Young Galaxies Grow Up Fast as New Research Reveals Unexpected Chemical Maturity

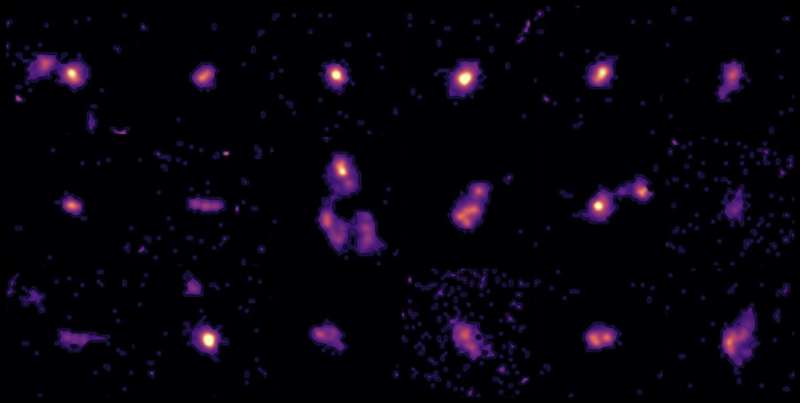

Astronomers have taken one of the most detailed looks ever at young galaxies in the early universe, and the results are forcing scientists to rethink how quickly galaxies can grow, mature, and enrich themselves with heavy elements. Using a powerful combination of space- and ground-based telescopes, researchers found that galaxies forming just one billion years after the Big Bang were already behaving more like cosmic teenagers than newborns.

The findings come from the ALPINE-CRISTAL-JWST Survey, a major international research effort that focused on 18 distant galaxies located about 12.5 billion light-years away. These galaxies existed during a critical era in cosmic history, when star formation across the universe was at its peak and galaxies were rapidly assembling their mass, structure, and chemistry.

A powerful trio of telescopes

To achieve this level of detail, astronomers combined observations collected over eight years from three of the world’s most advanced observatories: NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile. Additional data from ground-based telescopes helped measure key properties such as the total mass of stars in each galaxy.

What makes this survey special is its multiwavelength approach. Different parts of a galaxy emit light at different wavelengths, so by observing everything from ultraviolet and optical light to radio waves, scientists were able to study stars, gas, dust, and metals all at once. This is also the first survey to spatially resolve galaxies at such extreme distances, meaning researchers could examine different regions inside each galaxy instead of seeing them as blurry points of light.

Galaxies that matured faster than expected

One of the most striking discoveries is that these early galaxies are far more chemically mature than astronomers predicted. Chemical maturity in astronomy refers to the presence of heavy elements, known as metals, such as carbon and oxygen. These elements are created inside stars and spread through galaxies when stars die.

The surprise here is timing. Conventional models suggested that there simply hadn’t been enough time for early galaxies to produce large amounts of metals. Yet the ALPINE-CRISTAL-JWST galaxies show metal abundances comparable to much older galaxies, even though the universe was less than a billion years old at the time.

This means that star formation, stellar evolution, and chemical recycling were happening extremely efficiently and very quickly. In simple terms, these galaxies were growing up much faster than anyone expected.

Star formation in full swing

The galaxies observed in this survey were in an intense phase of star formation. By using JWST’s ability to detect the hydrogen alpha emission line, astronomers traced regions of hot, ionized gas, which is a clear indicator of ongoing star birth. These observations allowed researchers to see where stars were forming inside the galaxies and how those regions were distributed.

Many of the galaxies show signs of interactions and mergers, with two or even three galaxies in the process of colliding and combining. These interactions are known to trigger bursts of star formation and can help explain the rapid buildup of stars and metals.

Early structure and rotating disks

The new findings build on earlier results from the parent ALPINE survey, which studied a larger sample of 118 galaxies. That earlier work revealed that many young galaxies already had rotating disks, a structural feature similar to what we see in spiral galaxies like the Milky Way.

The new study shows that some galaxies were not only structurally developed but also chemically evolved at the same time. This combination suggests that galaxy formation in the early universe was far more advanced and organized than previously assumed.

Supermassive black holes already feeding

Another major result involves supermassive black holes. Nearly half of the galaxies in the sample show evidence that their central black holes were actively accreting material, meaning they were growing rapidly.

This finding supports the idea that galaxy growth and black hole growth are closely linked, even in the early universe. The fact that black holes were already feeding at such early times adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of how galaxies evolve.

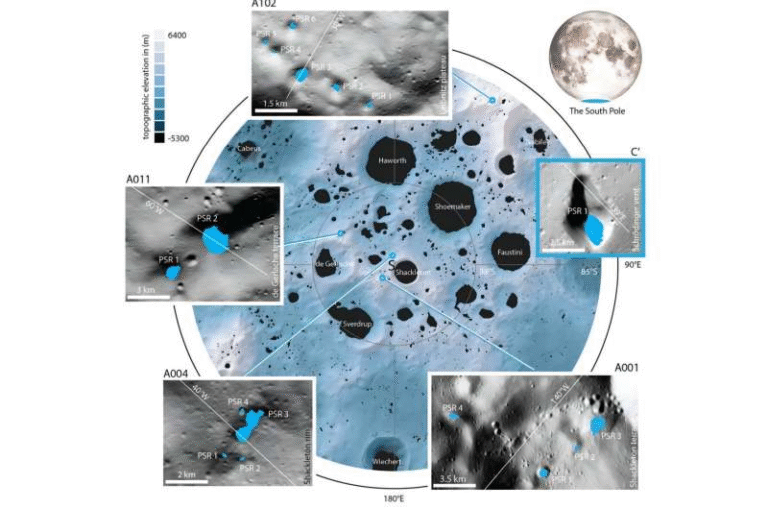

Enriched gas beyond the galaxies

The study didn’t stop at the galaxies themselves. Astronomers also examined the circumgalactic medium, the vast halo of gas surrounding each galaxy. Surprisingly, this surrounding gas was also found to be chemically enriched, with metals extending more than 30,000 light-years from the galaxy centers.

Even more interesting, the metal distribution was relatively flat, meaning heavy elements were spread evenly rather than concentrated in the center. This suggests strong outflows, mixing processes, and gas circulation, likely driven by intense star formation and galactic interactions.

Why metals matter in the universe

In astronomy, metals play a crucial role. Elements like carbon and oxygen are essential for forming rocky planets, complex chemistry, and ultimately life. Understanding when and how these elements formed helps scientists trace the origins of planetary systems, including our own.

Seeing such high metal content so early in cosmic history means the building blocks for planets may have been available much earlier than previously believed.

The role of JWST in rewriting cosmic history

The James Webb Space Telescope has been a game changer for studies like this. Its ability to perform integral field unit (IFU) spectroscopy allows astronomers to capture both images and spectra across entire galaxies at once. This makes it possible to map chemical composition, gas motion, and star formation in extraordinary detail, even at extreme distances.

Combined with ALMA’s sensitivity to cold gas and dust, researchers now have a much more complete picture of how early galaxies functioned.

What comes next for this research

The team plans to combine these observations with cosmological simulations, including advanced models developed by theoretical astrophysicists at Caltech. By comparing real galaxies with simulated ones, scientists hope to better understand the physical processes driving rapid star formation, metal production, and dust creation in the early universe.

Ultimately, this work helps bridge the gap between the first galaxies and more familiar systems like the Milky Way, offering new insight into how galaxies — and the ingredients for planets and life — came to be.

The results were presented at the 247th meeting of the American Astronomical Society on January 6, 2026, and involved an international collaboration of more than 50 scientists from over 15 institutions. Several companion studies are also expanding on these findings using additional JWST data.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ae0928