Supersonic Tests Reveal That Smaller Metal Grains Can Become Weaker at Extreme Speeds

For more than 70 years, materials scientists have relied on a well-established rule when designing stronger metals: make the grains smaller. These grains are microscopic crystal regions inside a metal, and reducing their size usually increases strength. This principle, known as the Hall-Petch effect, has shaped everything from structural steel to aerospace alloys.

New research from Cornell University now shows that this trusted rule does not hold up under all conditions. When metals are deformed at ultrahigh speeds, specifically at supersonic impact rates, the relationship between grain size and strength can completely reverse. Instead of becoming stronger, metals with very small grains can actually become softer.

This finding, published in Physical Review Letters, challenges decades of conventional understanding and opens new directions for how materials might be designed for extreme environments.

The Long-Standing Rule of Metal Strength

Under normal conditions, the Hall-Petch effect works reliably. When a metal is stressed slowly or at moderate speeds, smaller grains make it harder for defects inside the metal—called dislocations—to move. These dislocations are tiny line-like defects that allow metals to permanently deform. Grain boundaries act as barriers, slowing down dislocation motion and increasing the metal’s resistance to deformation.

Because of this, engineers have long assumed that smaller grains automatically mean stronger metals, at least within a broad size range. This assumption has been validated repeatedly in laboratory tests conducted at conventional strain rates.

But those traditional tests rarely explore what happens when metals are pushed to their absolute limits.

Pushing Metals to Extreme Deformation Rates

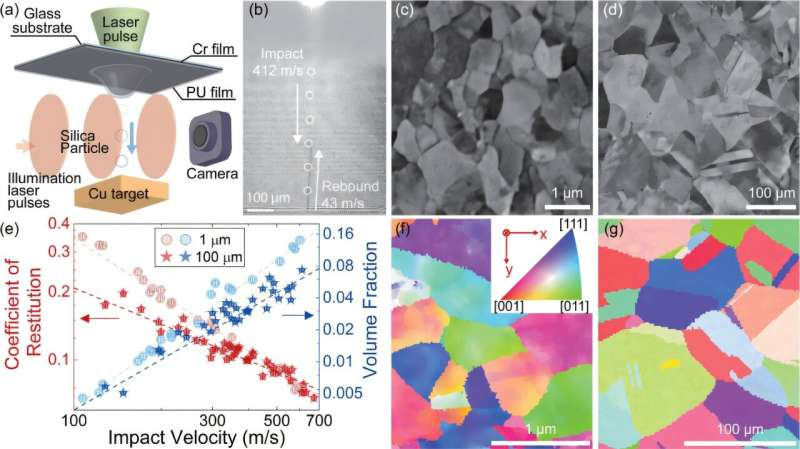

To explore how metals behave under extreme conditions, researchers at Cornell used a technique called laser-induced microprojectile impact testing, often shortened to LIPIT. This method involves firing microscopic particles at metal samples using lasers, reaching velocities that exceed the speed of sound.

These impacts produce ultrahigh strain rates, far beyond what standard mechanical tests can achieve. Until relatively recently, studying metals under such conditions was extremely difficult due to technical limitations.

Using this setup, the team tested copper samples with carefully controlled grain sizes ranging from 1 micrometer to 100 micrometers. This range sits squarely within the regime where the Hall-Petch effect is normally expected to apply.

An Unexpected Result That Refused to Go Away

The experimental results were surprising. When the copper samples were struck at supersonic speeds, the larger-grained metals consistently showed greater resistance to deformation. They produced shallower indentations and dissipated more kinetic energy during impact, both clear indicators of higher hardness.

Meanwhile, the copper samples with smaller grains, which should have been stronger according to conventional theory, performed worse under these conditions.

Because this result contradicted decades of established knowledge, the researchers initially suspected something might be wrong with the experiments. They repeated the tests, expanded the dataset, and carefully verified their measurements. Each time, the same trend appeared.

The reversal was real.

What’s Actually Happening Inside the Metal

The key to understanding this behavior lies in how dislocations move at extremely high speeds.

At ordinary strain rates, dislocations move relatively slowly, and grain boundaries effectively block them. This is where Hall-Petch strengthening dominates.

At ultrahigh strain rates, however, dislocations accelerate dramatically. When they move fast enough, they start interacting strongly with the metal’s vibrating atoms, known as phonons. This interaction creates resistance called dislocation–phonon drag.

Dislocation–phonon drag can significantly strengthen a metal under extreme deformation by limiting how fast dislocations can travel. However, this mechanism behaves differently depending on grain size.

In larger grains, dislocations have more room to accelerate and fully engage with phonons, leading to strong drag effects and higher resistance to deformation. In smaller grains, dislocation motion is more constrained, reducing the effectiveness of phonon drag. As a result, the extra strengthening expected at high strain rates is diminished or even eliminated.

This shift causes the traditional grain-size strengthening trend to reverse.

Why This Isn’t the Same as the Inverse Hall-Petch Effect

Materials scientists have known for some time that the Hall-Petch effect can break down at extremely small grain sizes, typically in the nanocrystalline regime (grain sizes on the order of tens of nanometers). In those cases, other mechanisms like grain boundary sliding become dominant.

What makes this new result especially important is that the reversal occurs in the microcrystalline range, between 1 and 100 micrometers. This is far larger than the grain sizes associated with previously known Hall-Petch breakdowns.

In other words, this is not a niche nanoscale phenomenon. It happens in grain sizes commonly used in engineering applications.

Evidence Beyond a Single Metal

Although the published study focused on copper, the researchers believe the behavior is not unique to this material. Early tests on other metals and alloys show the same general trend: at sufficiently high strain rates, the grain-size dependence of strength changes in a fundamental way.

This suggests that the effect may be universal, rooted in basic physics rather than material-specific quirks.

Why This Discovery Matters

From a scientific perspective, the findings challenge one of the most widely accepted principles in metallurgy. A rule that has guided materials design for over seven decades now has clearly defined limits.

From an engineering standpoint, the implications are just as significant.

Many real-world applications involve extreme deformation rates, including:

- Ballistic and impact-resistant armor

- Spacecraft shielding against micrometeoroids

- High-speed machining and manufacturing

- Additive manufacturing processes involving rapid solidification

- Aerospace and defense components subjected to shock loading

In these environments, simply refining grain size may no longer be the best strategy. Engineers may need to rethink how microstructures are optimized for performance under extreme conditions.

A Broader Look at Grain Size and Strength

Grain size is just one of many variables that influence a metal’s mechanical behavior. Others include alloy composition, temperature, strain rate, and defect density. What this research highlights is that strength is not a single fixed property, but a response that depends heavily on how and how fast a material is loaded.

As experimental tools continue to improve, scientists are increasingly able to explore these extreme regimes where familiar rules begin to bend—or break entirely.

Looking Ahead

The Cornell team’s work represents a step toward a more complete understanding of how materials behave across the full spectrum of deformation rates. Future studies are expected to explore additional metals, alloys, and microstructures, as well as refine theoretical models that can predict strength under extreme conditions.

Rather than replacing the Hall-Petch effect, this research adds an important layer of nuance. Smaller grains still strengthen metals under most everyday conditions—but when deformation happens at supersonic speeds, the rules change.

Understanding exactly where and why that change occurs could help engineers design safer, lighter, and more resilient materials for some of the harshest environments imaginable.

Research paper:

https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/yp9h-sr2m