imprint of this stellar encounter will fade.

The stars themselves also have limited time left. B-type stars burn through their fuel quickly and typically live for no more than 20 million years. Scientists estimate that both Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris may go supernova within the next few million years.

While such explosions would create an extraordinarily bright light show in Earth’s sky, they would be far enough away to pose no threat to life on our planet.

Why This Research Matters

This work highlights how events far beyond our solar system can still shape the environment Earth inhabits. The Sun’s position within ionized interstellar clouds may help moderate cosmic radiation, subtly influencing planetary conditions over vast timescales.

More broadly, the study demonstrates that our galaxy is a living, evolving system, where stars, clouds, and radiation interact in complex ways. Even millions of years after a stellar encounter, space still remembers.

Research Reference

Ionization Sources of the Local Interstellar Clouds: Two B Stars, Three White Dwarfs, and the Local Hot Bubble

The Astrophysical Journal (2025)

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae10a6