MIT Researchers Identify the Key Traits That Make a Material a Strong Proton Conductor

A wide range of modern and emerging energy technologies depend on one tiny particle doing a big job: the proton. From hydrogen fuel cells and electrolyzers to experimental proton batteries and even brain-inspired computing devices, protons are increasingly being explored as an efficient alternative to heavier charge carriers like lithium ions. But one major challenge has held back their broader adoption — finding materials that can move protons quickly and efficiently, especially at lower temperatures.

Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have taken an important step toward solving that problem. In a new study published in the journal Matter, the team developed a physical model that reveals exactly which material traits matter most for proton conduction in metal oxides. Along the way, they introduced a new quantitative metric that highlights a previously underappreciated factor: the flexibility of oxygen atoms inside the material’s crystal lattice.

This work provides a clearer roadmap for designing next-generation proton-conducting materials and could accelerate progress across clean energy and low-power electronics.

Why Proton Conductors Matter So Much

Protons are the positively charged form of hydrogen, and unlike lithium or sodium ions, they have no electrons of their own. This makes them exceptionally light and potentially very fast charge carriers. Because of this, proton-based systems could enable energy technologies that are smaller, lighter, cheaper, and more abundant than current lithium-ion-based solutions.

Proton conductors already play a role in:

- Electrolyzers, which split water to produce hydrogen fuel

- Fuel cells, which generate electricity from hydrogen

- Experimental proton batteries, often water-based and made from inexpensive materials

- Neuromorphic or brain-inspired computing, where protons can mimic how biological synapses work at very low power

Despite this promise, efficient proton transport remains difficult to achieve under practical operating conditions, especially near room temperature.

The Challenge With Metal Oxides

One of the most promising classes of inorganic proton conductors is metal oxides. These materials can conduct protons effectively at high temperatures, often above 400 degrees Celsius. However, for most real-world applications — particularly electronics and portable energy devices — lower-temperature operation is essential.

Scientists have long known that certain structural and chemical features influence proton mobility, but predicting which materials will perform well has been difficult. Many design rules were qualitative or worked only for narrow families of compounds.

The MIT team set out to change that by building a model that could quantitatively predict proton mobility across a wide range of metal oxides.

How Protons Actually Move Through Oxides

Understanding proton conduction starts with understanding how protons behave inside a solid material.

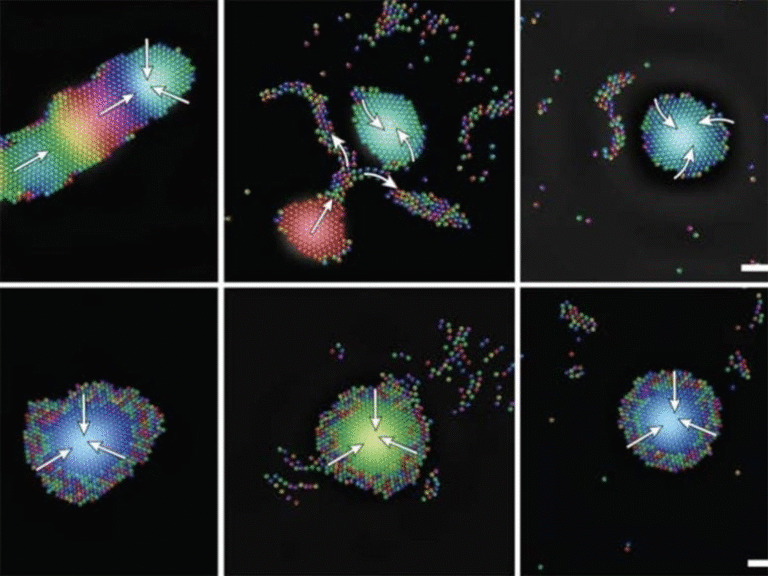

In metal oxides, protons do not move freely like electrons in a wire. Instead, they embed themselves into the electron clouds of oxygen ions, forming a covalent O–H bond. From there, the proton can hop to a neighboring oxygen ion through a hydrogen bond.

This process involves several steps:

- The proton bonds to an oxygen atom

- It hops to a nearby oxygen via a hydrogen bond

- The O–H bond rotates after each hop, preventing the proton from simply bouncing back

This sequence of hopping and rotation is energy-dependent, meaning that the material’s structure plays a critical role in how easily protons can move.

A New Metric That Changes the Picture

The breakthrough in this study came from recognizing that oxygen atom flexibility matters just as much as static structure.

The researchers introduced a new metric called O…O fluctuation, which measures how much the distance between neighboring oxygen ions changes due to thermal vibrations, known as phonons, at finite temperatures. In simple terms, this metric captures how flexible or “soft” the oxygen sublattice is inside a material.

By analyzing many metal oxides, the team discovered that greater oxygen sublattice flexibility significantly lowers the energy barrier for proton hopping. Flexible oxygen networks make it easier for protons to transfer from one site to another.

This was the first time such flexibility had been quantified and shown to be a major predictor of proton mobility across different oxide materials.

Ranking the Most Important Material Traits

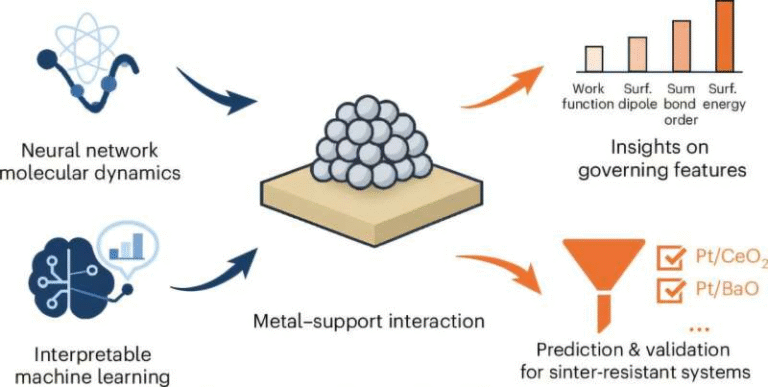

To build their predictive model, the MIT researchers examined seven different material features, including structural, chemical, electronic, and dynamic properties. They then ranked these features based on how strongly they influenced proton transfer barriers.

Two traits clearly stood out:

- Hydrogen bond length: Shorter hydrogen bonds between oxygen atoms make proton transfer easier and faster. This finding aligns with previous studies but is now supported by broader quantitative evidence.

- Oxygen sublattice flexibility (O…O fluctuation): More flexible oxygen frameworks enable smoother proton motion and lower energy barriers.

These two features turned out to be the most powerful predictors of proton conductivity, outperforming several traditional descriptors commonly used in materials science.

Why This Model Is So Useful

The researchers believe their findings apply to a broad range of inorganic proton conductors, not just the specific compounds studied. Because the model links proton mobility to fundamental physical traits, it can be used in several powerful ways.

One immediate application is screening large materials databases. Major research groups and technology companies have already generated massive libraries of known and hypothetical materials. The MIT model can rapidly identify which of those materials are likely to conduct protons well, saving years of trial-and-error experimentation.

Another exciting possibility is the use of generative artificial intelligence. Instead of searching for existing materials, AI models could be trained to design entirely new compounds that optimize hydrogen bond length and oxygen lattice flexibility from the start.

Broader Implications for Energy and Computing

Improved proton conductors could lead to:

- More efficient fuel cells and electrolyzers operating at lower temperatures

- Affordable, water-based proton batteries as alternatives to lithium-ion systems

- Ultra-low-power computing devices that mimic biological neural networks

In all these cases, better materials could dramatically improve efficiency, durability, and scalability.

Looking Ahead

While the results are promising, the researchers emphasize caution when generalizing across all materials. Future work will focus on identifying specific composition and structural rules that naturally lead to flexible, well-connected oxygen sublattices.

Understanding how to intentionally design that flexibility — rather than discovering it by chance — is the next major challenge.

Still, this study marks an important step forward. By clearly identifying what makes a good proton conductor, MIT researchers have given scientists and engineers a much sharper set of tools for building the clean energy and computing technologies of the future.

Research paper:

https://www.cell.com/matter/fulltext/S2590-2385(25)00611-3