Grasshopper Wings Inspire a New Generation of Energy-Efficient Gliding Robots

A team of engineers and biologists from Princeton University and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has turned an everyday insect into a source of serious engineering insight. By closely studying how grasshoppers glide through the air, the researchers have developed new ideas for designing small, untethered gliding robots that can travel efficiently while using very little energy.

The collaboration began in a surprisingly simple way: researchers chasing grasshoppers across a hot parking lot. That informal start eventually led to a detailed scientific investigation into the hindwings of the American grasshopper, Schistocerca americana, and how their structure supports gliding flight. The findings were published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, and they offer both engineering and biological insights.

A Collaboration Between Engineering and Entomology

The study brought together experts from two different fields. Aimy Wissa, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton, worked with Marianne Alleyne, a professor of entomology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Alleyne’s laboratory frequently uses insects as model organisms to uncover traits that could be useful in engineering design.

The team was particularly interested in grasshoppers because of their ability to glide long distances with minimal energy expenditure. Unlike birds or flapping drones, grasshoppers can deploy their wings and coast through the air, relying on aerodynamic lift rather than constant muscle power.

Grasshoppers have two pairs of wings. The forewings are leathery and mainly act as protective covers. The real stars are the large, membranous hindwings, which can fold neatly when not in use and spread wide during flight. These hindwings are responsible for both flapping and gliding.

From an engineering perspective, gliding is especially attractive. Producing thrust through flapping requires significant energy, while gliding allows an organism—or a robot—to conserve power by simply maintaining lift.

The Mystery of Corrugated Wings

One of the most intriguing aspects of grasshopper hindwings is that they are not flat when fully deployed. Instead, they have a corrugated structure, with ridges and grooves running across the wing surface.

This raised an important question: is corrugation helpful, harmful, or simply a byproduct of the need to fold the wings? From a biological standpoint, corrugation could be neutral or structural. From an engineering standpoint, it might influence airflow, lift, and stability.

To find out, the researchers combined biological observation with mechanical testing. This kind of collaboration allowed them to move beyond speculation and directly measure how different wing features affect gliding performance.

CT Scans, 3D Printing, and Experimental Gliders

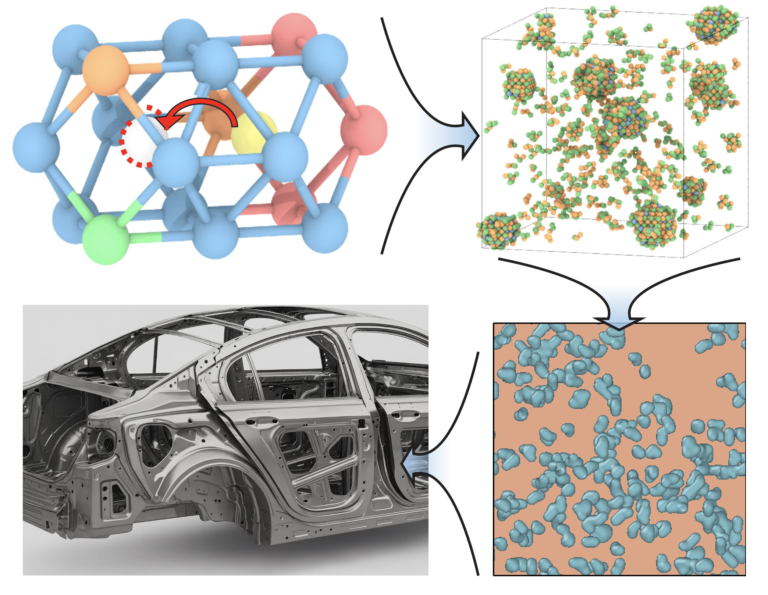

The team began by using CT scanning technology to capture highly detailed, three-dimensional images of real grasshopper wings. CT scans use X-rays and computational reconstruction to reveal internal and external geometry with great precision.

Using this data, the researchers created 3D-printed model wings that isolated specific features of the grasshopper hindwing. Some models emphasized corrugation, others focused on overall wing shape, and some tested variations in surface curvature.

These wings were then mounted on small experimental gliders. The gliders were tested in two main ways:

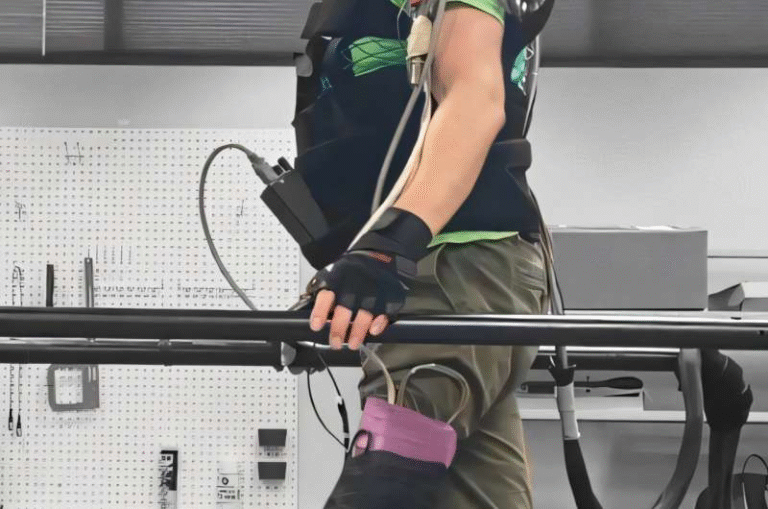

- In a water chamber, where fluid dynamics could be observed and measured in a controlled environment.

- In real-world launch tests across the Princeton Robotics Laboratory, where the team analyzed glide distance, stability, and overall aerodynamic performance.

This dual testing approach allowed the researchers to validate their findings across different conditions.

What the Experiments Revealed

The results were both clear and surprising. While corrugated wings did contribute to lift, the best-performing gliders were actually smooth, not corrugated. Smooth wings consistently showed better overall gliding efficiency.

This does not mean corrugation is useless. Instead, it suggests that corrugation may serve multiple functions in real grasshopper wings. One likely role is enabling compact folding, which is essential for insects that need to protect their wings when jumping or walking. Corrugation may also provide structural stiffness without adding much weight.

For engineering purposes, however, the study showed that simply copying corrugation does not automatically lead to better gliding performance. The challenge now is to combine the foldability advantages of corrugated wings with the aerodynamic efficiency of smooth surfaces.

Implications for Robotic Design

The findings have important implications for the design of small flying robots, especially those that need to operate without tethers or frequent battery recharging. Many current micro-air vehicles rely heavily on flapping, which drains power quickly.

By incorporating gliding as a major mode of locomotion, future robots could:

- Extend flight time

- Reduce battery size and weight

- Alternate between powered flight and passive gliding, depending on the task

This kind of hybrid approach mirrors how grasshoppers and other insects use energy efficiently in nature.

Engineering Helping Biology, Too

An interesting outcome of the project is that the tools developed for engineering may now help answer biological questions. Alleyne has expressed interest in using the prototype wings and launch systems to further study insect wing morphology.

This highlights a two-way relationship. Biology inspires engineering, and engineering tools allow scientists to test biological hypotheses in controlled, repeatable ways. In this case, artificial gliders are helping researchers understand why insects evolved certain wing features in the first place.

Extra Context: Why Insect Wings Matter in Engineering

Insect wings have long fascinated engineers because they operate in a flight regime that is very different from airplanes. At small scales, air behaves more like a thick fluid, and subtle changes in shape can have big effects on lift and drag.

Studying insects like grasshoppers is especially useful because they use multiple modes of movement. Grasshoppers can jump, flap, and glide, making them ideal models for multi-modal robots that need to navigate complex environments.

Research like this also contributes to broader fields such as biomimicry, aerodynamics at low Reynolds numbers, and lightweight structural design. Even insights that do not directly translate into robots can influence how engineers think about materials, folding mechanisms, and energy efficiency.

Looking Ahead

The research team plans to continue exploring how corrugation can be integrated into wings that still glide efficiently. Understanding how real grasshoppers deploy and retract their wings could also lead to autonomous folding mechanisms in robots.

Ultimately, this work shows how careful observation of nature, combined with modern tools like CT scanning and 3D printing, can lead to practical engineering advances. A simple insect, studied closely, may help shape the future of small flying machines.

Research paper:

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2025.0117