Why Astronomy Needs a Giant Telescope in the Canary Islands

Size has always mattered in astronomy, and as the next few decades promise an explosion of discoveries, the case for building even bigger telescopes is becoming impossible to ignore. The latest push centers on a 30-meter-class telescope in the Northern Hemisphere, and a growing number of astronomers believe the Canary Islands, specifically La Palma, are the right place to build it.

A recent scientific paper led by Francesco Coti Zelati of the Spanish Institute of Space Sciences lays out a detailed argument for why a giant telescope is urgently needed in the north, why its location matters so much, and why the Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma stands out as a strong candidate. The paper was submitted as part of a major European astronomy planning effort and reflects years of discussion, frustration, and renewed optimism around one of the world’s most ambitious observatory projects.

Why bigger telescopes matter more than ever

Modern astronomy is driven by sensitivity and resolution. Larger telescopes collect more light, allowing astronomers to see fainter and more distant objects, resolve finer details, and study cosmic events that were once completely out of reach. Over the past two decades, this has led to the construction of so-called Extremely Large Telescopes, with mirror sizes far beyond the traditional 8–10 meter class.

Right now, the Southern Hemisphere is well covered. Chile hosts both the Extremely Large Telescope with a 39-meter mirror and the Giant Magellan Telescope with an effective aperture of about 25 meters. These facilities will dominate astronomy in the coming decades.

The Northern Hemisphere, however, has no comparable telescope in the 30–40 meter range. This creates a growing imbalance in what parts of the sky can be studied in the greatest detail. Some of the most important nearby galaxies, including Andromeda and Triangulum, sit largely in the northern sky and cannot be fully explored with the same power as southern targets.

The rise of multi-messenger astronomy

This gap is becoming especially problematic because astronomy is entering the era of multi-messenger observations. Instead of relying only on light, scientists now study the universe using gravitational waves, neutrinos, and high-energy particles, alongside traditional electromagnetic radiation.

When two black holes or neutron stars collide, gravitational-wave detectors can sense the event first. To understand what actually happened, astronomers then need powerful optical and infrared telescopes to observe the afterglow or related signals. These events evolve quickly, sometimes in minutes or hours, making rapid follow-up observations essential.

Future facilities like the Einstein Telescope in Europe and the Cosmic Explorer in the United States are expected to detect far more distant and frequent gravitational-wave events than current detectors. Without a giant optical telescope in the Northern Hemisphere, many of those discoveries could lack the detailed electromagnetic observations needed to fully interpret them.

In simple terms, we may soon be very good at detecting cosmic events, but not good enough at seeing them, at least in half the sky.

The original vision for the Thirty Meter Telescope

The Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) was conceived to solve exactly this problem. Planning began in the early 2000s, with the formal project established in 2003. Its goal was to create a northern counterpart to the giant telescopes being built in Chile.

In 2009, the TMT site was selected as Mauna Kea in Hawaiʻi, a location prized for its altitude, stable atmosphere, and excellent observing conditions. However, the project ran into intense opposition from Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners, who objected to further development on a mountain they consider sacred.

Construction was halted in 2014, right after a groundbreaking ceremony, and legal and social conflicts have delayed the project for more than a decade. While the scientific case for the TMT remained strong, progress on the ground effectively stopped.

Why La Palma entered the picture

By 2019, frustration within the astronomical community led to a serious reassessment. La Palma, part of Spain’s Canary Islands, emerged as a potential alternative site.

The Roque de los Muchachos Observatory already hosts several major telescopes and benefits from strict dark-sky protection laws, existing infrastructure, and a long history of successful international collaboration. While the atmospheric conditions are not quite as ideal as Mauna Kea’s, they are still excellent by global standards.

Another key advantage is geography. La Palma is only about four hours ahead of Chile in longitude, making it easier to coordinate observations between northern and southern observatories. This allows smoother hand-offs when tracking transient events that move across the sky or require continuous monitoring.

The new scientific justification

The new paper supporting La Palma was written to reassure funding agencies and decision-makers that moving the TMT would not compromise its science goals. It was submitted as a white paper to the European Southern Observatory’s long-term planning initiative, titled Expanding Horizons: Transforming Astronomy in the 2040s.

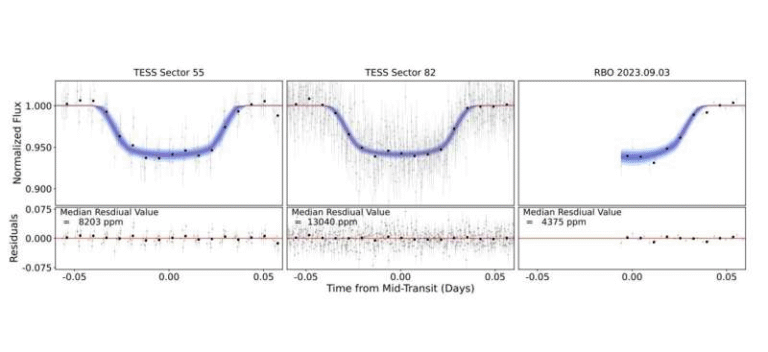

The authors emphasize that a northern 30–40 meter telescope would be transformative for time-domain astronomy, enabling studies of fast and unpredictable events such as stellar explosions, magnetar flares, and the optical counterparts of gravitational-wave sources.

They also highlight planned instrumentation, including ultra-fast photometers capable of capturing extremely rapid brightness changes, and broad wavelength coverage spanning optical to infrared light. These capabilities are essential for understanding the physics behind violent cosmic phenomena.

Funding shifts and political realities

The project’s financial landscape has also changed dramatically. In June 2025, the U.S. government withdrew its funding support for the TMT, creating a major budget gap and casting doubt on the project’s future.

In response, the Spanish government stepped in, offering to help cover the missing funds if the telescope is built in La Palma. This move has kept the project alive and strengthened the Canary Islands option, although a final construction agreement has not yet been reached.

Importantly, the astronomical community involved with the TMT has largely moved on from Mauna Kea as a realistic site, focusing instead on where the telescope can actually be built and operated within a reasonable timeframe.

Why timing matters so much

Astronomers hope to have the telescope operational by the late 2030s, aligning it with the next generation of gravitational-wave detectors. Missing that window would mean falling behind just as multi-messenger astronomy reaches its full potential.

Building a telescope of this scale is a massive engineering challenge, regardless of location. Delays only increase costs and risk losing scientific relevance. From this perspective, La Palma’s readiness and political support are major advantages.

A broader look at giant telescopes

Giant telescopes are not just about size. They rely on adaptive optics systems to correct for atmospheric distortion, segmented mirrors that act as a single surface, and highly specialized instruments tailored to specific science goals.

Together, these technologies allow astronomers to study exoplanet atmospheres, map dark matter in galaxies, trace stellar evolution, and probe the earliest stages of galaxy formation. A northern giant telescope would ensure that these studies are not limited by geography.

Looking ahead

The push to build a giant telescope in the Canary Islands is about more than replacing a stalled project. It reflects a broader recognition that balanced global coverage is essential for modern astronomy.

If successful, a La Palma-based 30-meter telescope would finally give the Northern Hemisphere the observational power it needs, closing a growing blind spot in our view of the universe and ensuring that future cosmic discoveries can be fully explored from every direction.

Research paper reference:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.14470