Webb Reveals an Early-Universe Lookalike Galaxy Has an Unexpected Talent for Making Cosmic Dust

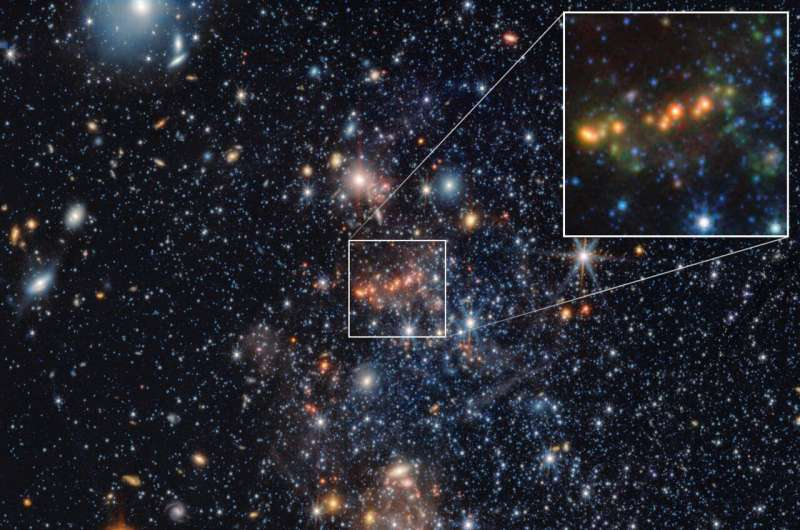

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has once again surprised astronomers, this time by uncovering something completely unexpected in a small neighboring galaxy called Sextans A. Despite being one of the most chemically primitive galaxies near the Milky Way, Sextans A is actively producing multiple kinds of cosmic dust—something scientists long believed should be extremely difficult under such conditions. These findings are reshaping how researchers think about dust formation, early galaxies, and the building blocks of planets.

Sextans A sits about 4 million light-years away and contains only 3–7% of the Sun’s metal content, with “metals” in astronomy meaning all elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. Galaxies like this closely resemble those that existed shortly after the Big Bang, before generations of stars enriched the universe with heavier elements. Because Sextans A is relatively close, astronomers can study it in remarkable detail, making it a powerful stand-in for understanding the early universe.

Using Webb’s extraordinary sensitivity in the infrared, astronomers discovered that this metal-poor galaxy is still finding ways to produce solid dust grains. And not just one kind—multiple rare and surprising types.

Why Sextans A Is So Important to Astronomers

Most galaxies near the Milky Way are chemically rich, filled with elements forged over billions of years of star formation and supernova explosions. Sextans A is different. Its small size means its gravity is too weak to hold onto many heavy elements created by dying stars. As a result, the galaxy has remained remarkably metal-poor.

This makes Sextans A a near-perfect analog of galaxies that populated the universe just a few hundred million years after it began. Studying it allows scientists to test long-standing theories about whether early galaxies could even produce dust at all. For years, the assumption was that dust formation required more metals than early galaxies possessed.

Webb’s observations now show that assumption was incomplete.

Aging Stars Making Dust Without the Usual Ingredients

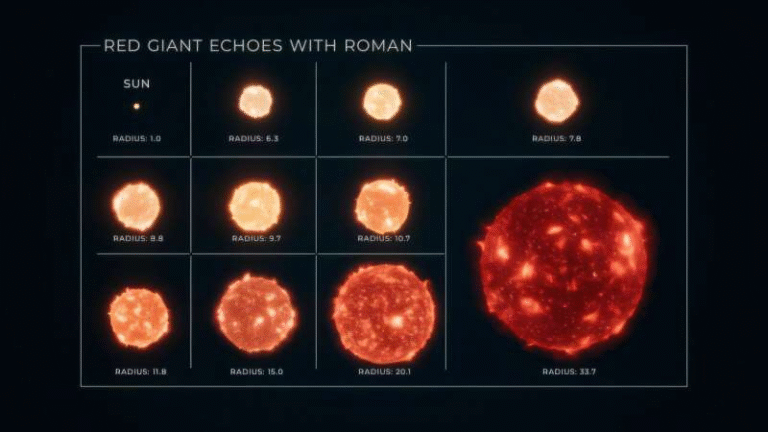

One part of the research focused on a small group of stars in the late stages of their lives, known as asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars. These stars, with masses between one and eight times that of the Sun, are known dust producers in metal-rich galaxies like the Milky Way.

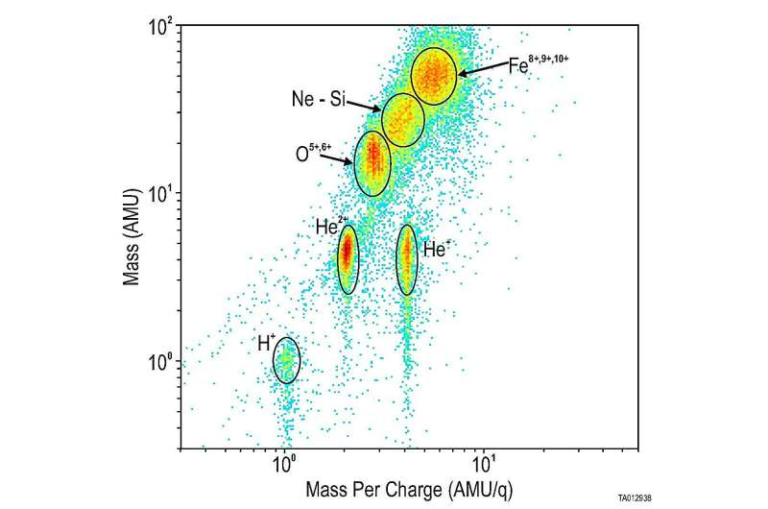

Using Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), astronomers analyzed about half a dozen AGB stars in Sextans A. The expectation was straightforward: at such low metallicity, these stars should be nearly dust-free.

Instead, Webb found something extraordinary.

One relatively massive AGB star was producing dust grains made almost entirely of iron. This kind of iron-dominated dust has never before been observed in stars that resemble those from the early universe. Normally, oxygen-rich stars produce silicate dust, which requires elements like silicon and magnesium—elements that are almost absent in Sextans A.

The situation has been compared to trying to bake cookies without flour, sugar, or butter. In a galaxy like the Milky Way, those ingredients are plentiful. In Sextans A, they are barely there. Yet the star found a different recipe entirely, forging dust from iron alone.

Other, less massive AGB stars in the galaxy were found producing silicon carbide (SiC) dust. This was equally surprising, given the galaxy’s extremely low silicon abundance. Together, these discoveries prove that evolved stars can still manufacture solid material even when the usual ingredients are missing.

Iron-rich dust also behaves differently from typical silicate dust. It absorbs light efficiently but lacks strong spectral fingerprints, meaning it could help explain why astronomers see large dust reservoirs in very distant galaxies without always being able to identify their composition clearly.

Tiny Islands of Organic Molecules in Harsh Conditions

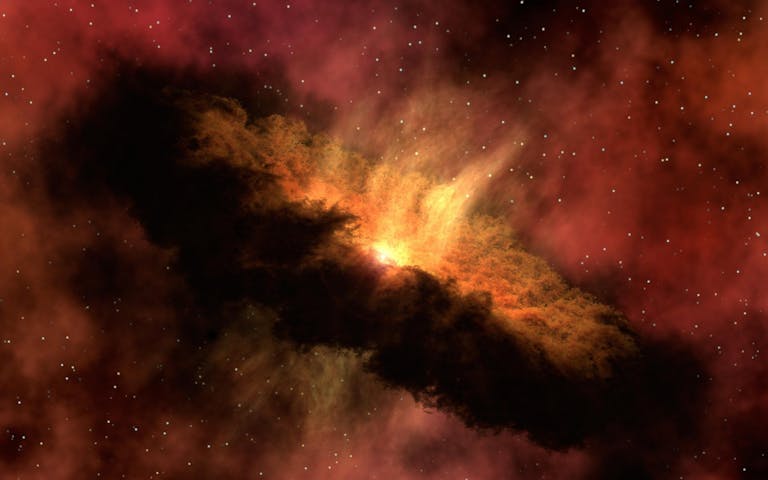

In a companion study, Webb turned its attention to the interstellar medium of Sextans A—the gas and dust between stars. Here, researchers detected polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), complex carbon-based molecules and some of the smallest dust grains known.

This discovery is particularly important because Sextans A is now the lowest-metallicity galaxy ever found to contain PAHs.

In metal-rich galaxies, PAHs tend to produce broad, widespread infrared emission. In Sextans A, Webb revealed something very different: PAHs exist only in tiny, dense clumps, each just a few light-years across.

These compact regions appear to be protected pockets where gas density and dust shielding are just high enough to allow PAHs to form and survive. This finding helps solve a long-standing puzzle about why PAHs seem to disappear in metal-poor galaxies. It turns out they don’t vanish entirely—they simply retreat into small, sheltered environments.

The research team has already secured time in Webb Cycle 4 to conduct high-resolution spectroscopy of these PAH clumps, aiming to map their detailed chemistry and better understand how complex carbon molecules grow under such extreme conditions.

What This Means for the Early Universe

Taken together, these results paint a picture of an early universe that was far more inventive than astronomers once imagined. Dust formation did not rely solely on supernova explosions or metal-rich environments. Instead, stars and interstellar gas found alternative pathways to create solid material.

This helps explain why astronomers observing extremely distant galaxies—galaxies seen as they were billions of years ago—often detect more dust than theoretical models predict. That dust may simply be different in composition from what we see locally today.

Understanding these processes is critical because dust plays a central role in cooling gas, forming stars, and eventually building planets. If dust could form earlier and under harsher conditions than previously thought, then the timeline for planet formation across cosmic history may need to be reconsidered.

How Webb Is Changing Cosmic Chemistry

The James Webb Space Telescope is uniquely suited for this kind of work. Its ability to observe in the infrared allows it to peer through dust and detect the subtle chemical signatures of molecules and grains that were invisible to earlier telescopes.

By studying nearby galaxies like Sextans A in exquisite detail, Webb gives astronomers a reference point for interpreting observations of galaxies billions of light-years away. These local analogs act as cosmic laboratories, bridging the gap between theory and observation.

Every new discovery in Sextans A reinforces the idea that the early universe was not chemically barren or simple. Instead, it was a place of unexpected complexity, where stars adapted to their environments and still managed to produce the raw materials needed for future generations of stars, planets, and possibly life.

Research Papers Referenced

Discovery of SiC and Iron Dust around AGB Stars in the Very Metal-poor Sextans A Dwarf Galaxy with JWST

https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adf06a

JWST Captures Growth of Aromatic Hydrocarbon Dust Particles in the Extremely Metal-poor Galaxy Sextans A

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.04060