Two New Exoplanets Are Forcing Astronomers to Rethink What “Habitable” Really Means

At the very beginning of exoplanet science, astronomers had a fairly straightforward goal: find planets beyond our Solar System and figure out whether any of them might support life. Back then, the idea of a habitable zone was simple and practical. If a planet orbited its star at just the right distance to allow liquid water to exist on its surface, it was considered potentially habitable. That definition worked well when only a handful of exoplanets were known.

Fast forward to today, and the situation has changed dramatically. Thousands of exoplanets have now been discovered, ranging from scorched lava worlds to gas giants hugging their stars and mysterious planets that don’t fit neatly into any Solar System category. With this growing diversity, scientists are realizing that the old, narrow definition of habitability may no longer be enough.

New research published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society introduces two newly discovered exoplanets and, more importantly, proposes a broader and more flexible way to think about planetary environments that might be scientifically interesting—or even life-friendly.

Why the Classic Habitable Zone Needed an Upgrade

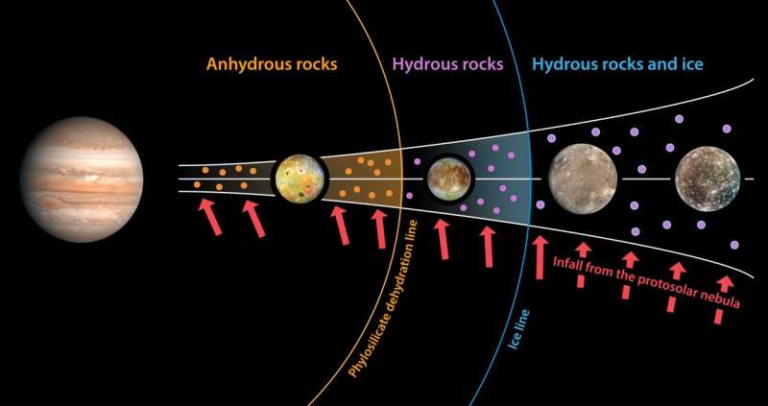

The traditional habitable zone is based on a planet’s ability to maintain liquid water on its surface. Over time, astronomers refined this idea into two main versions: the optimistic habitable zone and the conservative habitable zone.

The optimistic version stretches the boundaries. It accounts for factors like geothermal heating, which could keep a planet warm farther from its star, or atmospheric circulation and rotation patterns that might prevent runaway greenhouse effects closer in. The conservative habitable zone is stricter. Its inner edge marks where greenhouse heating becomes extreme, while its outer edge is defined by the point where carbon dioxide condenses out of the atmosphere, reducing a planet’s ability to stay warm.

Even with these refinements, scientists noticed a growing problem. Many newly discovered exoplanets didn’t fit neatly inside either definition, yet still seemed worthy of further study. Some were too hot or too cold by classic standards but received moderate amounts of stellar energy, making them intriguing candidates for atmospheric research.

Introducing the Temperate Zone

The new study tackles this issue by introducing a clearly defined temperate zone, a concept that has been loosely used in past research but rarely standardized.

In this work, the temperate zone is defined by instellation flux, also known as insolation. This measures how much stellar energy reaches a planet, relative to what Earth receives from the Sun. The researchers define the temperate zone as planets receiving between 0.1 and 5 times Earth’s instellation.

To put that in perspective, Earth receives about 1361 watts per square meter at the top of its atmosphere. Under the new definition, temperate planets can receive anywhere from roughly 136 W/m² to 6,805 W/m². This is a much wider range than the conservative habitable zone and is intentionally designed to capture planets that experience moderate stellar heating, even if surface liquid water isn’t guaranteed.

The key idea here is that the temperate zone is not strictly about habitability. Instead, it’s about identifying planets that are neither frozen wastelands nor extreme infernos, making them valuable targets for deeper scientific investigation.

Two New Planets Expand the Picture

The study, led by Madison Scott from the University of Birmingham and Georgina Dransfield from the University of Oxford, reports the discovery of two temperate exoplanets orbiting fully convective mid-type M dwarf stars. These stars are small, cool, and dim compared to the Sun, but they play an outsized role in exoplanet research.

The first planet, TOI-6716 b, is an Earth-sized world, measuring between 0.91 and 1.05 Earth radii. Based on its size, it is most likely a rocky planet. The second, TOI-7384 b, is a sub-Neptune, measuring roughly 3.35 to 3.77 Earth radii, and likely has a rocky core surrounded by a thick hydrogen-helium atmosphere.

Neither planet lies within even the optimistic habitable zones of their stars. However, both sit firmly within the newly defined temperate zone, occupying a region of parameter space that has been relatively sparse until now.

Why M Dwarf Stars Matter So Much

M dwarfs, especially mid- to late-type ones with surface temperatures below 3400 Kelvin, are extremely important in the search for temperate planets. Because these stars are small and cool, planets don’t need to orbit very far away to receive moderate amounts of energy.

This makes such planets far more likely to transit, meaning they pass directly in front of their star from our point of view. Transits allow astronomers to measure planetary sizes, densities, and atmospheric properties with much greater precision. As a result, temperate planets around M dwarfs are among the best targets for detailed follow-up studies.

The Role of TEMPOS and SPECULOOS

This research also marks the launch of the TEMPOS survey, short for Temperate M Dwarf Planets With SPECULOOS. SPECULOOS itself is a network of telescopes designed to search for Earth-sized planets around ultra-cool stars.

TEMPOS focuses on building a catalog of temperate exoplanets with precisely measured radii, especially those orbiting fully convective M dwarfs. These planets are ideal candidates for future atmospheric studies using powerful observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope.

Atmospheric Potential and Future Observations

One of the most exciting aspects of TOI-6716 b is its predicted Transmission Spectroscopy Metric, or TSM. This metric estimates how favorable a planet is for atmospheric characterization. TOI-6716 b’s TSM is comparable to the famous TRAPPIST-1 planets, which are among the top targets for atmospheric studies today.

If TOI-6716 b has managed to retain an atmosphere, it could become an excellent target for JWST. TOI-7384 b, with its larger size and likely thick atmosphere, is also a strong candidate for atmospheric characterization, not just with JWST but with future observatories currently in development.

Why This Research Matters

Together, these discoveries highlight how exoplanet science is evolving. Instead of focusing solely on whether a planet could host Earth-like life, researchers are increasingly interested in building a broader, more inclusive framework that reflects the true diversity of planetary systems.

By defining a clear temperate zone, astronomers can better organize exoplanet populations, prioritize observational targets, and refine their understanding of how planets form, evolve, and interact with their stars. These two new planets may not be habitable in the classic sense, but they represent crucial stepping stones toward a more complete picture of planetary environments across the galaxy.

Research paper: https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/526/3/0000/8424240