Biodegradable Electronics Might Be Creating Microplastics Instead of Solving E-Waste

The idea of biodegradable electronics sounds almost too good to be true. Devices that naturally dissolve at the end of their lifespan promise a future where electronic waste no longer piles up in landfills or leaks toxins into the environment. But new research from Northeastern University suggests this green solution may come with a hidden and troubling downside. Instead of harmlessly disappearing, some materials used in these so-called transient electronics may be breaking down into microplastics, raising serious questions about how environmentally safe these technologies really are.

What Are Transient or Biodegradable Electronics?

Transient electronics are devices specifically designed to degrade after a certain period of use. Unlike traditional electronics, which persist for decades, these systems are intended to dissolve in soil or water once their job is done. They are especially attractive for applications such as medical implants, temporary sensors, edible electronics, and dissolvable surgical devices, where long-term durability is not needed.

Over the past decade, interest in these devices has grown rapidly. Researchers and manufacturers alike have viewed them as a promising way to reduce electronic waste, one of the fastest-growing pollution problems globally. However, as this new study highlights, the story doesn’t end once a device appears to dissolve.

The Research That Raised the Alarm

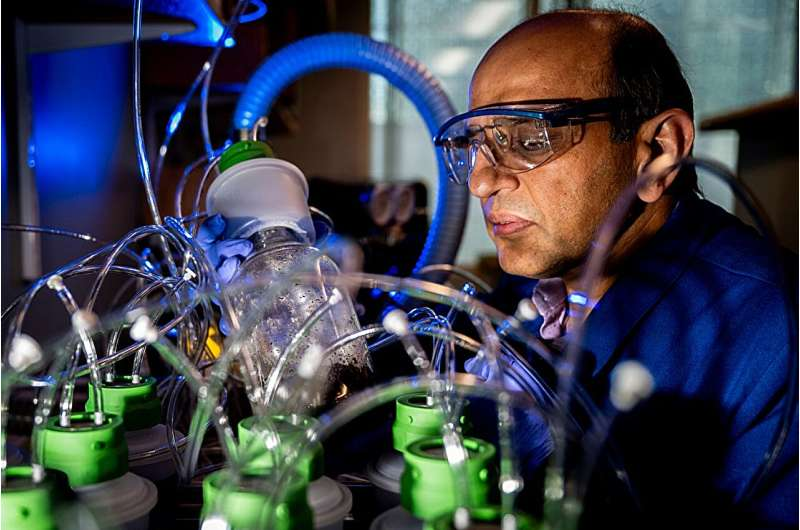

The findings come from a study led by Ravinder Dahiya, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern University, along with Sofia Sandhu, a former postdoctoral researcher in his lab. Their work was published in npj Flexible Electronics in 2025 and focused on what actually happens to biodegradable electronics at the end of their life.

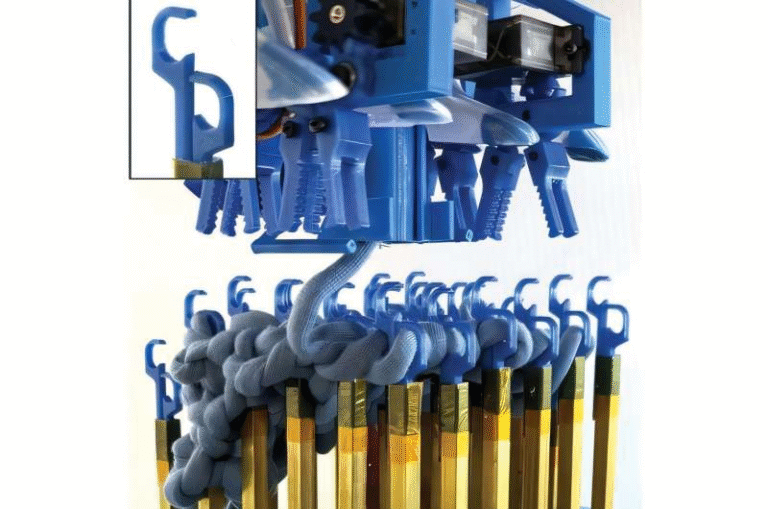

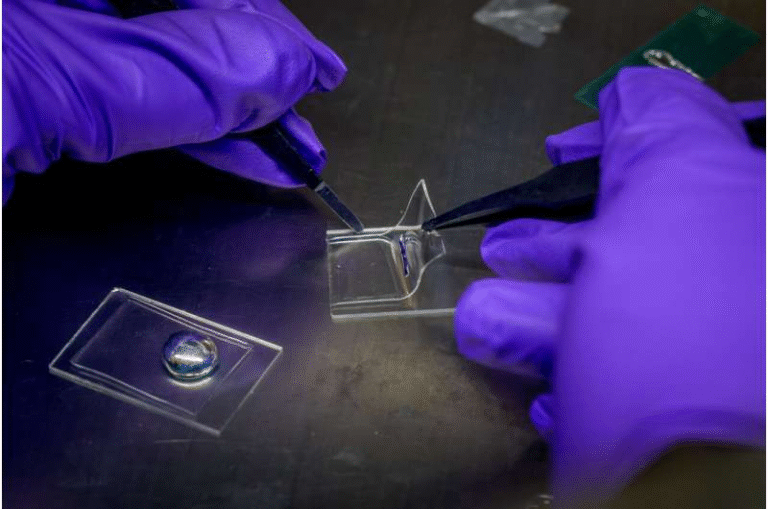

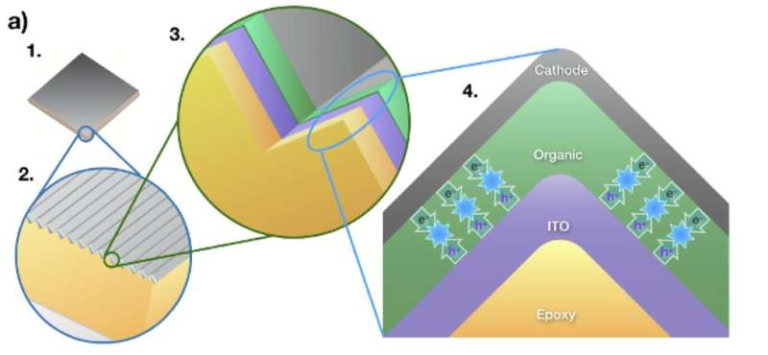

The researchers examined two specific transient electronic devices: a partly degradable pressure sensor and a fully degradable photodetector. Instead of simply observing whether these devices disappeared visually, the team analyzed what remained behind after degradation, paying close attention to chemical byproducts and material persistence.

What they found was concerning. Some materials that are widely assumed to be biodegradable may not fully break down into harmless components.

PEDOT:PSS and the Microplastic Problem

One of the biggest red flags identified in the study involves a polymer called PEDOT:PSS. This conductive polymer is commonly used in flexible and biodegradable electronics, particularly in medical and bioelectronic applications, because it performs well electrically and can be processed easily.

However, the research showed that PEDOT:PSS can persist in soil for more than eight years. Instead of fully degrading, it can fragment into microplastic particles during the breakdown process. These tiny plastic fragments are small enough to remain in soil, potentially enter water systems, and even make their way into living organisms.

This finding challenges the assumption that all materials used in biodegradable electronics are inherently safe. A device may appear to dissolve, but its chemical footprint can linger far longer than expected.

Why Material Choice Matters So Much

The study highlights that not all biodegradable materials behave the same way. Natural polymers such as cellulose and silk fibroin were found to degrade more efficiently and produce byproducts that are generally considered environmentally benign. These materials break down faster and are less likely to leave persistent residues behind.

In contrast, certain synthetic polymers may degrade slowly or incompletely, creating long-term environmental risks. This difference makes material selection a critical factor in designing truly sustainable electronics.

The researchers emphasized that electronics are often discarded directly into soil at the end of their life. If the degradation process introduces harmful substances or microplastics into the environment, the damage could be long-lasting and difficult to reverse.

Ongoing Studies on Degradation and Soil Impact

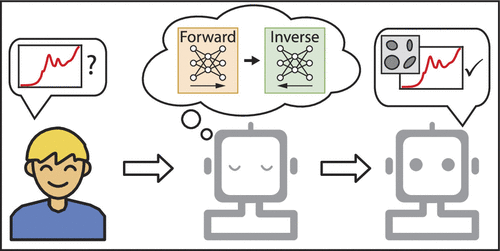

To better understand these risks, further research is already underway. Monika Swami, a doctoral student in Dahiya’s lab, is leading a new study focused on how polymer-based electronics degrade in soil. Her work measures carbon dioxide production during degradation, which helps scientists estimate how quickly materials break down and how complete the process really is.

The team is currently conducting six-month degradation tests, analyzing how long materials take to fully degrade and how much CO₂ they release. These measurements provide insight into whether a material truly biodegrades or merely fragments into smaller, potentially harmful pieces.

A Growing Market With Growing Concerns

Despite these challenges, the market for biodegradable electronic materials continues to expand. According to Grand View Research, the global biodegradable electronics polymers market was valued at $126.47 million in 2024 and is projected to grow to $246 million by 2033. This growth is driven largely by demand for medical devices, wearable sensors, and temporary electronics.

However, the study suggests that rapid commercialization without careful material evaluation could lead to unintended environmental consequences. Replacing traditional e-waste with microplastic pollution is not the sustainable future researchers are aiming for.

Manufacturing Is Part of the Environmental Equation

The environmental impact of electronics doesn’t begin or end with degradation. Manufacturing processes also play a significant role. Modern electronics production is highly resource-intensive and largely follows a linear model: make, use, dispose.

For example, producing a single silicon wafer, a key component in computer chips, can require up to 6,000 liters of water, along with a mixture of hazardous chemicals. With millions of wafers processed daily worldwide, the resulting wastewater and resource consumption are enormous.

This issue is made worse by global water scarcity. According to the World Economic Forum, around 40% of semiconductor manufacturing facilities are located in regions expected to face severe water stress by 2030. Any technology that increases resource use without addressing sustainability adds pressure to an already strained system.

Moving Toward Truly Sustainable Electronics

The long-term goal outlined by the researchers is to move toward a circular electronics ecosystem. In such a system, materials are reused, repurposed, or safely returned to the environment without causing harm. Ideally, future electronic devices would biodegrade into substances that enrich soil or safely dissolve in water, eliminating the need for specialized e-waste handling altogether.

Achieving this vision requires not just new device designs, but a deeper understanding of material chemistry, degradation pathways, and environmental interactions. It also calls for stricter standards to define what “biodegradable” truly means in the context of electronics.

Why This Research Matters

This study serves as an important reminder that green technology must be examined closely, not just at the surface level. A device disappearing from sight does not guarantee it has disappeared from the environment. The formation of microplastics from biodegradable electronics represents a subtle but potentially serious threat that deserves attention before these technologies become widespread.

As research continues, the focus will likely shift toward developing safer polymers, improving testing methods, and rethinking how sustainability is measured in electronics design. Biodegradable electronics still hold promise, but only if their full life cycle is understood and responsibly managed.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41528-025-00411-w