New Research Shows AI Reasoning Models Pay a Human-Like Cost for Thinking Through Hard Problems

Large language models like ChatGPT have become famous for producing fluent text almost instantly. Ask them to draft an email, summarize a document, or plan a meal, and the response appears in seconds. For a long time, however, these systems struggled with tasks that require multi-step reasoning, such as complex math problems or abstract logic puzzles. That situation has changed rapidly over the past couple of years, and new research now suggests something even more surprising: the way advanced AI models “spend effort” on hard problems closely mirrors how human brains allocate thinking effort.

A recent study from researchers at MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), explores what the scientists call the “cost of thinking.” Their central finding is simple but striking: problems that take humans longer to solve also demand more internal computation from modern reasoning-focused AI models. In other words, the mental effort required by people and the computational effort required by these AI systems increase in similar ways as problems become more difficult.

This convergence was not something AI developers were intentionally aiming for. Yet the results suggest that, at least in one measurable dimension, advanced reasoning models are behaving in a way that resembles human cognition.

What Are Reasoning Models and How Are They Different?

Traditional large language models are primarily trained to predict the next word or token in a sequence based on patterns in massive text datasets. This makes them extremely good at language-related tasks but historically weaker at structured reasoning. They often failed at math, logic, or problems that required holding multiple steps in mind.

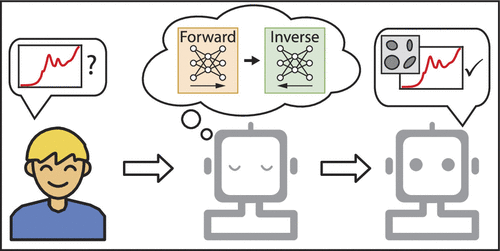

Reasoning models are a newer generation of AI systems designed to overcome these limitations. They are still neural networks, but their training encourages them to break problems into steps, explore possible solutions, and internally evaluate whether their reasoning is correct before producing an answer.

One of the key changes that enabled this improvement is the use of reinforcement learning during training. Instead of simply predicting likely text, these models are rewarded for arriving at correct solutions and penalized for mistakes. Over time, this pushes the model to explore problem-solving strategies that work reliably, even if they require more internal computation.

The result is that reasoning models often take longer to respond than earlier systems. However, this extra time is usually worth it, because they can solve problems that older models consistently got wrong.

Measuring the “Cost of Thinking” in Humans and Machines

To compare humans and AI fairly, the researchers needed a way to measure thinking effort in both groups.

For human participants, the metric was straightforward: response time. The researchers measured how long it took people to solve each problem, down to the millisecond. Longer times were interpreted as higher cognitive effort.

For AI models, raw processing time was not useful because it depends heavily on hardware and system configuration. Instead, the researchers measured the number of internal tokens generated during reasoning. These tokens are part of the model’s internal chain of thought, not something users normally see. They act as a rough proxy for how much internal computation the model performs while solving a problem.

You can think of this as the AI version of thinking silently to oneself.

The Tasks Used in the Study

Both humans and reasoning models were given the same set of tasks across seven different problem categories. These included:

- Numeric arithmetic, such as basic calculations

- Intuitive reasoning problems

- More abstract tasks that require pattern recognition and rule inference

One of the most demanding categories was the ARC (Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus) challenge. In these problems, participants see pairs of colored grids that illustrate a transformation rule. They must infer that rule and then apply it to a new grid. These tasks are widely considered difficult because they require abstraction rather than memorization.

Across all categories, a clear pattern emerged. Problems that humans solved quickly required fewer tokens from the AI models. Problems that humans struggled with took longer and caused the models to generate many more internal tokens.

The alignment was not limited to individual problems. Entire classes of problems that were costly for humans were also costly for the models. Arithmetic tasks were among the least demanding, while ARC-style tasks were the most demanding for both groups.

Why This Parallel Is So Surprising

The researchers emphasize that no one designed these models to think like humans. Engineers care primarily about performance and accuracy, not biological plausibility. The fact that a similarity emerged anyway is what makes the finding so interesting.

It suggests that when systems are optimized to solve complex reasoning problems efficiently, they may naturally converge on strategies that resemble human approaches, at least in terms of how effort scales with difficulty.

That said, the researchers are careful not to overstate the result. The models are not replicating human intelligence, consciousness, or brain activity. The similarity exists at a specific level: the relationship between problem difficulty and computational effort.

Do These Models Actually Think in Language?

One important clarification from the study concerns the internal reasoning tokens themselves. Although these tokens often look like language, the researchers argue that the real computation likely happens in an abstract, non-linguistic space.

The internal chains of thought can contain errors or seemingly nonsensical steps, even when the final answer is correct. This suggests that language-like tokens are not the true medium of reasoning but rather a surface-level representation of deeper internal processes.

This mirrors human cognition in an interesting way. People often do not consciously verbalize every step of their reasoning, especially for complex or intuitive tasks. Much of human thought happens below the level of explicit language.

Open Questions and Future Directions

While the study reveals a compelling parallel, it also raises new questions. The researchers want to know whether reasoning models use representations of information that are in any way comparable to those used by the human brain. They are also interested in how these representations are transformed into solutions.

Another open question is how well reasoning models can handle problems that require real-world knowledge not explicitly present in their training data. Humans rely heavily on shared background knowledge and lived experience, and it remains unclear how closely AI systems can approximate this ability.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding the cost of thinking in AI is not just an academic exercise. It has practical implications for:

- Designing more efficient and reliable reasoning systems

- Predicting when models are likely to fail or require more computation

- Using AI as a tool to better understand human cognition itself

If reasoning models reliably track human difficulty across tasks, they could even become useful tools for studying which problems are genuinely hard for people and why.

The Bigger Picture

This research fits into a broader trend in artificial intelligence: as models become more capable, they are starting to exhibit behaviors that echo aspects of human cognition, even without being explicitly programmed to do so. The similarities do not mean machines think like humans in a literal sense, but they do suggest that certain constraints and solutions may be universal when tackling complex reasoning problems.

The idea that both humans and machines pay a comparable price for thinking offers a new lens through which to understand intelligence, whether biological or artificial.

Research Paper:

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2520077122