Artificial Tendons Are Giving Muscle-Powered Robots a Serious Performance Boost

Researchers at MIT have taken a major step forward in the world of biohybrid robotics by developing artificial tendons that dramatically improve how muscle-powered robots move, grip, and apply force. By borrowing a key idea from human biology—how muscles connect to bones through tendons—the team has solved several long-standing problems that limited the strength, speed, and durability of robots powered by living muscle tissue.

Biohybrid robots, which combine lab-grown muscle with synthetic mechanical structures, have been around for a little over a decade. These systems are fascinating because muscle is an incredibly efficient natural actuator. Each muscle cell generates force on its own, making muscle especially attractive for small-scale robots, where traditional motors often fail due to size and physics constraints. Muscle tissue also has unique advantages: it can grow stronger with use, repair itself when damaged, and operate efficiently at tiny scales.

Despite these strengths, most muscle-powered robots so far have suffered from limited motion and weak force output. The new research, published in the journal Advanced Science, shows how artificial tendons can change that equation entirely.

Why Muscle-Powered Robots Needed a Better Connection

In earlier biohybrid designs, engineers typically grew a strip of muscle and attached both ends directly to a robotic skeleton. This setup is similar to looping a rubber band around two rigid posts. While simple, the approach has serious drawbacks.

Muscle tissue is soft and fragile compared to rigid robotic materials. When directly attached, much of the muscle’s mass ends up being wasted on anchoring rather than generating movement. The stiffness mismatch can cause muscle to tear, detach, or fail prematurely, and only the central region of the muscle usually contributes to useful work. As a result, force output remains low, and performance degrades quickly.

In the human body, this problem is solved elegantly with tendons. Tendons sit between muscle and bone, with stiffness levels that fall somewhere in between. They efficiently transmit force, reduce strain on muscle tissue, and allow powerful, controlled motion. The MIT team decided to replicate this idea using engineered materials.

Introducing Artificial Tendons Made from Hydrogel

The researchers developed artificial tendons using a tough yet flexible hydrogel, a polymer-based material known for its stretchability and strength. These hydrogels were developed in collaboration with MIT professor Xuanhe Zhao, whose lab specializes in hydrogels that can strongly bond to both biological tissue and synthetic materials.

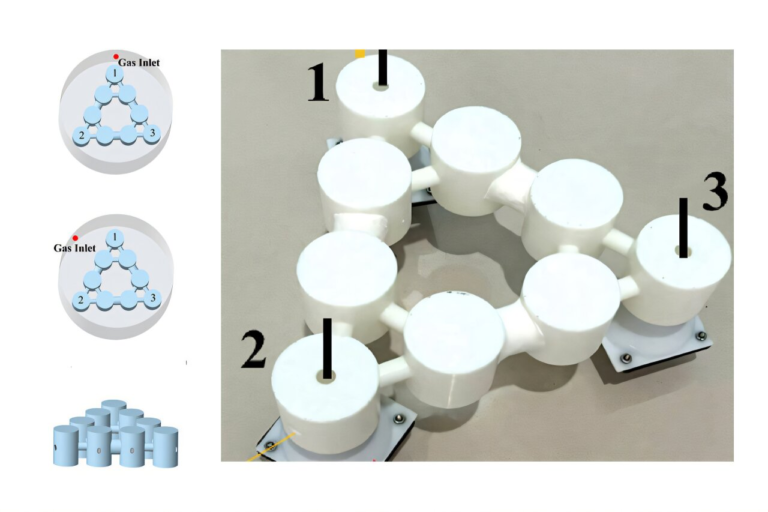

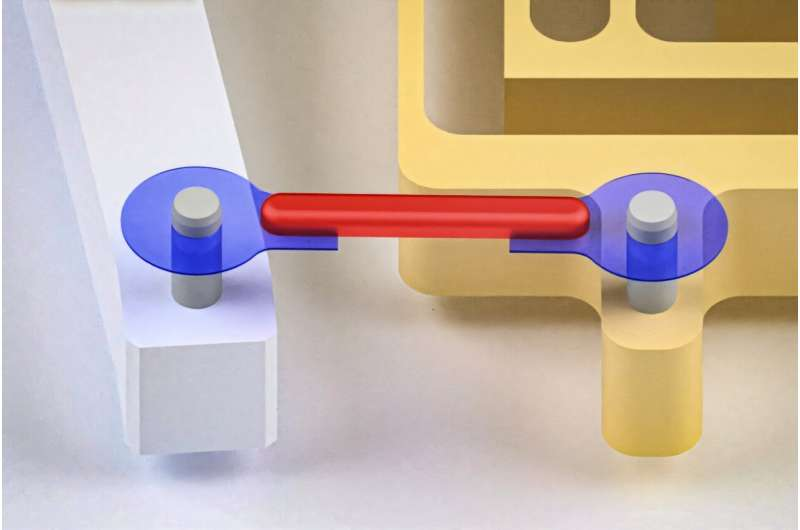

To create a functional muscle-tendon unit, the team attached a thin hydrogel tendon to each end of a small piece of lab-grown muscle. These tendon ends were then connected to the fingers of a robotic gripper, forming a modular system that closely resembles natural muscle-tendon-bone architecture.

Before building the physical system, the researchers modeled the setup mathematically. They treated the muscle, tendons, and robotic skeleton as a system of interconnected springs. Since the stiffness of muscle and the gripper skeleton were already known, the model allowed them to calculate the ideal tendon stiffness needed to achieve efficient motion without damaging the muscle.

Using this data, they produced hydrogel tendons with precisely tuned mechanical properties and etched them into thin, cable-like structures suitable for robotic use.

Dramatic Gains in Speed, Strength, and Durability

When the muscle in the center of the system was electrically stimulated to contract, the artificial tendons transmitted that force directly to the robotic gripper. The results were striking.

Compared to a gripper powered by muscle alone, the tendon-enhanced design operated three times faster and generated 30 times more force. Just as importantly, the system remained stable and functional for more than 7,000 contraction cycles, demonstrating impressive durability.

Another key improvement was efficiency. By adding artificial tendons, the researchers increased the robot’s power-to-weight ratio by 11 times. This means far less muscle tissue was needed to achieve the same mechanical output, reducing biological waste and making designs more compact and practical.

The tendons also prevented muscle damage. Instead of tearing under resistance, the muscle could safely transmit its force through the tendon, allowing it to move structures that would previously have been too stiff or heavy.

A Modular Building Block for Biohybrid Robotics

One of the most important aspects of this work is modularity. The artificial tendons act as interchangeable connectors between muscle actuators and robotic skeletons. This makes them a versatile building block that can be reused across many designs, rather than custom-engineering a new attachment method for every robot.

This modular approach could significantly speed up development in the field. Muscle-tendon units could be integrated into crawlers, walkers, swimmers, grippers, or even microscale devices, all using the same fundamental connection strategy.

The robotic gripper used in the study was designed by MIT professor Martin Culpepper, an expert in precision machine design. Its success demonstrates that artificial tendons can work effectively with high-precision mechanical systems, not just experimental lab prototypes.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

Biohybrid robots are still largely confined to research environments, but this work brings them closer to real-world applications. Muscle-powered robots could one day be deployed in environments that are too dangerous or inaccessible for humans, such as disaster zones, deep-sea locations, or space exploration scenarios.

Because muscle tissue can adapt, grow stronger, and heal, these robots could continue functioning even when damaged or exposed to unpredictable conditions. Researchers also see potential for medical applications, including microscale surgical tools capable of performing delicate procedures inside the human body.

Beyond robotics, the system offers a new platform for studying muscle physiology, force transmission, fatigue, and injury mechanisms in controlled settings. Insights gained from these robotic models could eventually inform both biomedical research and rehabilitation science.

The Role of Hydrogels in Soft Robotics

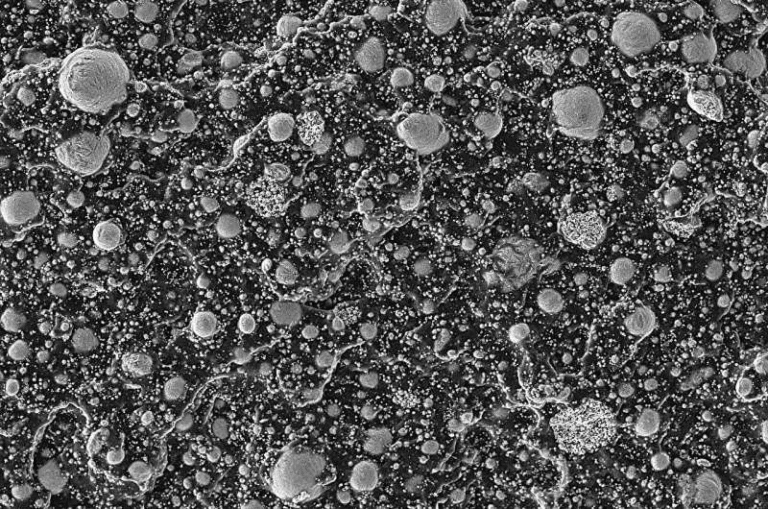

Hydrogels are increasingly important in soft robotics, where flexibility, stretchability, and biocompatibility are essential. Unlike rigid plastics or metals, hydrogels can deform without breaking and bond well to living tissue.

In this study, hydrogels served as the perfect middle ground between soft muscle and rigid skeleton. Their tunable mechanical properties allowed researchers to precisely match biological requirements, highlighting why hydrogels are becoming a cornerstone material in biohybrid and soft robotic systems.

What Comes Next for Muscle-Powered Robots

With artificial tendons now proven to boost performance, the MIT team is working on additional components to make biohybrid robots more robust. One focus is developing skin-like protective casings that can shield living tissue from dehydration, contamination, and mechanical damage outside the lab.

Together, artificial tendons, protective layers, and modular designs could pave the way for biohybrid robots that operate reliably in real-world environments, rather than just controlled experimental setups.

This research marks an important milestone in merging biology with engineering, showing that sometimes the smartest solutions come from copying what nature already does best.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202512680