Reservoir Thermal Energy Storage Could Transform How Data Centers Handle Cooling and Energy Costs

The rapid growth of artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and large-scale data processing is pushing global data center electricity consumption steadily upward. While the servers themselves consume the most power, cooling systems are the second-largest energy drain, and they become especially demanding during hot summer months. A recent study published in Applied Energy highlights a promising solution to this challenge: reservoir thermal energy storage, or RTES.

Researchers from the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR)—formerly known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)—have conducted a detailed techno-economic analysis showing that RTES can dramatically reduce electricity use, operating costs, and strain on the power grid, all while providing reliable, continuous cooling for data centers.

Why Data Center Cooling Has Become a Critical Problem

Modern data centers operate 24/7 and must maintain precise temperature ranges to keep servers functioning safely. As computing demand grows, cooling loads increase alongside it. Traditional cooling systems rely heavily on vapor-compression chillers, which use energy-intensive refrigeration cycles. These systems are generally efficient under mild conditions, but their performance drops sharply during hot weather, precisely when cooling demand is highest and electricity prices tend to peak.

This creates a compounding problem: higher cooling demand leads to higher electricity use, which in turn increases costs and places additional stress on regional power grids. The NLR team set out to explore whether a fundamentally different approach—one that shifts cooling energy use away from peak hours—could offer a better alternative.

What Is Reservoir Thermal Energy Storage (RTES)?

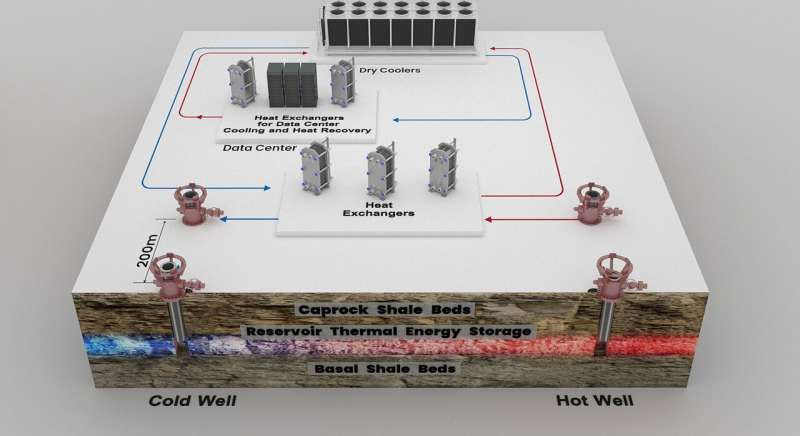

RTES is a form of underground thermal energy storage that takes advantage of naturally occurring subsurface reservoirs to store cold energy for later use. Instead of producing cooling on demand during the hottest parts of the year, RTES allows data centers to store cold when it is cheap and plentiful, then use it when it is most needed.

The system works on a seasonal cycle:

- During cold periods, such as winter or nighttime hours, outdoor air and low-cost electricity are used to chill water.

- This chilled water is injected into underground reservoirs through dedicated wells.

- During hot periods, especially in summer, the stored cold water is pumped back to the surface.

- The cold water passes through a heat exchanger, absorbing heat from the data center’s warm return water and providing direct cooling.

- The warmed water is then sent back underground into a separate hot well, where it remains until the next recharge cycle.

This continuous loop keeps the underground system in thermal balance and allows cooling to be delivered with minimal electricity use during peak demand periods.

Why Underground Reservoirs Are Well Suited for Thermal Storage

RTES systems typically rely on brackish or saline aquifers, which are naturally isolated by surrounding rock layers. These reservoirs are chemically stable, slow-moving, and unsuitable for drinking water, making them ideal candidates for long-term thermal energy storage.

In many locations, wells can be drilled to depths of a few hundred meters to around one kilometer, depending on local geology. Once installed, these underground reservoirs can store large amounts of thermal energy for extended periods with relatively low losses.

How the Study Was Designed

The research team modeled two RTES-based cooling scenarios and compared them to a conventional cooling system. Key aspects of the study include:

- Four wells drilled to a depth of 275 meters

- A 20-year operational lifespan

- A seasonal recharge cycle, with cold energy discharged in summer and replenished in winter

- Use of dry coolers, which provide so-called “free cooling” by using fans and heat exchangers instead of energy-intensive compressors

- One scenario that also included waste heat recovery, capturing heat from the data center to provide building heating during winter

For comparison, the control scenario relied on dry coolers paired with vapor-compression chillers, which represent a common approach in existing data centers.

Key Findings on Efficiency and Cost

The results were striking. By eliminating most of the refrigeration cycle during peak cooling periods, RTES systems achieved dramatically higher efficiency than traditional chillers.

- The coefficient of performance (COP) for RTES during peak summer conditions reached 16.5, compared to 2.4 for conventional chillers.

- This means RTES was nearly seven times more efficient when cooling demand was highest.

Cost savings were equally significant. The study evaluated the levelized cost of cooling, which spreads total system costs over its lifetime:

- Conventional cooling systems: approximately $15 per megawatt-hour

- RTES systems: approximately $5 per megawatt-hour

For data centers that operate continuously, these reductions translate into substantial long-term savings while maintaining reliable cooling performance.

Real-World Data Center Scenarios

To test RTES across different scales and climates, the researchers examined three types of facilities:

- A 5-megawatt high-performance computing data center in Colorado

- A 30-megawatt cryptocurrency mining facility in Texas

- A 70-megawatt hyperscale data center in Virginia

A broader multilab technical report evaluated all three sites, including water savings and operational impacts, while a separate paper in the Journal of Clean Energy and Energy Storage focused specifically on the Texas and Virginia facilities.

Beyond Cooling: Grid and Environmental Benefits

Although the study did not explicitly model time-of-use electricity pricing, RTES naturally shifts energy use toward off-peak periods, reducing strain on the grid during summer heat waves. This has important implications for grid stability as data center demand continues to grow.

In addition, RTES systems that rely on dry coolers do not consume water on-site, unlike traditional cooling towers. This is particularly valuable in water-stressed regions, where data center water use has become a growing concern.

How RTES Fits Into the Bigger Energy Picture

The RTES work builds on ongoing research into Cold Underground Thermal Energy Storage (Cold UTES) supported by the U.S. Department of Energy. These efforts aim to reduce peak cooling demand, lower operating costs, and expand the role of geothermal technologies beyond heating.

Researchers at NLR are now collaborating with teams from the University of Chicago, Princeton University, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to compare RTES with other water-based storage approaches, such as aquifer thermal energy storage and borehole thermal energy storage. The goal is to identify which systems are best suited to different geological and regional conditions.

Why This Research Matters

As data centers continue to expand worldwide, cooling will remain one of their most significant energy challenges. RTES offers a way to decouple cooling demand from peak electricity use, delivering high efficiency, lower costs, and reduced environmental impact. While site-specific factors like geology and climate will determine feasibility, the study clearly shows that underground thermal storage has serious potential as a next-generation cooling solution.

Research References

Techno-economic performance of reservoir thermal energy storage for data center cooling system

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.125858

Addressing Data Center Cooling Needs Through the Use of Reservoir Thermal Energy Storage Systems

https://doi.org/10.1142/S2811034X25500029