Why Scientists Think the First Alien Civilization We Detect Will Be Extremely Loud

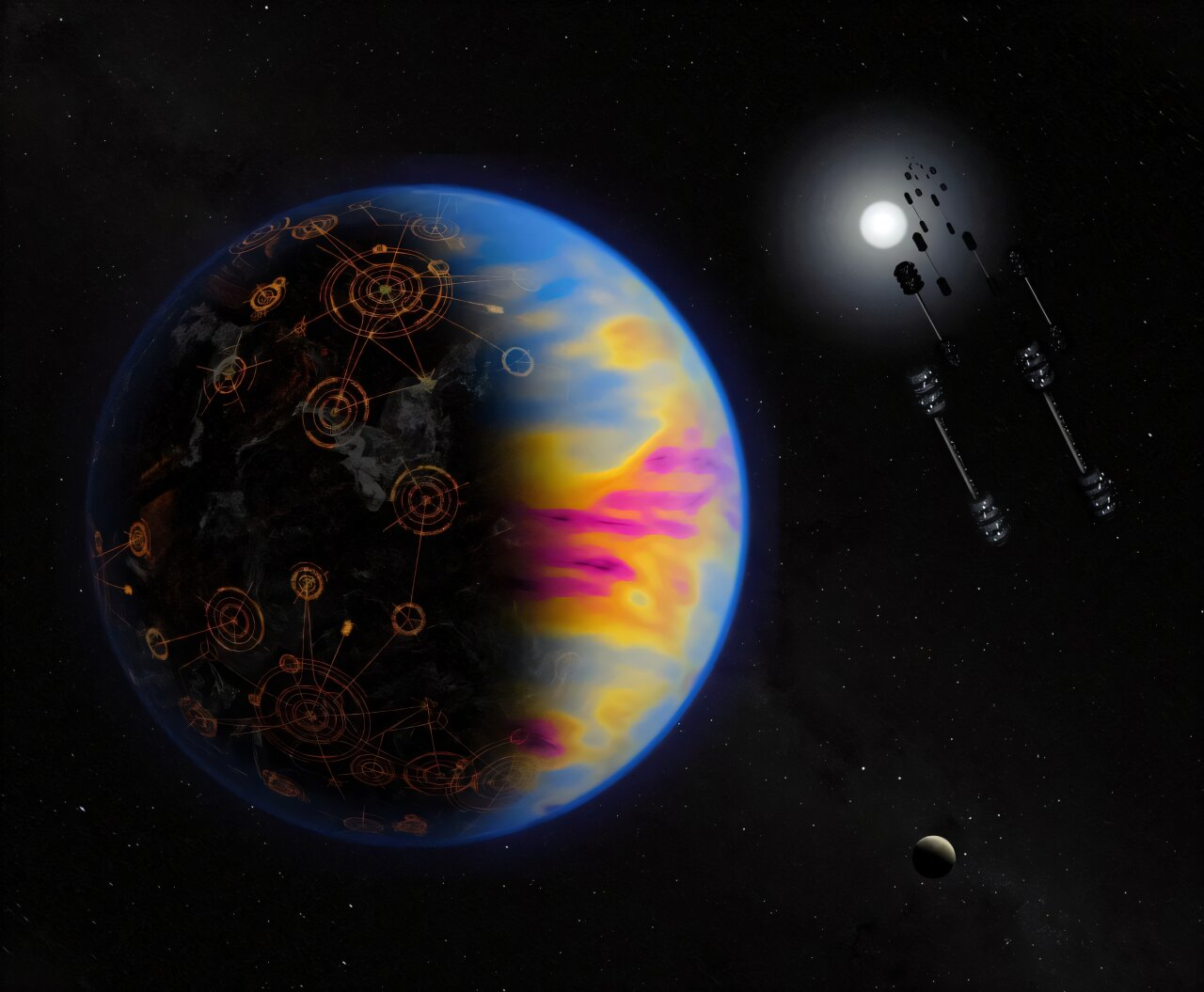

For decades, popular culture has shaped our expectations of alien contact. Movies and books often imagine dramatic invasions, benevolent cosmic saviors, or mysterious beings reaching out with carefully crafted messages. But new scientific thinking suggests something very different. According to recent research, the first alien civilization humanity detects is unlikely to be calm, subtle, or neatly organized. Instead, it will probably be extremely loud, highly unusual, and possibly in serious trouble.

This idea comes from a new research paper by astronomer David Kipping, a well-known figure in exoplanet science and the director of the Cool Worlds Lab at Columbia University. His work focuses on planets beyond our solar system, technosignatures, and how we might realistically detect extraterrestrial intelligence. In his latest study, Kipping introduces what he calls the Eschatian Hypothesis, a framework that challenges many assumptions about first contact with alien civilizations.

The Eschatian Hypothesis Explained

At the heart of Kipping’s argument is a simple but powerful observation: in astronomy, the first examples we detect of any new phenomenon are rarely typical. Instead, they tend to be the most extreme, dramatic, and easiest to observe. This is not because those objects are common, but because our instruments and methods are biased toward detecting things that stand out.

Kipping applies this idea to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. If intelligent civilizations exist elsewhere in the universe, the first one we discover is unlikely to be a quiet, stable society efficiently managing its energy. Rather, it will probably be an atypical civilization producing a very strong technosignature, one that is hard to miss.

The term “eschatian” comes from eschatology, which refers to the study of endings, final events, and collapse. In this context, the hypothesis suggests that the first alien civilization we detect may be in a transitory, unstable, or even terminal phase of its existence.

Why Astronomy Favors the Loud and Extreme

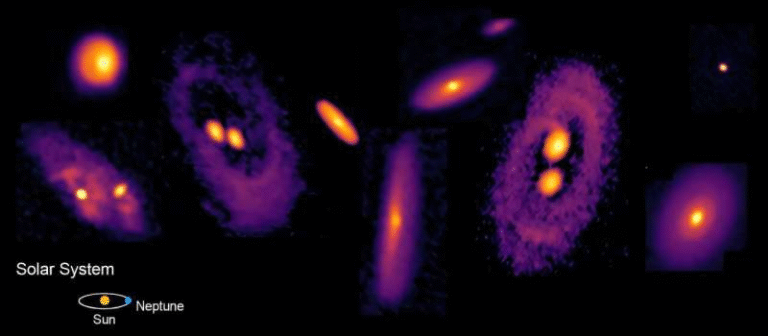

To understand why this idea makes sense, it helps to look at the history of astronomical discovery. When scientists first began detecting exoplanets in the early 1990s, the earliest discoveries were planets orbiting pulsars. Today, we know these systems are extremely rare. Out of more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets listed in the NASA Exoplanet Archive, fewer than ten orbit pulsars.

They were discovered first not because they were common, but because pulsars are extraordinarily precise cosmic clocks. Any planet orbiting them creates a noticeable disruption in their timing, making detection much easier.

The same bias applies to stars visible to the naked eye. Roughly one-third of the stars we can see without telescopes are giant stars, yet giant stars make up only a small fraction of all stars in the galaxy. Most stars are dim red dwarfs, including our nearest stellar neighbor, which remains invisible to the naked eye. Giants simply stand out because their observational signals are so strong.

Kipping argues that extraterrestrial civilizations should follow the same pattern. If we detect one, it will likely be because it produces a disproportionately large signal, not because it represents the average alien society.

What Does “Loud” Mean in This Context?

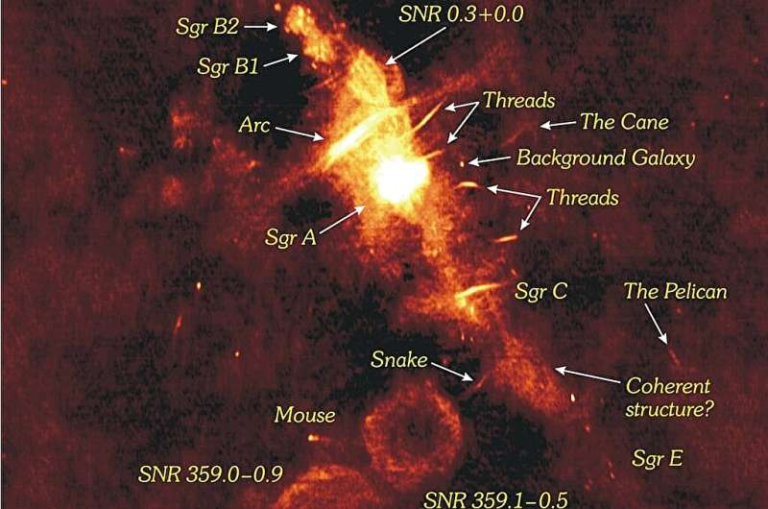

In the Eschatian Hypothesis, “loud” does not necessarily mean literal sound. Instead, it refers to technosignatures—observable signs of technology that can be detected across interstellar distances. These could include unusual electromagnetic emissions, large-scale atmospheric changes, or transient events that do not match known astrophysical processes.

One possibility is that a civilization in decline becomes loud as a byproduct of its instability. For example, industrial activity on Earth has significantly altered our atmosphere. Rising carbon dioxide levels, chemical pollutants, and rapid climate change could be detectable from afar. To an advanced extraterrestrial observer, Earth might already appear as a technologically active but environmentally stressed planet.

Another possibility is that a civilization intentionally produces a powerful signal as a desperate attempt to be noticed. Rather than a carefully encoded message, this could look more like an unmistakable beacon or anomalous burst that cuts through the cosmic noise.

Kipping has even speculated whether famous unexplained events like the Wow! signal detected in 1977 could fit into this framework. While there is no evidence linking that signal to alien technology, the hypothesis raises the idea that such events could represent a civilization approaching its own end.

Implications for the Search for Alien Life

The Eschatian Hypothesis has important consequences for how scientists search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Traditional SETI efforts have often focused on narrow targets, such as specific radio frequencies or signals resembling intentional communication. While valuable, this approach may miss the kinds of signals Kipping believes are most likely to be detected first.

Instead, the hypothesis favors wide-field, high-cadence surveys that continuously monitor large portions of the sky. These surveys are designed to detect transient events—sudden changes in brightness, spectrum, or motion that occur over short timescales.

Facilities such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory and long-running projects like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey already scan the sky repeatedly, generating massive datasets. While they are not built specifically for SETI, they are well suited to catching anomalous phenomena that cannot be easily explained by known astrophysics.

Kipping argues that rather than searching only for predefined technosignatures, scientists should prioritize agnostic anomaly detection. In other words, look for anything that appears strange, extreme, or out of place, and then investigate whether technology could be responsible.

Why Quiet Civilizations May Be Invisible

An important implication of this idea is that long-lived, stable civilizations might be very hard to detect. A society that has mastered efficient energy use, minimized waste, and achieved environmental balance could leave little trace visible across interstellar distances. Such civilizations may be abundant, but effectively invisible to us.

This perspective offers a new angle on the Fermi Paradox, the long-standing question of why we see no clear evidence of alien life despite the vastness of the universe. If most civilizations are quiet and only the loud, short-lived ones stand out, then the silence may not be surprising at all.

A Shift in Expectations About First Contact

The Eschatian Hypothesis does not suggest that alien civilizations are necessarily hostile or benevolent. Instead, it reframes first contact as something likely to be messy, rare, and unrepresentative. Humanity’s first confirmed detection of extraterrestrial intelligence may not be a conversation, an exchange of knowledge, or a dramatic arrival. It could simply be the observation of a powerful, puzzling signal that hints at a civilization under stress.

History shows that many astronomical “firsts” are extreme outliers rather than typical examples. If that pattern holds true for extraterrestrial intelligence, then our first glimpse of alien technology may tell us more about how civilizations end than how they thrive.

Research paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.09970