How Small Optical Computers Can Get and Why New Scaling Laws Change the Future of Light-Based Computing

Optical computing has long been talked about as a promising alternative to traditional electronic computing, mainly because light can process information at incredible speeds while consuming far less energy than moving electrons through wires. But there has always been a major practical question hanging over the field: how small can an optical computer actually be? A new study from researchers at Cornell University finally tackles this question head-on, offering clear theoretical limits, practical design strategies, and some surprisingly optimistic answers.

The research, published in Nature Communications in 2025, explores the idea of spatial complexity in optical computing. In simple terms, spatial complexity describes how much physical space an optical system needs in order to perform a given computational task. Just like software algorithms require time and memory to run, optical computers require physical room for light waves to travel, interact, and perform calculations. Understanding this relationship between task complexity and physical size is critical if optical computing is ever going to move beyond lab-scale experiments and into real-world applications.

Why Size Has Always Been a Problem for Optical Computing

One of the biggest challenges in optical computing comes from a basic physical fact: photons are much harder to confine than electrons. In electronic computers, transistors and circuits can be packed extremely densely on silicon chips. Light, on the other hand, naturally spreads out as it propagates. If an optical system needs too much space to perform even moderately complex tasks, it becomes impractical very quickly.

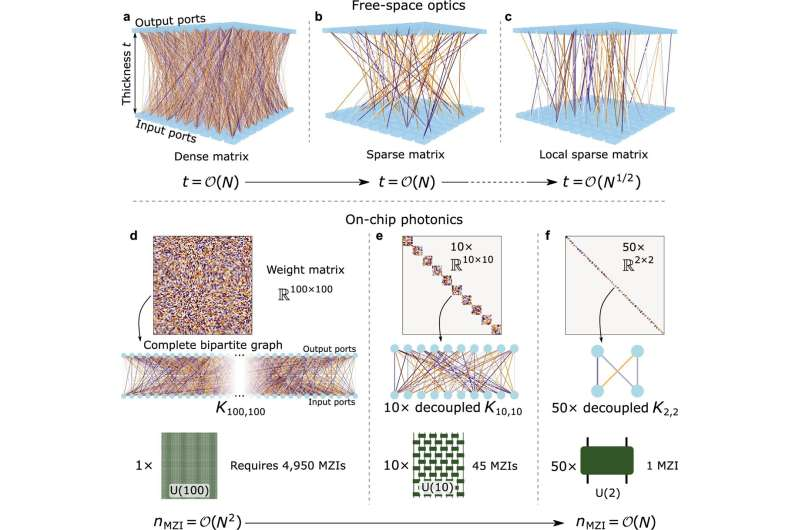

The Cornell team focused on this issue directly. Instead of asking whether optical computing is theoretically powerful or energy-efficient—which it clearly is—they asked a more grounded question: how large does an optical device need to be as the computational task becomes more complex? This led them to derive new scaling laws that apply to both free-space optical systems and photonic integrated circuits.

New Scaling Laws for Optical Systems

The researchers analyzed how the physical dimensions of optical computing devices must grow as task complexity increases. They showed that there are fundamental lower bounds on the size of these systems, imposed by the physics of wave propagation and interference. These limits apply regardless of how clever the device design is.

However, the study also revealed something encouraging: many existing optical systems are far from optimal in how they use space. In other words, optical computers can often be made much smaller without sacrificing much performance, if they are designed intelligently.

This insight led the researchers to explore new design strategies inspired by modern machine learning.

Borrowing an Idea from Deep Learning: Pruning

One of the most interesting aspects of the study is how it adapts a concept from artificial intelligence called neural pruning. In deep learning, pruning involves removing redundant or low-impact parameters from a neural network, reducing its size and complexity while maintaining nearly the same performance.

The Cornell researchers applied this idea to optical systems. They carefully analyzed the connectivity patterns within optical computing devices—specifically, how different light waves overlap and interact throughout the system. Excessive overlap often contributes little to accuracy but consumes valuable space.

By developing optics-specific pruning techniques grounded in wave physics, the team was able to penalize unnecessary light-wave interactions. This dramatically simplified the optical networks while keeping performance nearly intact.

The result was striking: optical computing systems performing the same task could be reduced to just 1% to 10% of the size of their conventional designs.

What This Means for Large AI Models

To put their findings into perspective, the researchers estimated how large an optical system would need to be to handle the linear operations used in large language models, such as those underlying tools like ChatGPT. These models often involve anywhere from 100 billion to 2 trillion parameters, which sounds impossibly large at first glance.

According to the study, a free-space optical setup could theoretically handle computations at this scale in a device roughly 1 centimeter thick. This is not a claim that a complete optical version of a large language model exists today, but rather a demonstration that space alone is not the limiting factor many assumed it to be.

To approach this theoretical limit, the researchers point to emerging optical components such as ultra-thin metasurfaces and spaceplates, which can manipulate light in extremely compact forms. These technologies were also discussed in the team’s earlier work and are rapidly advancing.

Diminishing Returns and Smart Trade-Offs

Another important finding from the study is the presence of diminishing returns when increasing the size of optical devices. Beyond a certain point, making an optical system larger does not significantly improve inference accuracy. For some applications, it is actually better to accept a small performance loss in exchange for a much smaller and more efficient device.

This insight is particularly valuable for real-world deployment, where space, cost, and energy consumption all matter. It suggests that optimal optical computing designs are not necessarily the largest or most complex ones, but those that strike a careful balance between size and performance.

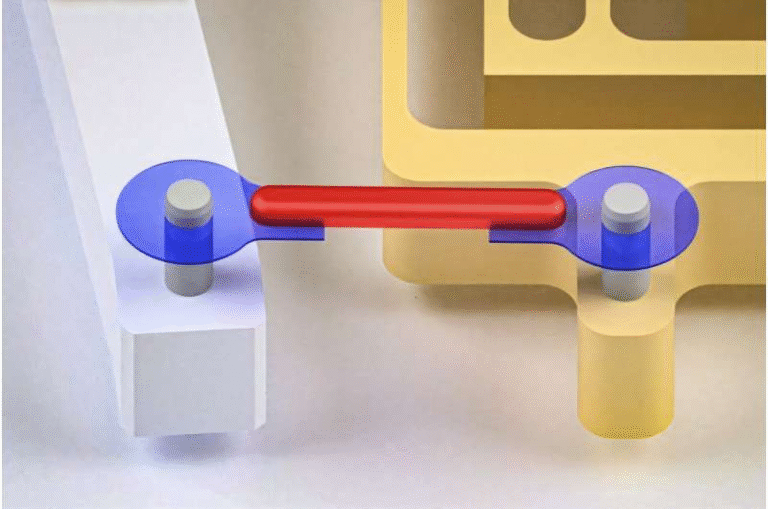

Free-Space Optics vs Photonic Circuits

The study examines both free-space optical systems, where light propagates through open space, and photonic integrated circuits, where light travels through waveguides on a chip. Each approach has different scaling behaviors and design constraints.

Free-space systems offer flexibility and can, in principle, handle very large computations in relatively thin devices. Photonic circuits, meanwhile, offer better integration with existing semiconductor technologies but face stricter constraints on routing and confinement.

The new scaling laws apply to both platforms and provide a unified framework for understanding how space-efficient optical computing can be achieved.

Why Fully Optical Computers Are Still a Long-Term Goal

Despite these advances, the researchers are careful not to oversell the idea of fully optical computers replacing GPUs anytime soon. There are limitations beyond size, including challenges with nonlinear operations, programmability, and general-purpose control.

Instead, the most promising near-term applications lie in hybrid optical-electronic systems. In these systems, light is used for what it does best: fast, energy-efficient linear operations. Electronics then handle nonlinear functions, decision-making, branching logic, and overall system control.

This hybrid approach could be especially useful in imaging systems, edge computing, and other resource-limited environments where energy efficiency is critical.

Why This Research Matters

What makes this work especially important is that it brings the language of computational complexity into the physical world of hardware design. By defining and quantifying spatial complexity, the researchers provide clear design rules rather than vague promises.

The study shows that optical computing is not doomed by impractical size requirements, as some critics have feared. With careful design and physics-informed optimization, space is not necessarily the bottleneck.

As optical components continue to improve and hybrid systems become more common, these scaling laws could play a key role in shaping the next generation of AI accelerators and specialized computing hardware.

Research Paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-63453-8