Ultramassive Black Holes and Their Galaxies Show Where Classic Scaling Laws Start to Fail

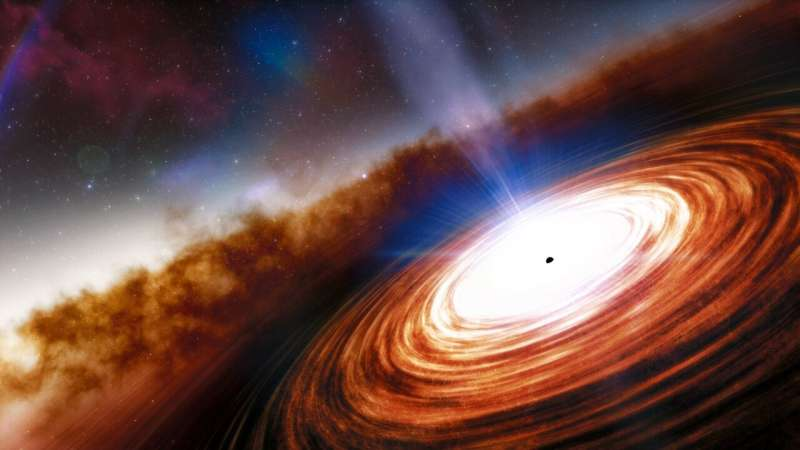

Nearly every large galaxy we observe today hosts a supermassive black hole at its center. These objects range from millions to billions of times the mass of our Sun, and for decades astronomers have known that the growth of these black holes is deeply connected to the evolution of their host galaxies. What remains uncertain is how tightly this connection holds at the extreme end of the scale—where black holes grow so massive that they begin to challenge our most trusted measurement tools.

A recent study sheds new light on this question by focusing on a rare and extreme class of objects known as ultramassive black holes, or UMBHs. These are black holes with masses exceeding 10 billion solar masses, far larger than most of the supermassive black holes commonly discussed in astronomy. The findings suggest that one of the most widely used methods for estimating black hole mass—the M–sigma relation—breaks down when applied to these cosmic giants.

The long-standing link between galaxies and black holes

Astronomers have long debated whether black holes form first and then shape their galaxies, or whether galaxies assemble first and feed their central black holes over time. While the exact sequence is still unclear, what is undeniable is that black hole growth and galaxy evolution are tightly coupled.

One of the strongest pieces of evidence for this connection is the M–sigma relation, a correlation between the mass of a galaxy’s central black hole (M) and the velocity dispersion (sigma) of stars near the galaxy’s core. Velocity dispersion is measured by analyzing how starlight is Doppler-shifted as stars orbit the galactic center. Stars moving toward us appear slightly blue-shifted, while those moving away are red-shifted. The statistical spread of these shifts reveals how fast stars are moving overall.

In general, a more massive black hole exerts a stronger gravitational pull, causing nearby stars to move faster and increasing the velocity dispersion. For decades, this relation has served as a powerful indirect tool for estimating black hole masses, especially when direct measurements are not possible.

Why the biggest black holes are a special case

The M–sigma relation works remarkably well for typical supermassive black holes, including the two that have been directly imaged so far. The black hole at the center of the galaxy M87, known as M87*, has a mass of about 6 billion Suns, while Sagittarius A* at the center of the Milky Way weighs in at around 4 million solar masses.

However, ultramassive black holes exist in a different regime altogether. These objects are most commonly found in brightest cluster galaxies, or BCGs, which sit at the centers of massive galaxy clusters and have long histories of mergers and growth. Because these galaxies are so large and complex, measuring their black holes accurately is especially challenging.

The new study set out to test whether the M–sigma relation still holds true for these extreme systems—or whether it begins to fail.

Measuring black holes with triaxial Schwarzschild models

To tackle this problem, the research team analyzed 16 brightest cluster galaxies and applied a sophisticated technique known as the triaxial Schwarzschild model. This approach simulates the full range of stellar orbits within a galaxy’s core, assuming the core has a three-axis elliptical shape rather than being perfectly spherical.

By modeling how stars move within this three-dimensional gravitational environment, astronomers can reproduce the galaxy’s brightness profile and infer the mass of the central black hole. While this method requires exceptionally detailed observations and heavy computational work, it provides one of the most reliable ways to measure black hole masses in inactive galaxies, where jets or bright accretion disks are absent.

Using this technique, the team was able to obtain robust mass measurements for eight ultramassive black holes, effectively doubling the number of UMBHs with well-constrained masses.

The M–sigma relation starts to break down

When the researchers plotted these newly measured black holes on an M–sigma graph alongside other galaxies, a clear pattern emerged. The ultramassive black holes consistently lay above the standard M–sigma relation, meaning their actual masses were significantly higher than what the relation would predict based on stellar velocity dispersion alone.

In simple terms, the M–sigma relation underestimates the mass of ultramassive black holes. While the relation remains useful for most galaxies, it no longer provides a reliable estimate once black holes reach the highest mass scales.

This result confirms growing suspicions among astronomers that scaling relations derived from smaller systems cannot be blindly extrapolated to the most extreme galaxies in the universe.

A better indicator: light-deficient galaxy cores

Recognizing this limitation, the researchers explored an alternative way to estimate black hole mass in these massive systems. Their solution lies in the structure of the galaxy’s core itself.

The largest black holes tend to consume or eject nearby stars over time, especially during galaxy mergers involving multiple black holes. As a result, many massive galaxies exhibit a central light-deficient region, where the brightness drops noticeably near the core.

The study found that the size of this depleted core correlates strongly with black hole mass, even more reliably than velocity dispersion for ultramassive black holes. In these cases, a larger light-deficient region generally indicates a more massive black hole.

This relationship offers astronomers a valuable new tool. Even when detailed triaxial modeling is not possible, core size measurements can still provide meaningful estimates of ultramassive black hole masses.

What this means for galaxy evolution

These findings have important implications for our understanding of galaxy formation and evolution, particularly in dense cluster environments. Brightest cluster galaxies grow primarily through mergers, and each merger can bring in another supermassive black hole. Over time, repeated mergers may lead to the formation of a single ultramassive black hole while simultaneously scouring stars from the galactic core.

This process naturally explains why core size and black hole mass are so closely linked in the most massive galaxies. It also suggests that feedback processes, stellar dynamics, and merger history play a larger role at extreme scales than previously thought.

Ultramassive black holes in a broader context

Ultramassive black holes remain rare, but they are increasingly important for testing the limits of our theories. Some galaxies, such as IC 1101 and Holmberg 15A, have long been suspected of hosting extraordinarily massive black holes based on indirect evidence. Studies like this one provide the direct measurements needed to confirm and refine those claims.

As telescopes and modeling techniques continue to improve, astronomers expect to identify more ultramassive black holes and better understand how they form. These objects may hold key clues to the early growth of galaxies, the role of mergers, and the ultimate limits of black hole mass.

Looking ahead

The takeaway from this research is clear: one size does not fit all when it comes to black hole scaling relations. While the M–sigma relation remains a cornerstone of black hole astronomy, it loses accuracy at the very top end of the mass spectrum. For ultramassive black holes, galaxy core structure tells a more reliable story.

As we push further into the extremes of the universe, studies like this remind us that even our most trusted tools need to be reexamined—and sometimes replaced—when the scale changes.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.04178