New Process Densifies Electrolytes and Stabilizes Lithium Anodes for Long-Lasting All-Solid-State Batteries

All-solid-state batteries have long been described as the next big leap in energy storage, promising higher energy density, faster charging, and improved safety compared to today’s lithium-ion batteries. Now, researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) in Switzerland have taken an important step toward making that promise more obvious by developing a new manufacturing process that tackles two of the most stubborn problems holding this technology back.

At the heart of this research is a clever combination of electrolyte densification and lithium anode stabilization, resulting in all-solid-state batteries that can cycle for an impressively long time without major performance loss. The work was carried out by a team led by Mario El Kazzi, head of PSI’s Battery Materials and Diagnostics group, and published in the journal Advanced Science.

Why All-Solid-State Batteries Matter

Conventional lithium-ion batteries rely on liquid electrolytes, which are flammable and limit how much energy can safely be stored. All-solid-state batteries replace this liquid with a solid electrolyte, immediately improving safety and opening the door to using lithium metal anodes instead of graphite.

Lithium metal is attractive because it can store significantly more energy than graphite, potentially leading to lighter batteries with longer range—especially important for electric vehicles, portable electronics, and stationary energy storage systems. However, lithium metal brings serious challenges that researchers worldwide have been trying to solve for years.

The Two Big Problems Holding Batteries Back

The PSI team focused on two major obstacles that have prevented all-solid-state batteries from reaching the market.

The first issue is the formation of lithium dendrites. These are tiny, needle-like metal structures that can grow from the lithium anode during charging. Over time, dendrites can penetrate the solid electrolyte, reach the cathode, and cause internal short circuits. This not only degrades performance but can also destroy the battery.

The second issue is interfacial instability between the lithium metal anode and the solid electrolyte. When lithium comes into contact with certain solid electrolytes, chemical reactions can occur that form inactive layers, consume lithium, and reduce long-term performance. This instability becomes especially problematic at high current densities, such as during fast charging.

The Solid Electrolyte at the Center of the Study

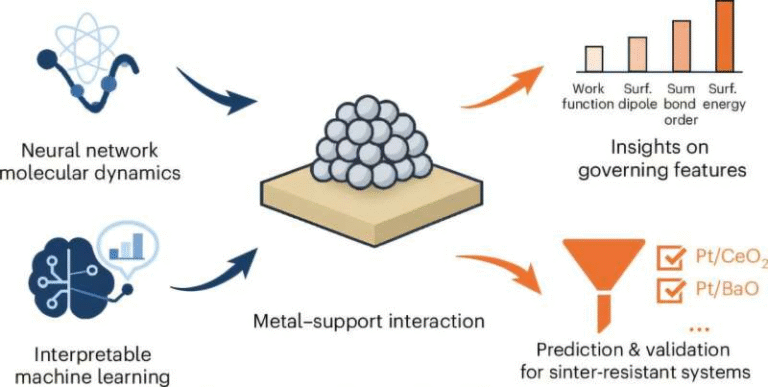

PSI researchers worked with an argyrodite-type solid electrolyte known as Li₆PS₅Cl, often abbreviated as LPSCl. This sulfide-based material is made from lithium, phosphorus, sulfur, and chlorine, and it is known for its exceptionally high lithium-ion conductivity.

High ionic conductivity is essential for fast charging and high power output. However, argyrodite electrolytes come with a drawback: they are difficult to densify. If the material contains pores or voids, lithium dendrites can exploit these weak points and grow through the electrolyte.

Why Traditional Densification Methods Fall Short

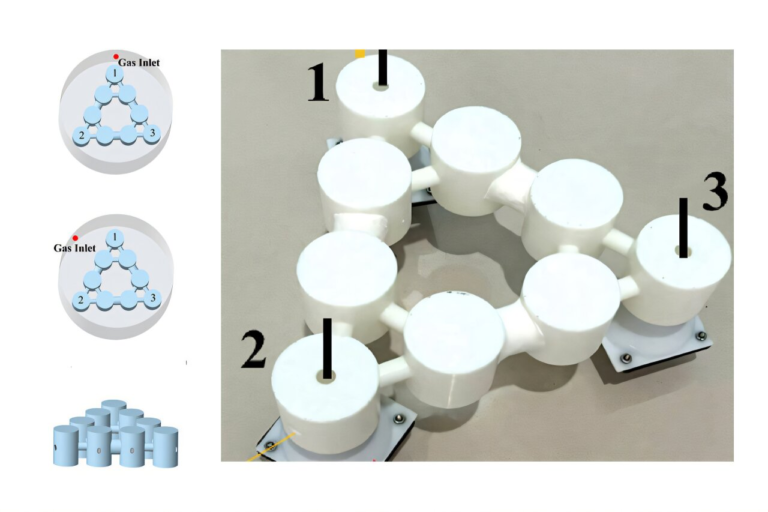

Before this study, researchers typically relied on one of two approaches to densify solid electrolytes.

One method involves applying very high pressure at room temperature, which often leads to incomplete densification and a porous microstructure. The other approach uses classical sintering, combining pressure with temperatures above 400 degrees Celsius to explain why particles fuse together.

Both approaches have downsides. Room-temperature compression tends to leave too many voids, while high-temperature sintering risks decomposing the electrolyte or causing unwanted chemical changes. The PSI team needed a solution that balanced densification with chemical stability.

A Gentler Temperature Trick That Makes the Difference

Instead of relying on extreme conditions, the researchers developed a mild sintering process. They compressed the argyrodite electrolyte under moderate pressure while heating it to only about 80 degrees Celsius.

This surprisingly gentle approach turned out to be highly effective. The particles within the electrolyte bonded closely, closing small cavities and forming a dense, homogeneous microstructure without damaging the material. The result was an electrolyte that is both mechanically robust and well-suited for rapid lithium-ion transport.

On its own, this densification already made the electrolyte far more resistant to dendrite penetration. But the team didn’t stop there.

Stabilizing the Lithium Anode With an Ultra-Thin Coating

To address interfacial instability, the researchers added a second key modification: a 65-nanometer-thick coating of lithium fluoride (LiF) applied directly to the lithium metal anode.

This ultra-thin layer was deposited under vacuum and serves as a passivation layer between the lithium and the solid electrolyte. Despite its tiny thickness, the LiF layer plays two critical roles.

First, it prevents electrochemical decomposition of the solid electrolyte when it contacts lithium, reducing the formation of inactive or “dead” lithium. Second, it acts as a physical barrier that blocks lithium dendrites from penetrating into the electrolyte.

Together, the densified electrolyte and LiF coating create a stable and durable interface capable of handling demanding operating conditions.

Impressive Performance in Long-Term Testing

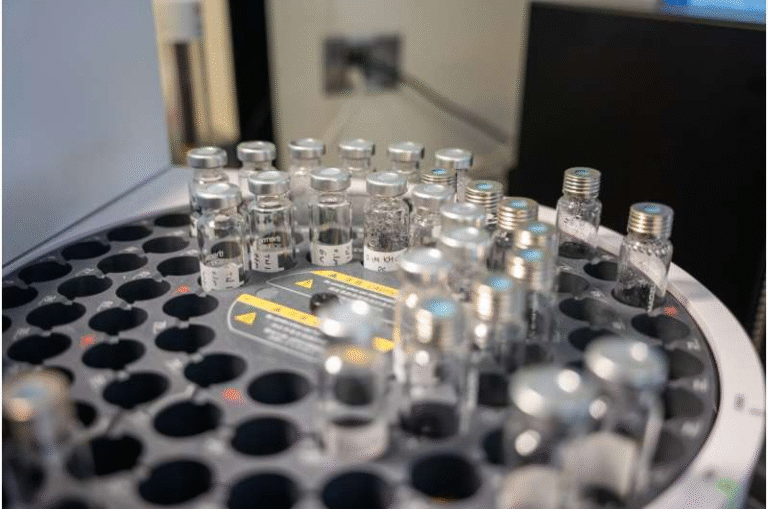

The PSI team tested their design using laboratory button cells, and the results were striking. Even under high voltage and repeated cycling, the batteries showed exceptional stability.

After 1,500 charge-discharge cycles, the cells retained around 75 percent of their original capacity. This means that the majority of lithium ions were still actively shuttling between the electrodes after extensive use.

According to the researchers, these figures are among the best reported so far for argyrodite-based all-solid-state batteries. The cells also demonstrated improved performance at higher current densities, which is essential for practical fast-charging applications.

Why This Approach Matters for Industry

Beyond performance, this work stands out for its practical implications. The mild sintering process uses low temperatures, which significantly reduces energy consumption during manufacturing. Lower energy use translates directly into lower production costs and a smaller environmental footprint.

From an industrial perspective, this makes the process far more attractive than high-temperature sintering routes. With further optimization, the researchers believe the method could be adapted for large-scale production of argyrodite-based all-solid-state batteries.

A Bit More Context on Argyrodite Electrolytes

Argyrodite materials have been widely studied in recent years because they offer an appealing balance of ionic conductivity, processability, and chemical flexibility. By adjusting their composition, researchers can tune properties such as conductivity and stability.

However, argyrodites are also known for being chemically reactive with lithium metal, which makes interface engineering essential. The PSI study clearly shows that combining microstructural control with interface passivation can unlock much better performance from these materials.

What This Means for the Future of Batteries

This research demonstrates that long-standing problems in all-solid-state batteries do not require a single magic fix. Instead, carefully combining complementary solutions—in this case, mild electrolyte sintering and lithium surface passivation—can deliver dramatic improvements.

While more work is needed before these batteries appear in commercial products, the results strongly suggest that all-solid-state batteries could soon outperform conventional lithium-ion batteries in both energy density and lifespan.

With safer operation, longer cycle life, and more efficient manufacturing, the future of solid-state energy storage looks increasingly realistic.

Research paper:

https://advanced.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/advs.202521791