Why Being in the Right Place Isn’t Enough for Life on Other Planets

For decades, the search for life beyond Earth has revolved around a simple and appealing idea: find planets that sit in the so-called Goldilocks Zone, not too hot and not too cold, where liquid water could exist on the surface. This approach has guided how astronomers identify potentially habitable exoplanets and how telescopes are designed to study them. But new research suggests that this strategy only scratches the surface. According to a recent scientific study, where a planet is located may matter far less than how it was formed.

A new paper by Benjamin Farcy of the University of Maryland and his colleagues argues that a planet’s early formation conditions play a decisive role in determining whether it can ever support complex life. The study shifts the focus away from orbital distance alone and toward a deeper understanding of planetary chemistry, structure, and internal dynamics.

Why the Goldilocks Zone Is Only Part of the Picture

The Goldilocks Zone is defined by temperature. If a planet orbits its star at just the right distance, water can remain liquid on its surface. That idea is scientifically sound, but it is also incomplete. Many planets fall within this zone and yet may still be completely lifeless.

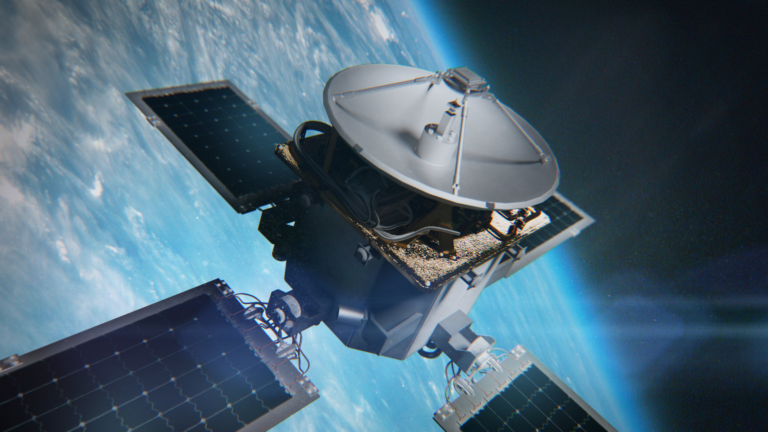

One major reason for this limitation is technological. Current instruments, including the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), can only analyze the atmospheres of relatively large planets that are close to Earth. Smaller, Earth-like planets remain frustratingly difficult to study in detail. As a result, astronomers have relied on indirect indicators like orbital distance as a proxy for habitability.

Future missions, especially NASA’s planned Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), are expected to change that. HWO is being designed specifically to study Earth-sized exoplanets and search for signs of habitability and life. The big question is: what exactly should it look for?

Planetary Formation Leaves a Lasting Fingerprint

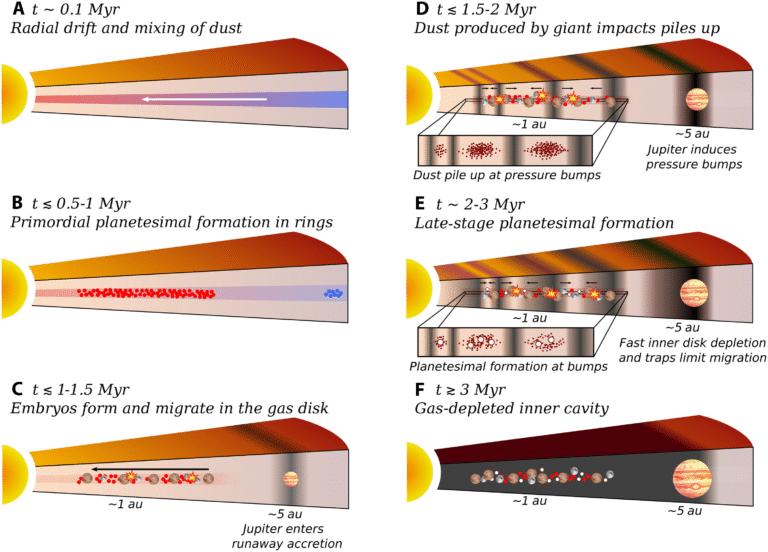

Farcy and his team propose that a planet’s habitability is shaped very early, during its formation inside a protoplanetary disk. They outline four major factors that are established early on and continue to influence a planet’s ability to host life billions of years later.

The first factor is bulk composition. Roughly 93% of terrestrial planets are made up of four elements: magnesium, iron, silicon, and oxygen. The ratios of these elements determine the planet’s internal structure, including whether it can support plate tectonics. Plate tectonics are critical because they help regulate climate, recycle carbon, and maintain long-term environmental stability.

Conveniently, scientists can estimate these elemental ratios by studying the planet’s host star. Since planets and stars form from the same cloud of material, their compositions are closely linked. This makes stellar spectroscopy a powerful tool for assessing planetary potential.

Volatiles: The Building Blocks of Life

The second major factor is the abundance of volatiles. In planetary science, volatiles are elements that easily vaporize at relatively low temperatures. These include carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur, often grouped together as CHNOPS, the essential ingredients for life as we know it.

Volatiles are fragile. During planetary formation, they can be stripped away by intense heat or stellar winds. Mercury, which formed very close to the Sun, lost most of its volatiles. Mars, which formed farther out, retained far more. This difference alone has had profound consequences for their evolutionary paths.

Without sufficient volatiles, a planet may never develop oceans, atmospheres, or the chemistry needed for life. But as the researchers point out, having too many volatiles can also be a problem.

Oxygen Fugacity and the Size of a Planet’s Core

This leads to the third factor: oxygen fugacity, a measure of how much oxygen is available during a planet’s formation. Oxygen fugacity determines whether iron remains in its pure metallic form or binds with oxygen to form iron oxides.

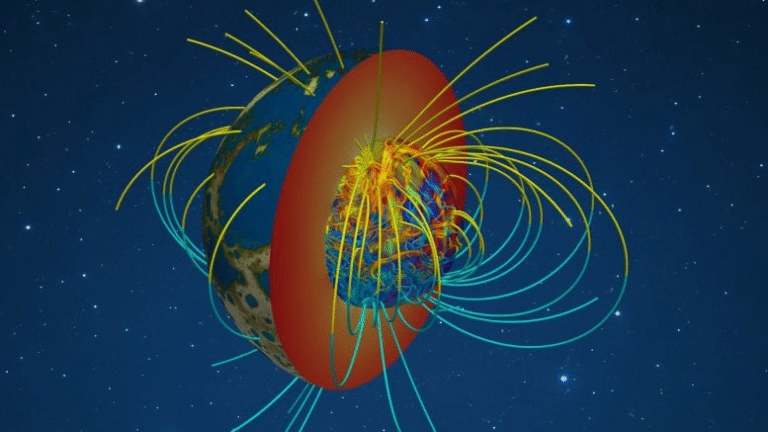

This distinction is crucial. Pure iron sinks to the planet’s core, creating a larger metallic core. Iron oxides remain in the mantle, resulting in a smaller core. Core size, in turn, controls the strength of a planet’s magnetic field.

A strong magnetic field acts as a protective shield, deflecting harmful solar radiation and preventing stellar winds from stripping away the atmosphere. Earth’s magnetic field has played a central role in preserving its atmosphere and surface water. Mars, with its small core and weak magnetic field, lost much of its atmosphere over time.

A New Kind of Goldilocks Balance

Interestingly, the study suggests that habitability depends on a delicate balance. A planet needs enough volatiles to support life, but not so many that oxygen prevents the formation of a large metallic core. This creates a new kind of Goldilocks Zone, not based on distance from a star, but on chemical balance.

Too few volatiles, and a planet ends up like Mercury: a massive core, strong magnetic field, but no atmosphere or life-supporting chemistry. Too many volatiles, and the planet resembles Mars: chemically rich but magnetically weak and exposed to radiation. Earth sits right in the middle, with a strong magnetic field and enough volatiles left over to sustain life for billions of years.

Heat Engines That Keep Planets Alive

The fourth factor highlighted in the study is a planet’s internal heat engine. Internal heat drives geological activity, including volcanism and plate tectonics. This heat comes from two main sources: radioactive decay and tidal heating.

Three radioactive elements are especially important: potassium, thorium, and uranium. Their decay releases heat over long timescales, keeping the mantle active. While uranium is difficult to measure directly, astronomers use europium as a proxy because it forms under similar stellar conditions.

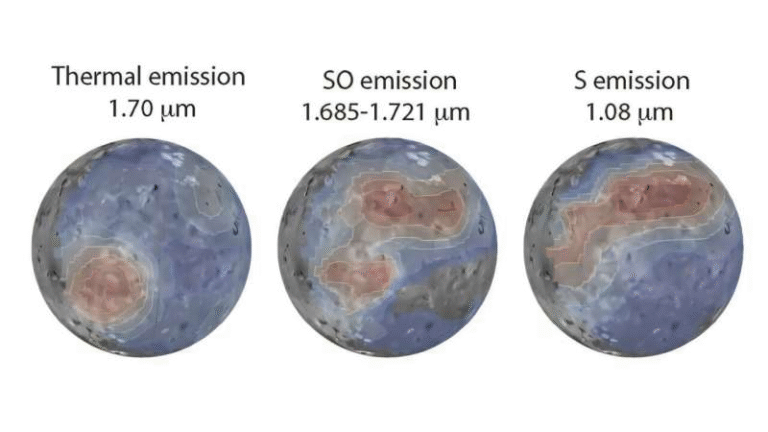

Tidal heating, seen in moons like Jupiter’s Io, can also keep a planet or moon geologically active by flexing its interior through gravitational interactions.

What Future Telescopes Will Look For

The Habitable Worlds Observatory is expected to measure many of these formation-related factors indirectly. By analyzing stellar spectra, scientists can infer volatile and radioactive element abundances. Using spectropolarimetry, HWO may detect planetary magnetic fields by observing how light interacts with them.

The telescope will also search for signs of active geology, sometimes described as volcanic breath, such as sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide in planetary atmospheres. These gases suggest ongoing volcanism and, by extension, plate tectonics.

Together, these observations would provide a far more comprehensive picture of habitability than orbital distance alone.

Expanding Our Understanding of Life in the Universe

This research reinforces a growing idea in astrobiology: habitability is a systems problem. It depends on chemistry, physics, geology, and time working together in just the right way. Life-friendly planets are not just in the right place; they are built the right way from the start.

While HWO is not expected to launch until the 2040s, this work is shaping how scientists think about what to look for when it finally does. Understanding planetary origins may be the key to answering one of humanity’s biggest questions: how common is life in the universe?

Research paper:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.16714