Webb Telescope Finds a Curious “Blob” Near Epsilon Eridani, But Is It a Planet?

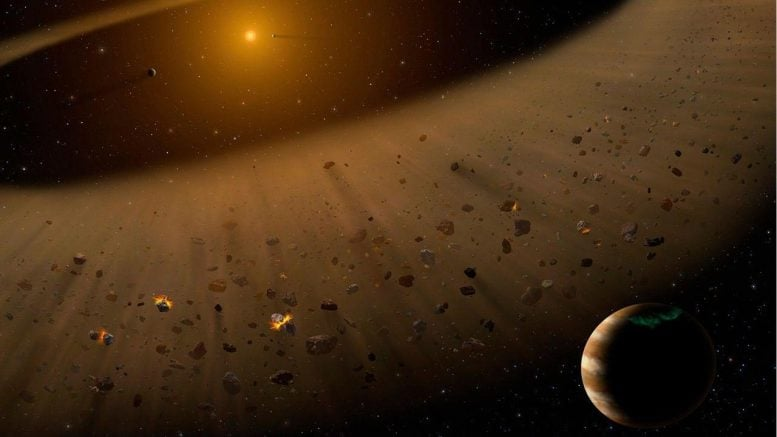

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has once again turned its powerful eyes toward one of our cosmic neighbors, the star Epsilon Eridani.

Located just 10.5 light-years away, this star has fascinated astronomers for decades because of hints that it might host planets—and possibly even a planetary system somewhat like our own. Recently, JWST picked up something intriguing: a mysterious “blob” of light that seemed to be in just the right place for a planet. But the story isn’t as simple as spotting a new world.

A Star with a History of Planetary Rumors

Epsilon Eridani isn’t just any nearby star—it’s relatively young, only about 400 million years old, and has been at the center of planetary debates for over twenty years. Back in 2000, astronomers suggested the existence of Epsilon Eridani b, a planet about the size of Jupiter orbiting the star at 3.5 AU (roughly the same distance as where the asteroid belt sits in our Solar System).

Another potential planet was thought to be further out, shaping the star’s dramatic ring system—much like how Saturn’s moons shepherd its rings.

The JWST observation program set out to finally provide clarity by hunting for these elusive worlds.

The Promising “Blob” That Wasn’t Quite Enough

While scanning for the inner planet candidate, JWST’s NIRCam instrument spotted a faint glow exactly where astronomers expected to see Epsilon Eridani b. Exciting, right? The problem is, that glow happened to sit dangerously close to a known instrument artifact called a “hexpeckle.”

Think of it as unwanted camera noise created by the telescope’s coronagraph.

Because of this interference, the team couldn’t confidently confirm the signal as a planet. It was tantalizingly close—but not quite enough to claim discovery.

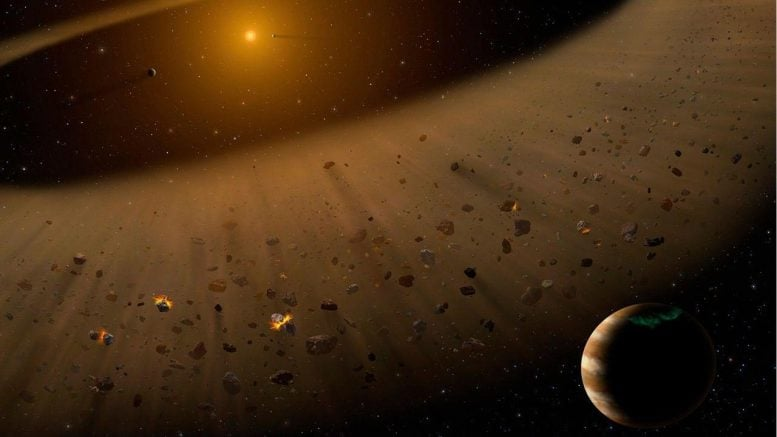

Ruling Out the Distant Candidate

The second, more distant planet candidate fared even worse. JWST’s observations were strong enough to rule out any Saturn-sized planets beyond 16 AU from the star.

This means the supposed “shepherd” of Epsilon Eridani’s rings is very likely not there. Instead, what JWST picked up was a faint light signal on the star’s eastern side, which turned out to be dust scattering starlight—beautiful, but not a planet.

A Win for New Techniques

Although the study didn’t provide a shiny new exoplanet headline, it delivered something equally valuable: a new way of observing faint objects. Normally, JWST uses a “two-roll” method—rotating to two different angles to check for consistency in its images.

For this study, scientists added a third roll, and the improvement was impressive. This “three-roll” strategy boosted JWST’s ability to detect faint signals by about 20–30%, a big deal for future planet-hunting missions.

Why This Matters

At first glance, not confirming a planet might sound disappointing. But in astronomy, ruling things out is just as important as making discoveries. Thanks to JWST, we now know more about what isn’t lurking around Epsilon Eridani, while also proving a powerful new observing method that will make the telescope even better at spotting elusive cosmic objects.

And let’s not forget—the star is just 10.5 light-years away, practically next door in galactic terms. With JWST’s long operational lifetime ahead, this won’t be the last time astronomers turn it toward Epsilon Eridani. The next time they do, that “blob” might just turn into a confirmed planet.

Source: Searching for Planets Orbiting ε~Eridani with JWST/NIRCam