Programmable Acoustic Metamaterial Can Morph Into More Configurations Than There Are Atoms in the Universe

Researchers at the University of Connecticut have developed a programmable acoustic metamaterial that pushes the limits of what engineered materials can do. This new material can be reconfigured in real time into more possible physical states than the number of atoms in the observable universe, a claim that sounds almost unreal but is firmly grounded in mathematics, engineering, and experimental validation. The work comes from the Wave Engineering for eXtreme and Intelligent maTErials (We-Xite) lab, led by engineering assistant professor Osama R. Bilal, and is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

At its core, this research is about control—specifically, precise, adaptable control of sound waves. Unlike traditional materials, which have fixed properties once manufactured, this metamaterial can be reshaped and retuned electronically, allowing it to bend, focus, dampen, or redirect sound in ways that were previously impossible.

What Makes This Metamaterial Different

Metamaterials are artificially engineered materials designed to achieve properties not commonly found in nature. In acoustics, this usually means materials that can manipulate sound waves in unconventional ways, such as steering them around objects, trapping them, or amplifying their effects. Historically, however, most acoustic metamaterials have had a major limitation: they are static. Once fabricated, their shape and function are locked in.

The UConn team set out to break this limitation. Their solution is a reconfigurable platform that can be programmed repeatedly without rebuilding the material. This makes it far more versatile than conventional designs, especially for applications where sound conditions or requirements change over time.

The Physical Design of the Material

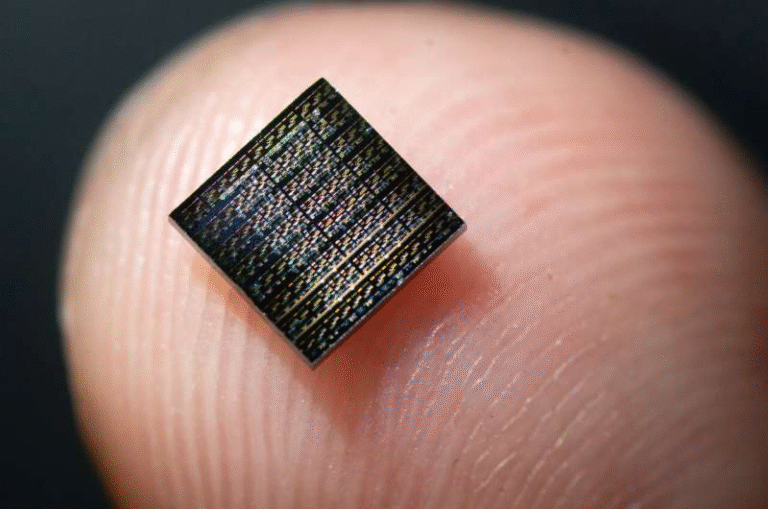

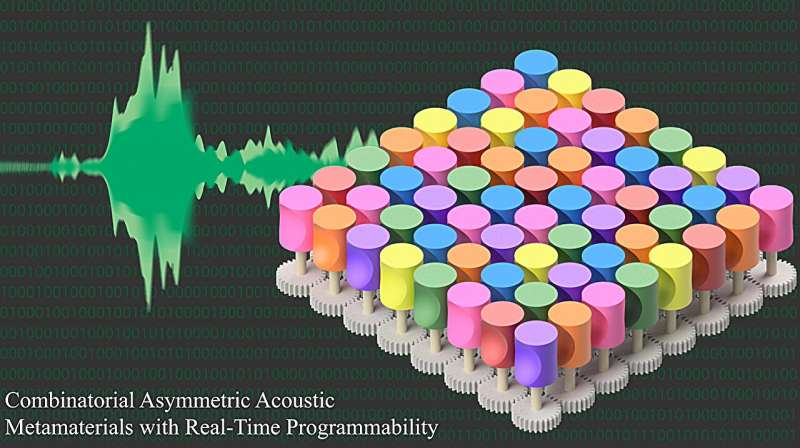

The metamaterial consists of 121 individual units arranged in an 11×11 grid. Each unit is a vertical pillar with an asymmetric shape, featuring one or more concave faces. The researchers often describe the shape as resembling an apple core, a design choice that plays a crucial role in how sound waves interact with each pillar.

Every pillar is connected to a small motor that allows it to rotate independently. These motors are highly precise, enabling rotation in one-degree increments. Because each pillar can be oriented differently, the overall structure can take on an enormous number of unique configurations.

When sound waves pass through the grid, they scatter, reflect, and interfere with one another depending on how the concave surfaces are oriented. Changing the orientation of even a few pillars can completely alter the path the sound waves take through the material.

Why the Number of Configurations Is So Extreme

The claim that this metamaterial has more configurations than atoms in the universe comes from combinatorial mathematics. With 121 pillars, each capable of rotating through hundreds of discrete angular positions, the number of possible arrangements grows exponentially. When combinations of pillars are considered together, the total number of configurations becomes astronomically large.

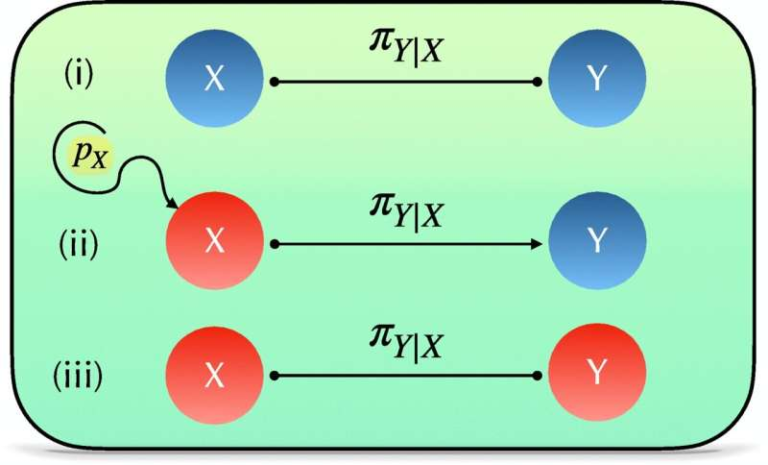

The researchers also introduce the idea of “supercells.” Instead of treating each pillar individually, groups of two, four, or more pillars can be programmed to work together as a single functional unit. This approach expands the design space even further, allowing engineers to fine-tune how sound behaves across the entire structure.

This combinatorial flexibility is what sets the platform apart and makes it such a significant advance for the field of metamaterials.

How the Material Manipulates Sound

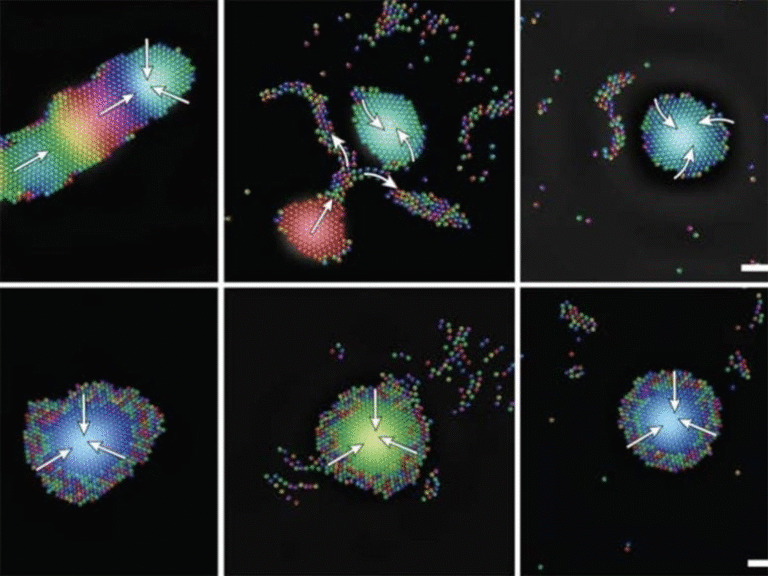

By carefully choosing pillar orientations, the metamaterial can perform a wide range of acoustic functions. These include focusing sound waves to a single point, dispersing them to reduce intensity, or guiding them along specific paths. Because the system is programmable, these behaviors can be changed in real time without physically altering the material.

One particularly striking demonstration involves acoustic focusing. Low-amplitude sound waves can be guided to converge at a precise location and then disperse afterward. This capability is especially valuable in medical and scientific applications where delicate, localized control is required.

The platform can also mimic behaviors seen in advanced physics concepts such as topological insulators. In this case, sound waves are forced to travel along the edges of the material while avoiding the interior, even in the presence of imperfections or obstacles.

Potential Medical and Technological Applications

The ability to control sound with such precision opens the door to numerous practical uses. In medicine, the material could improve ultrasound imaging, non-invasive therapies, and acoustic tweezers, which use sound waves to manipulate tiny particles or cells.

For conditions like brain tumors or kidney stones, focused sound could be used to weaken or target specific areas without damaging surrounding tissue. Because the metamaterial works effectively with low-intensity sound, it offers a safer and more controlled alternative to high-energy acoustic methods.

Beyond healthcare, the technology could influence soundproofing systems, adaptive architectural acoustics, and even drag reduction in moving objects. In separate research efforts, similar metamaterial concepts are being explored to reduce resistance on surfaces, potentially lowering fuel consumption in transportation.

A Platform for Fundamental Physics Research

This metamaterial is not just a practical tool; it is also a powerful experimental platform for studying wave physics. Concepts that are difficult to observe directly—such as wave localization, boundary-guided propagation, and symmetry-breaking effects—can be explored using sound instead of electrons or photons.

Because the material is programmable, researchers can rapidly test hypotheses by changing configurations electronically rather than fabricating new samples. This dramatically speeds up experimental cycles and lowers costs.

The Challenge of Too Many Possibilities

The sheer size of the design space introduces a new challenge: no human can manually analyze every configuration. With so many possible states, calculating how sound will behave in each one would take longer than a human lifetime—likely many lifetimes.

To address this, the research team is turning to artificial intelligence and machine learning. By training algorithms to recognize patterns and predict outcomes, the material could eventually become self-optimizing, automatically adjusting its configuration to achieve a desired acoustic effect.

This vision aligns with the lab’s long-term goal of creating intelligent materials that combine physical adaptability with computational decision-making.

Years of Development and Collaboration

The project is the result of years of work and close collaboration between faculty and students. Melanie R. Keogh, the first author of the study, began working with Bilal as an undergraduate after taking his vibrations course. Her expertise in electronics proved essential, as the system required precise control of every motor in the grid.

Building the circuitry, stacking the pillars accurately, and ensuring reliable real-time control was a massive engineering task. The success of the project highlights the role of hands-on research training in advancing cutting-edge science.

Why This Research Matters

This programmable metamaterial represents a major shift in how materials are designed and used. Instead of building a new material for every function, engineers can now rely on a single platform that adapts on demand. This flexibility has implications far beyond acoustics, pointing toward a future where materials are not just passive structures, but active, intelligent systems.

As research continues, this platform may serve as a foundation for new technologies that blend physics, engineering, and artificial intelligence in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Research paper: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2502036122