A Simple Temperature Trick Could Finally Solve the Dendrite Problem in Solid-State Batteries

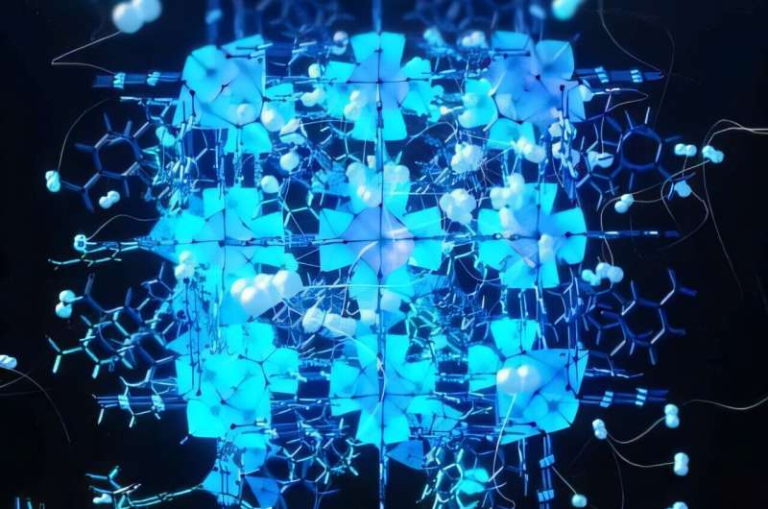

Solid-state batteries are often described as the future of energy storage, especially for electric vehicles, grid storage, and high-performance electronics. They promise faster charging, higher energy density, and improved safety compared to today’s lithium-ion batteries that rely on liquid electrolytes. Yet despite years of research, one stubborn issue has consistently stood in the way of large-scale adoption: lithium dendrites.

Now, engineers at Brown University have proposed a surprisingly straightforward solution. Instead of inventing new materials or adding complex chemical layers, they show that temperature-induced mechanical stress can significantly suppress dendrite growth. Their findings, published in the journal Joule, suggest that a carefully controlled temperature gradient could dramatically improve the charging performance and reliability of solid-state lithium batteries.

Understanding the Dendrite Problem in Solid-State Batteries

To understand why this research matters, it helps to first understand the problem it addresses. Dendrites are tiny, needle-like filaments of lithium metal that form during battery charging, especially at high currents. Over time, these filaments can grow through the electrolyte—the material that separates the battery’s anode and cathode.

When dendrites reach the opposite electrode, they cause internal short circuits, which can permanently damage the battery or even lead to catastrophic failure. While solid electrolytes are theoretically better at blocking dendrites than liquid ones, real-world experiments have shown that dendrites can still penetrate solid materials, especially under fast-charging conditions.

This issue has been one of the biggest barriers preventing solid-state batteries from reaching their full potential.

A Temperature-Based Mechanical Solution

The Brown University research team took a different approach. Instead of focusing on chemistry alone, they explored how mechanical stress inside the electrolyte affects dendrite formation.

Their idea was simple: apply a temperature gradient across the solid electrolyte. One side of the electrolyte is heated, while the other side is cooled. This temperature difference causes uneven thermal expansion. The warmer side wants to expand more, but the cooler side restricts it, creating compressive mechanical stress within the material.

This compression turns out to be extremely effective at suppressing dendrite growth.

With a temperature difference of just 20 degrees Celsius, the researchers achieved a threefold increase in the battery’s critical current density—the maximum charging current the battery can handle before dendrites begin to form.

How the Experiment Was Conducted

The team tested battery cells using lithium metal electrodes separated by a solid electrolyte known as LLZTO (Li₆.₄La₃Zr₁.₅Ta₀.₅O₁₂). This garnet-type electrolyte is widely studied because of its high ionic conductivity, but it is also well known for being vulnerable to dendrite penetration at high charging rates.

To create the temperature gradient, the researchers used a ceramic heating ring on one side of the electrolyte and a copper heat sink on the opposite side. This setup allowed them to precisely control the temperature difference and the resulting mechanical stress.

Measurements confirmed that the temperature gradient produced a compressive stress field inside the electrolyte. Electrochemical testing then showed that this stress significantly delayed or prevented dendrite penetration, even under conditions that would normally cause failure.

Why Compression Makes Such a Big Difference

Lithium dendrites tend to grow along paths of least resistance, often exploiting microscopic cracks, pores, or grain boundaries within solid electrolytes. Compressive stress helps by closing these pathways and making it physically harder for dendrites to propagate.

In simple terms, the electrolyte is being gently squeezed, and that squeezing makes it far less welcoming for dendrites to push through. This insight reinforces a growing understanding in battery science: mechanical properties matter just as much as chemical ones.

Implications for Real-World Battery Design

One of the most exciting aspects of this research is its practical potential. Batteries already generate heat during normal operation, and modern battery packs rely on thermal management systems to control temperatures for safety and performance.

The researchers suggest that future solid-state battery designs could intentionally align thermal architecture to create beneficial temperature gradients during charging. Instead of fighting heat everywhere, engineers might use it strategically to enhance performance and longevity.

Importantly, this approach does not require exotic materials or entirely new manufacturing processes, which could make it easier to scale for commercial use.

How This Fits into the Bigger Picture of Battery Research

The dendrite problem has inspired a wide range of proposed solutions over the years. These include:

- Interface coatings to smooth current distribution

- Material doping to strengthen grain boundaries

- Higher stack pressure applied externally to the battery

- Composite electrolytes that combine polymers and ceramics

The Brown University study adds strong experimental evidence that internal compressive stress, even when generated indirectly through temperature differences, can play a decisive role in dendrite suppression.

Rather than competing with other strategies, this method could complement existing approaches, leading to multi-layered defenses against dendrite formation.

Why Solid-State Batteries Still Matter So Much

Despite their challenges, solid-state batteries remain a key focus for researchers and manufacturers alike. Compared to conventional lithium-ion batteries, they offer several major advantages:

- Improved safety due to non-flammable solid electrolytes

- Higher energy density, enabling longer driving ranges for EVs

- Faster charging potential without liquid electrolyte limitations

- Better thermal stability at high temperatures

If the dendrite issue can be reliably controlled, solid-state batteries could fundamentally reshape the energy storage landscape.

What Comes Next for This Research

The Brown team sees this study as a validation of earlier theoretical work and a foundation for further optimization. Future research will focus on identifying ideal material properties, electrolyte thicknesses, and loading conditions that maximize the benefits of thermally induced compression.

There is also interest in exploring how this approach behaves under long-term cycling, real-world temperature fluctuations, and full battery pack configurations.

A Small Change with Big Potential

What makes this research especially compelling is its simplicity. A modest temperature gradient—something batteries already experience—can lead to dramatic improvements in charging performance and reliability.

As solid-state batteries move closer to commercialization, insights like this could make the difference between laboratory promise and real-world success.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joule.2025.102232