Scientists Have Found a Surprisingly Simple Way to Extract Lithium From Low-Quality Brines

Lithium sits at the heart of today’s clean energy transition. It powers electric vehicles, supports renewable energy storage, and underpins much of the modern battery economy. Yet even as demand surges worldwide, accessing lithium in a way that is both economical and environmentally responsible remains a major challenge. A new discovery from researchers at the University of Michigan could significantly change that equation, especially for lithium sources long considered impractical.

The research reveals a counterintuitive membrane-based method that can selectively extract lithium from so-called low-quality brines—salty waters that contain lithium but are dominated by magnesium. Until now, these brines were largely ignored due to technical and economic hurdles. This new approach could unlock vast untapped lithium resources and reshape how the industry thinks about brine mining.

Why Lithium Extraction Is Such a Big Deal

Lithium is currently obtained in two main ways: mining solid ore and extracting it from brines. Ore-based mining is expensive, energy-intensive, and often environmentally damaging, with risks of contaminating nearby water sources. Brine extraction, by contrast, is seen as more promising because over half of the world’s lithium reserves are believed to exist in brines.

Traditionally, lithium-rich brine is pumped into large evaporation ponds. Over months or even years, sunlight evaporates the water, leaving behind concentrated salts. Chemicals are then added to remove unwanted elements until lithium can finally be extracted. While this method works for high-quality brines, it struggles badly with brines that contain large amounts of magnesium, which behaves chemically similar to lithium.

When magnesium levels are six times higher than lithium or more, extraction becomes complicated, wasteful, and expensive. Additional chemicals are needed to remove magnesium, generating more waste and driving up costs. As a result, many lithium-rich brines around the world are dismissed as not worth developing.

The Problem With “Low-Quality” Brines

Most of today’s lithium production comes from high-quality brines beneath South American salt flats, such as Chile’s Salar de Atacama. Meanwhile, brines with lower lithium concentrations or high magnesium content are labeled low quality and left untouched.

This is a serious limitation. With lithium demand projected to outpace supply as early as 2029, relying only on traditional sources could stall progress in electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. Brines like those found in the Smackover Formation in Arkansas, which are rich in lithium but also magnesium, represent a massive but underused resource.

The University of Michigan research directly targets this problem.

A Membrane, Pure Water, and No Electricity

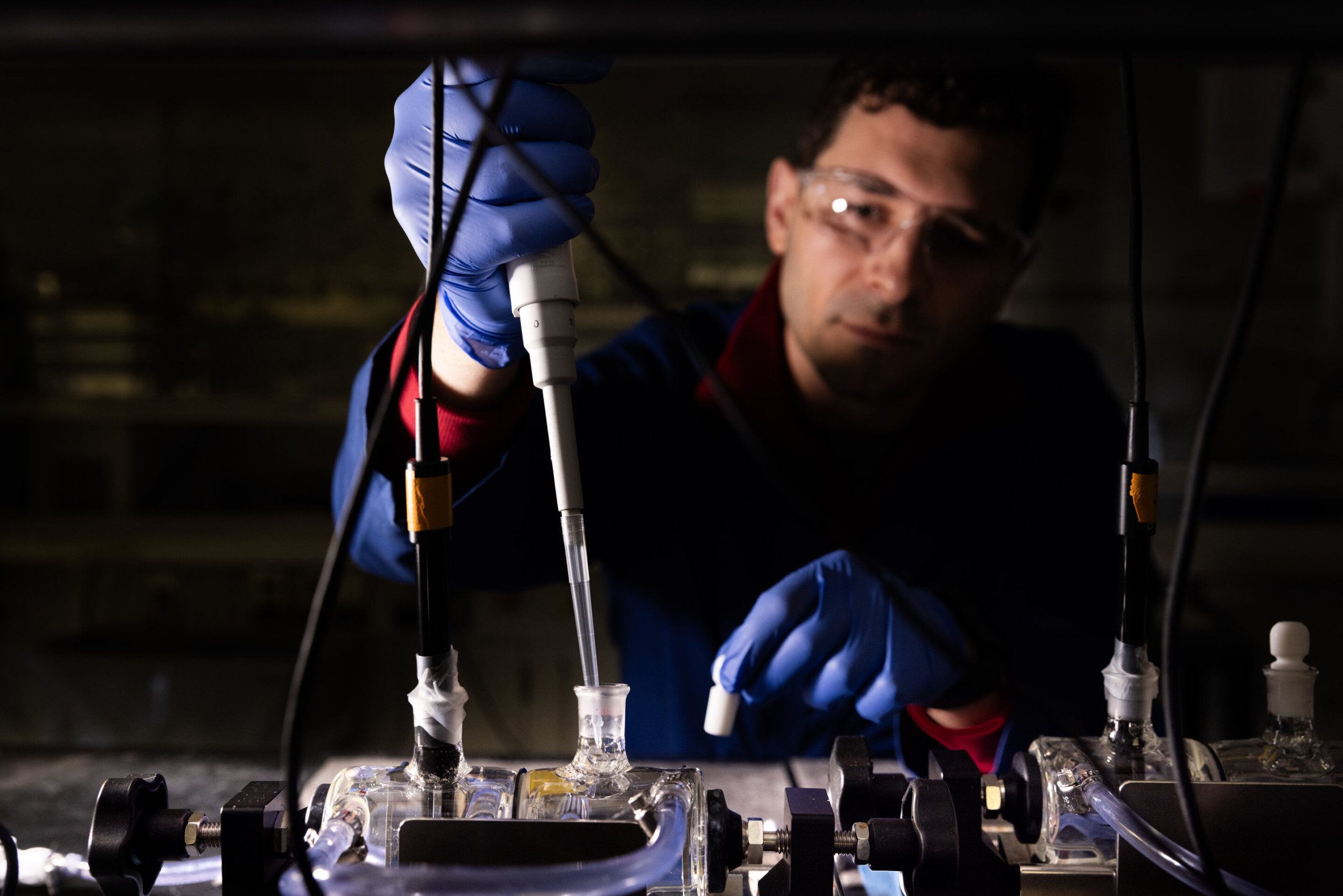

The newly discovered method is surprisingly simple. Researchers used a negatively charged membrane to separate a lithium-rich brine from pure water. Over time, lithium ions naturally diffused through the membrane into the pure water, while magnesium ions stayed behind.

What makes this so remarkable is that no external electricity, pressure, or added chemicals were required. The system works purely through diffusion and charge balance, and it performs well even at very high salinities—conditions where many other lithium separation technologies fail.

This alone sets the method apart from most existing approaches, which typically rely on energy-intensive processes such as electrodialysis or high-pressure filtration.

Why Lithium Moves First, Not Magnesium

Under normal circumstances, magnesium should win. It carries a stronger positive charge than lithium and should, in theory, be more attracted to a negatively charged membrane. That’s exactly what engineers expect when using electric currents in electrodialysis systems.

But when the researchers removed the electric current and replaced the electrolyte solution with pure water, something unexpected happened: lithium crossed the membrane first.

The explanation lies in charge balance. When a positively charged ion moves through the membrane, a negatively charged ion—chloride, in this case—must accompany it. Lithium pairs more favorably with chloride under these conditions, so when chloride diffuses into the pure water, lithium follows.

At the same time, the membrane’s own negative charge needs to be neutralized. Magnesium, with its stronger positive charge, is more strongly attracted to the membrane itself and tends to stick to it rather than pass through. Any magnesium that does slip through is quickly pulled back toward the membrane and effectively removed from the solution.

When an electric current is applied, magnesium gains enough energy to overcome this effect and cross the membrane, contaminating the lithium stream. Without electricity, lithium gets a clear advantage.

How This Differs From Conventional Lithium Separation

Most modern lithium separation techniques are energy-hungry. Electrodialysis, nanofiltration, and other membrane-based systems typically require constant electrical input and struggle with high salinity. Solar evaporation, while low-energy, consumes enormous amounts of water and land and can take years to complete.

This new diffusion-based method avoids many of those pitfalls. It uses less water, requires no electricity, and operates under conditions that match real-world brines. For communities living near lithium brine deposits, especially in arid regions, reducing water use is a major environmental and social benefit.

What the Method Can and Cannot Do

The technique excels at separating lithium from magnesium, which is one of the biggest obstacles in brine-based lithium extraction. However, it does have limitations.

The membrane cannot distinguish lithium from other ions with the same charge, such as sodium. This means the method would need to be combined with other processes—such as evaporation, lithium-selective adsorbents, or chemical precipitation—to produce battery-grade lithium.

The researchers see this as a strength rather than a weakness. By integrating multiple techniques, it may be possible to design hybrid systems that are both efficient and sustainable.

Commercial Potential and Next Steps

The research team has already applied for patent protection and is actively looking for industry partners to help bring the technology to market. Before commercialization, the next critical step is a full techno-economic analysis to determine how the method performs at scale and how it can best be integrated into existing lithium extraction workflows.

If successful, the approach could make previously unusable brines economically viable, significantly expanding the global lithium supply.

Why This Matters for the Energy Transition

Lithium demand is driven by long-term trends that show no sign of slowing. Electric vehicles, grid-scale batteries, and renewable energy systems all depend on a stable lithium supply. Without new extraction methods, shortages could delay decarbonization efforts and drive up costs.

By turning low-quality brines into viable resources, this discovery could help diversify lithium supply chains, reduce environmental damage, and lower barriers to sustainable energy technologies worldwide.

A Broader Look at Lithium Extraction Research

This work fits into a larger movement toward direct lithium extraction (DLE) technologies. Around the world, researchers are exploring advanced membranes, electrochemical reactors, and selective sorbents to replace or improve upon evaporation ponds. What makes this study stand out is its simplicity—and the fact that it emerged from what was essentially an accidental observation in the lab.

Sometimes, the biggest breakthroughs come not from complex designs, but from questioning assumptions about how materials behave under different conditions.

Research Paper:

Selective partitioning and uphill transport enable effective Li/Mg ion separation by negatively charged membranes – Nature Chemical Engineering

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-025-00312-9