Why Communication Inside Computers Always Comes With an Energy Cost

Every time you use a computer—whether you’re running complex calculations, streaming a video, or simply typing a sentence—different parts of the machine have to exchange information. The processor talks to memory, memory talks back, and signals constantly move through circuits. This internal “conversation” is so routine that we rarely think about it. But new research shows that this communication is never free. No matter how advanced or efficient a system becomes, sending information always comes with an unavoidable energy cost.

A recent study by researchers associated with the Santa Fe Institute and the University of New Mexico reveals that communication inside computational devices necessarily produces heat. This finding challenges long-standing assumptions in computer science and physics that, at least in theory, information transfer could be made energy-neutral. Instead, the work shows that there is a strict lower limit to how little energy communication can consume, and this limit applies across all communication channels—digital, physical, and even biological.

Communication Is Central to All Computation

Modern computers are built around interaction. The central processing unit (CPU) does not operate in isolation. It continuously exchanges data with memory, storage, sensors, and other components. According to Abhishek Yadav, a former Santa Fe Institute Graduate Fellow and Ph.D. researcher at the University of New Mexico, communication is not a side feature of computation—it is fundamental to it.

Despite its importance, scientists have historically focused more on the energy cost of computation itself, such as logic operations and data erasure, rather than the cost of moving information from one place to another. Over the past decade, Santa Fe Institute professor David Wolpert has led efforts to understand the thermodynamic limits of computation, including how physical laws constrain what computers can do and how efficiently they can do it.

One major gap remained: the thermodynamic cost of communication. This new research directly addresses that gap.

A Long-Standing Assumption Gets Challenged

For years, a popular theoretical idea suggested that communication could be performed without energy loss if it were done in a logically reversible way. In other words, if no information was destroyed during transmission, then no heat would need to be released.

The new study overturns that assumption.

By combining ideas from computer science, communication theory, and stochastic thermodynamics, the researchers show that communication always produces heat, even when it is logically reversible. This heat generation is not a flaw of engineering or an artifact of inefficient hardware. It is a fundamental consequence of physics.

Understanding Communication Through Thermodynamics

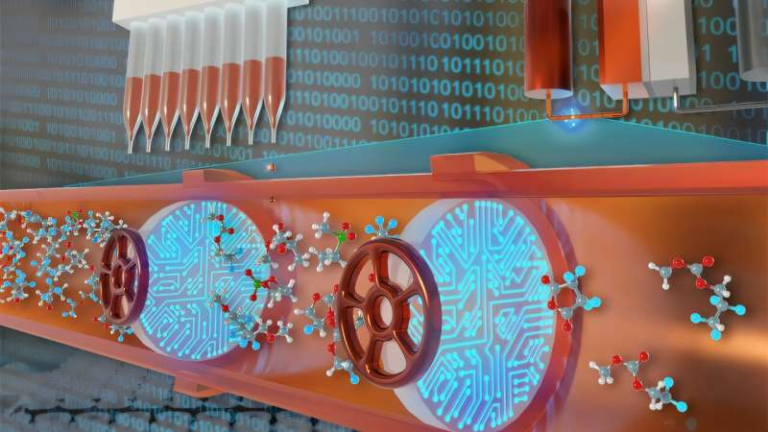

The researchers used a logical abstraction of a generic communication channel. This abstraction does not depend on the specific technology involved. It applies equally to optical fibers, electrical circuits, wireless links, and even neurons in the brain.

Real-world communication channels are always noisy. Signals degrade, interference occurs, and errors creep in. The study demonstrates that when information passes through such a noisy channel, the system must dissipate a minimum amount of heat. Crucially, this minimum heat dissipation is tied to the amount of useful information, known technically as mutual information, that successfully makes it through the noise.

In simple terms, the more meaningful information you transmit, the more heat must be generated. This result holds regardless of how advanced or optimized the system is.

Why Noise Makes Energy Costs Unavoidable

Noise plays a central role in the findings. In an ideal, perfectly noise-free world, one might imagine information moving effortlessly. But in reality, noise is unavoidable, whether it comes from thermal fluctuations, environmental interference, or internal system imperfections.

To ensure that information survives this noise, physical processes must actively maintain distinctions between different signals. That maintenance requires energy, and that energy ultimately dissipates as heat. The researchers show that this dissipation cannot be eliminated—it can only be minimized within strict bounds.

Encoding and Decoding Come With Their Own Costs

Modern communication systems rarely send raw data directly. Instead, they rely on encoding and decoding algorithms to protect information from noise. Error-correcting codes, redundancy, and signal processing techniques all help ensure accuracy.

However, the study reveals an important tradeoff: greater reliability requires greater energy expenditure. Encoding and decoding themselves have thermodynamic costs. As accuracy increases, so does heat dissipation.

This insight has major implications for technologies that prioritize reliability, such as data centers, telecommunications networks, and high-performance computing systems. Improving accuracy is not free—it comes with an energy price tag.

Implications for Computer Architecture

One area where these findings could have a major impact is computer design. Today’s computers largely rely on the von Neumann architecture, where memory and processing are separate. This separation forces constant communication between components, which now appears to be a significant source of unavoidable energy loss.

Yadav suggests that understanding these fundamental limits could inspire new computer architectures that reduce communication costs by design. Systems that integrate memory and processing more closely, or that take inspiration from biological computation, may be better positioned to operate near thermodynamic limits.

Lessons From the Human Brain

The study’s conclusions apply not only to machines but also to natural systems. The human brain is a striking example. It consumes roughly 20 percent of the body’s total energy, yet it performs extraordinarily complex computations far more efficiently than today’s computers.

Neurons constantly communicate via electrical and chemical signals, and this communication is also subject to thermodynamic costs. The fact that the brain operates so efficiently suggests that evolution has found ways to manage communication costs effectively, even if it cannot eliminate them.

Understanding how biological systems cope with these constraints could help engineers design more energy-efficient artificial systems in the future.

Why This Research Matters Beyond Computing

Communication is not limited to computers. It underpins modern society, from internet infrastructure and mobile networks to transportation systems and biological signaling. The discovery that communication has an unavoidable thermodynamic cost provides a unifying physical principle that applies across disciplines.

By establishing firm lower bounds on energy use, the research offers a clearer framework for evaluating efficiency claims and guiding future innovation. It also sets realistic expectations: no matter how advanced technology becomes, there will always be a minimum energy cost to moving information.

Looking Ahead

This work opens the door to deeper questions. How close do current systems operate to these theoretical limits? Can future technologies approach them more closely? And what can engineers learn from natural systems that have evolved under the same physical constraints?

While the study does not provide immediate engineering solutions, it lays essential groundwork. By clarifying what is fundamentally possible—and what is not—it helps chart a more informed path toward energy-efficient computation and communication.

Research paper:

Minimal thermodynamic cost of communication – Physical Review Research (2025)

https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/qvc2-32xr