When Stars Fail to Explode and Create One of the Strangest Supernova Remnants Ever Seen

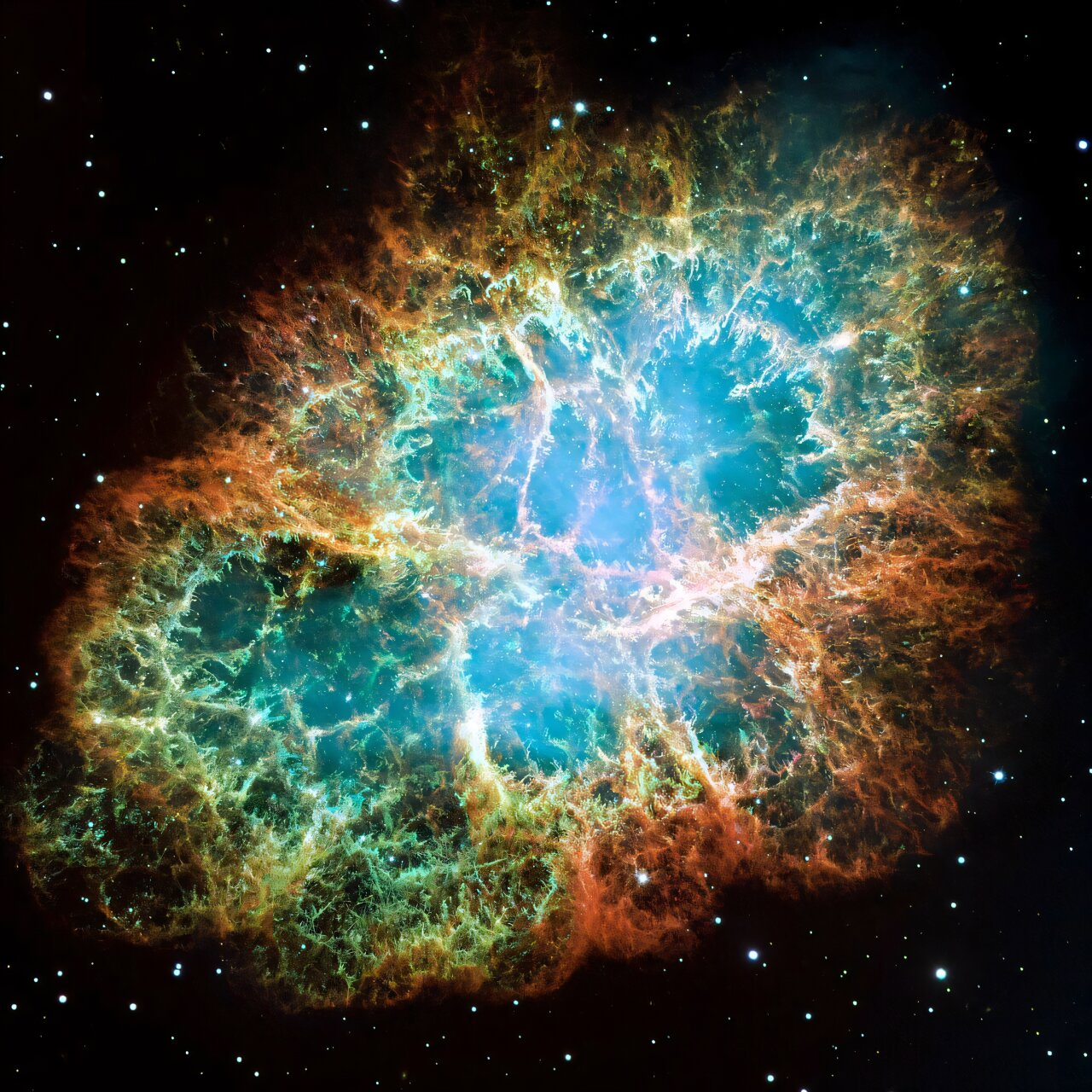

Many stars end their lives in spectacular fashion, tearing themselves apart in enormous explosions known as supernovae. These cosmic blasts usually leave behind messy, expanding clouds of debris that look chaotic and turbulent when viewed through powerful telescopes. But one object in our galaxy refuses to follow that script. Known as Pa 30, this supernova remnant looks nothing like the tangled wreckage astronomers expect. Instead, it resembles a frozen firework, with long, straight filaments shooting outward from a central point.

For years, Pa 30 puzzled astronomers. Its appearance didn’t match typical supernova remnants, yet its age and location seemed to line up with a mysterious “guest star” recorded in the year 1181 by Chinese and Japanese skywatchers. Now, new research led by astrophysicist Eric Coughlin of Syracuse University offers a compelling explanation: the star responsible for Pa 30 tried to explode, but the explosion failed partway through.

This idea not only explains Pa 30’s unusual structure but also sheds light on a rare and still poorly understood type of stellar death.

A Supernova That Didn’t Quite Finish the Job

Most supernovae involving white dwarfs fall into a category called Type Ia supernovae. In these events, a white dwarf star becomes unstable, ignites runaway nuclear fusion, and detonates completely. The star is obliterated, leaving behind no central object, only an expanding shell of debris rich in newly forged elements.

Pa 30 appears to come from a very different outcome.

According to the new study, the white dwarf at the heart of Pa 30 began nuclear burning near its surface, but the burning never transitioned into a full, supersonic detonation. Instead of ripping the star apart, the explosion fizzled. The result was a partial thermonuclear explosion that ejected some material but left behind a hyper-massive white dwarf still intact at the center.

This type of event belongs to a rare subclass known as Type Iax supernovae. These explosions are weaker than normal Type Ia events and, crucially, do not completely destroy the star. Until recently, astronomers had only indirect evidence that such survivors could exist. Pa 30 provides one of the clearest examples yet.

The Birth of an Extreme Stellar Wind

Surviving the failed explosion didn’t mean the white dwarf became quiet. Quite the opposite.

After the partial detonation, the remnant white dwarf began ejecting an extraordinarily fast wind, moving at roughly 15,000 kilometers per second. This wind was not only fast but also unusually dense and enriched with heavy elements created during the failed nuclear burning.

As this dense wind slammed into the surrounding, lighter interstellar gas, it set the stage for a well-known fluid process called the Rayleigh–Taylor instability. This instability occurs whenever a heavier fluid pushes into a lighter one, causing finger-like plumes to form. On Earth, it helps create the iconic mushroom shapes seen in explosions or fluid mixing experiments.

In Pa 30, those plumes grew into the long, straight filaments astronomers observe today.

Why Pa 30 Looks Like a Cosmic Firework

Normally, Rayleigh–Taylor fingers don’t stay neat for long. A second instability typically kicks in, shredding the structures into tangled, chaotic wisps. This is why most supernova remnants develop lumpy, cauliflower-like shapes over time.

Pa 30 avoided this fate for one key reason: density contrast.

The wind launched by the surviving white dwarf was so much denser than the surrounding material that the secondary instability never became effective. Without that disruptive mixing, the filaments remained intact. Even more importantly, the wind continued feeding the filaments, allowing them to stretch farther and farther outward rather than breaking apart.

The result is a structure that looks more like a sparkler frozen in mid-burst than a typical supernova remnant.

Simulations That Match Reality

Coughlin’s team didn’t stop at a theoretical explanation. They ran detailed hydrodynamical simulations to test whether this scenario could actually produce what astronomers see.

The simulations showed that when a dense, high-speed wind interacts with lighter surrounding gas, long-lived radial filaments naturally form. Under the right conditions, those filaments remain stable for centuries, matching Pa 30’s estimated age of about 840 years.

Remarkably, the patterns produced in the simulations closely resemble Pa 30’s real structure, strengthening the case that this remnant truly came from a failed supernova explosion.

An Unexpected Parallel With Nuclear Tests

One of the more surprising aspects of the research is an unexpected comparison with declassified photographs from the 1962 Kingfish nuclear test. Early moments after the detonation show filamentary structures that briefly resemble those seen in Pa 30.

In nuclear tests, however, those structures quickly collapse into chaotic turbulence. The difference again comes down to timing and density. Pa 30’s central wind kept pushing material outward over long periods, preventing the filaments from breaking apart and allowing them to persist for centuries rather than seconds.

Connecting Modern Science With Medieval Skywatchers

Pa 30 holds a special place in astronomy because it directly links modern astrophysical modeling with historical observations.

Records from Chinese and Japanese astronomers describe a guest star appearing in 1181 and remaining visible for about 185 days. For a long time, astronomers struggled to identify a corresponding remnant. Pa 30, discovered in infrared data in 2013, turned out to be an excellent match in both location and age.

That connection makes Pa 30 one of the very few supernova remnants in our galaxy that can be confidently tied to a specific historical event.

What Are Type Iax Supernovae?

Type Iax supernovae are still an active area of research. They are less energetic, fainter, and more diverse than normal Type Ia explosions. Some may eject only a fraction of the star’s mass, leaving behind compact remnants that continue evolving long after the initial blast.

Although they are relatively rare, Type Iax events may account for a significant fraction of white dwarf explosions. Understanding them is important not just for stellar evolution, but also for cosmology, since Type Ia supernovae are used as standard candles to measure cosmic distances.

Pa 30 provides a rare, nearby laboratory for studying what happens when a thermonuclear explosion almost—but not quite—destroys a star.

Broader Implications for Astrophysics

The mechanisms proposed for Pa 30 may apply to other extreme environments as well. Similar dense winds and filamentary structures could form during tidal disruption events, when stars are torn apart by black holes, or in other exotic stellar outbursts.

More broadly, Pa 30 reminds astronomers that stellar death is not always a clean, one-step process. Sometimes stars fail, sputter, and leave behind remnants that continue reshaping their surroundings in unexpected ways.

In the case of Pa 30, that failure produced one of the most visually striking and scientifically intriguing supernova remnants known, offering a rare glimpse into how stars can die not with a clean explosion, but with a complicated and beautiful aftermath.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.03140