Webb Telescope Sheds Light on Ancient Monster Stars That May Reveal the Birth of Black Holes

Using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have taken a major step toward solving one of the biggest mysteries in modern cosmology: how the universe’s first supermassive black holes were born. New research suggests that some of the most puzzling objects spotted by Webb—known as little red dots—may not be black holes or galaxies at all, but instead enormous, short-lived stars that existed in the early universe.

This work comes from scientists at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) and was presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS 2025) in Phoenix, Arizona. The study is now available as a preprint on arXiv, giving researchers worldwide a chance to examine the findings in detail.

What Are “Little Red Dots” and Why Do They Matter?

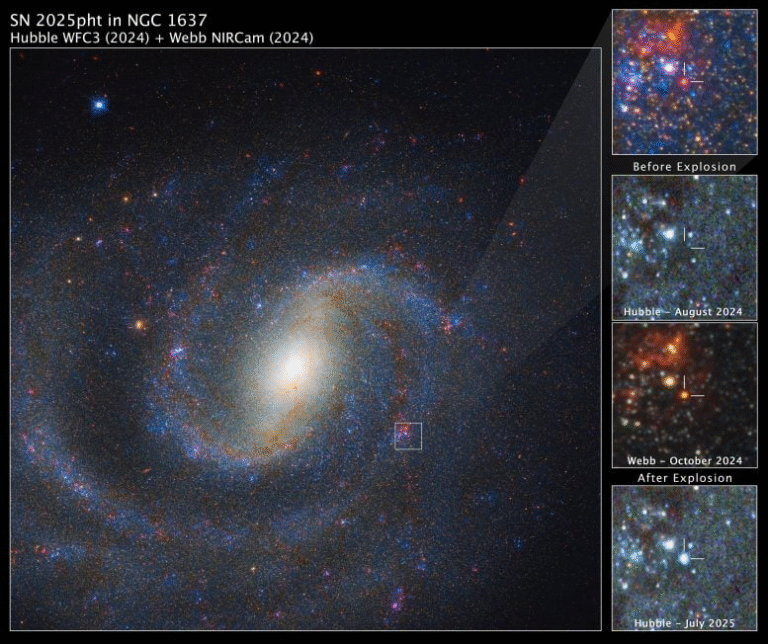

Little red dots are compact, extremely distant objects discovered in deep JWST images of the early universe. Because the universe is expanding, light from these ancient objects gets stretched to longer, redder wavelengths before reaching us. Earlier telescopes like Hubble were optimized for shorter wavelengths, so while they hinted at the presence of these objects, they couldn’t provide enough detail to explain what they were.

When JWST released its first deep-field images in 2022, astronomers finally saw these little red dots clearly. They appeared bright, compact, and very old, but their exact nature was unclear. Traditional explanations struggled to account for all their observed features at once.

Previous theories suggested that little red dots might be:

- Small galaxies hosting actively growing black holes

- Black holes surrounded by thick accretion disks

- Objects heavily obscured by dust clouds

While these ideas explained some observations, they required complex and fine-tuned conditions to work.

A Simpler Explanation: Supermassive Stars

The new CfA study offers a much simpler and potentially more powerful explanation. According to the researchers, little red dots may actually be single, gigantic stars, sometimes called supermassive stars, with masses reaching about one million times the mass of our Sun.

These stars are thought to be:

- Metal-free, meaning they formed before heavier elements existed

- Rapidly growing, fueled by enormous amounts of surrounding gas

- Extremely short-lived, surviving for only a brief period before collapsing

For the first time, the team built a detailed physical model of such a star and compared it directly with JWST observations. The match was striking.

Matching the Webb Observations

The researchers found that a single supermassive star can naturally reproduce all the key features seen in little red dots, including:

- Extreme brightness, consistent with the luminosity JWST measures

- A distinctive V-shaped spectrum, previously hard to explain

- A rare combination of strong hydrogen emission without other expected signals

While stars of many different masses can fit some of the spectral data, only the most massive stars reach the luminosities observed in these distant objects. This makes supermassive stars the best candidates for explaining the brightest little red dots detected so far.

Inside a Monster Star

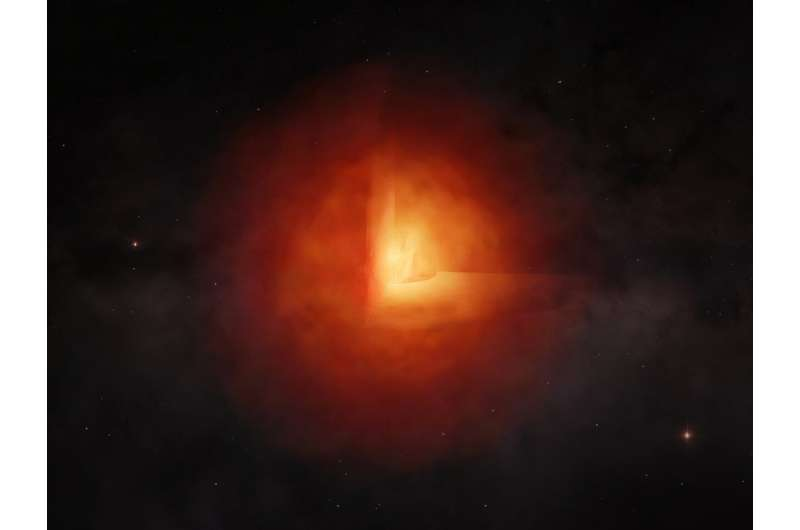

Artist impressions based on the model show a star with a dense, convective core where nuclear reactions generate immense energy. That energy moves outward as photons, but unlike normal stars, the outer layers of these giants are vast, extended, and loosely bound.

Because the energy spreads across such a huge volume before reaching the surface, the surface temperature drops. This gives the star a cooler, red appearance, despite the incredible power being produced at its core. This structure neatly explains why these objects look red and compact in JWST images.

A Missing Link in Black Hole Formation

One of the biggest puzzles in astronomy is how supermassive black holes—millions or billions of times heavier than the Sun—formed so quickly after the Big Bang. The universe simply wasn’t very old when these black holes already existed.

The new findings suggest that supermassive stars may be the missing link. When such a star exhausts its fuel, it can collapse directly into a massive black hole, skipping many of the slower growth steps seen in other models.

If this interpretation is correct, astronomers may be witnessing the final, brilliant moments before a black hole is born.

Why Not Just Black Holes from the Start?

Earlier explanations often assumed that little red dots were already black holes, but this raised problems. Black hole models typically predict:

- Strong X-ray emissions

- Additional spectral features tied to accretion disks

Many little red dots don’t show these signals clearly. The supermassive star model avoids these issues while still matching what JWST actually sees.

That said, scientists are careful not to claim that all little red dots are supermassive stars. Some may still turn out to be black holes or compact galaxies. The current study focuses on showing that a single massive star is a viable and compelling explanation for at least a subset of them.

What Comes Next?

The research team believes that finding less luminous and less massive little red dots will be crucial. If such objects exist and match predictions for smaller supermassive stars, it would strongly support the new model and help explain why and how these stars form in the first place.

Future JWST observations, especially deeper surveys and follow-up spectroscopy, will play a key role in testing these ideas.

Why This Discovery Matters

Understanding little red dots isn’t just about classifying strange objects. It directly impacts our understanding of:

- Early star formation

- The origin of supermassive black holes

- The growth of the first galaxies

Instead of relying on indirect clues or theoretical guesses, astronomers may now be observing black hole seeds forming in real time. That shift—from inference to observation—is a big deal for cosmology.

Extra Context: Supermassive Stars in Theory

Supermassive stars have been predicted for decades, but finding evidence for them has been difficult. They require very specific conditions:

- Huge inflows of pristine gas

- Minimal fragmentation into smaller stars

- Rapid growth before radiation blows material away

The early universe, before metals and dust became common, may have provided exactly the right environment. JWST’s ability to see faint infrared light from this era is what finally makes testing these theories possible.

A New Window into the Early Universe

This study highlights just how transformative the James Webb Space Telescope has been. By observing longer wavelengths with unprecedented sensitivity, Webb is revealing objects that were completely out of reach before. Little red dots may turn out to be one of its most important discoveries, not because they are mysterious, but because they offer direct insight into cosmic beginnings.

As more data comes in, astronomers will refine these models and may even catch different stages of these monster stars’ lives. For now, the idea that we are seeing giant stars on the verge of becoming black holes adds an exciting new chapter to our understanding of the universe.

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.12618