Why Pragmatism Grew from U.S. Soil

Pragmatism feels American.

Not just in origin, but in tone, attitude, and even its posture toward truth. But I’ve always been curious: why did it actually grow out of U.S. soil, and not, say, Britain or France—places with similar political liberalism and growing scientific traditions?

Most of us agree that pragmatism isn’t just a philosophical system—it’s a reflection of a broader cultural mindset. What I want to do here is dig into that soil a bit more.

I’ll argue that pragmatism grew in America not just because of historical accident, but because of a very particular cultural mix—a frontier spirit, Protestant epistemology, and a decentralized intellectual ecosystem—that gave it exactly the room it needed to take root.

And yeah, some of this will be familiar. But I think there are connections worth drawing that we don’t talk about enough—especially when we trace how everyday American habits of mind shaped epistemology itself.

The Culture That Grew Pragmatism

1. Protestant Roots and Epistemic Fallibilism

Let’s start with something we all sort of know, but maybe haven’t unpacked fully: the influence of American Protestantism—especially its emphasis on individual interpretation and distrust of centralized religious authority.

You can trace a clear line between the Protestant Reformation’s decentralization of truth and the pragmatist commitment to fallibilism and experiential inquiry.

Think about it: for many American Protestants (especially in the Calvinist and later Evangelical traditions), truth wasn’t something handed down from a church hierarchy. It was discovered, tested, wrestled with—often individually.

That maps surprisingly well onto Charles Sanders Peirce’s view that truth is what a community of inquirers might eventually converge on, through long-term testing and correction.

It’s truth as a regulative ideal, not a divine decree. Peirce didn’t draw that connection explicitly, but the cultural atmosphere he breathed—steeped in a Protestant ethic of personal responsibility and inquiry—certainly set the stage.

And we can’t ignore William James here. His psychological and religious writings (especially in The Varieties of Religious Experience) clearly respect subjective spiritual insight—not as mystical truth, but as legitimate data for philosophical reflection. That tension between the personal and the empirical is distinctively American.

2. Life on the Frontier and Adaptive Thinking

The American frontier wasn’t just a physical space—it was an epistemic laboratory. Out on the edge of “civilization,” you couldn’t rely on inherited systems or abstract theory—you had to solve problems with what was in front of you.

That’s exactly the kind of mindset pragmatism valorizes: trial, error, adjustment, repeat. The idea that belief is a habit of action (Peirce), or that truth is what works in the long run (James), or that inquiry is a form of problem-solving (Dewey)—all of these grow organically from a culture where survival literally depended on practical adaptation.

Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis” gets a bad rap for its overreach, but there’s something undeniably useful in its claim that the frontier forged a new kind of American character—self-reliant, experimental, suspicious of authority, and always improvising. That’s not just sociology. It’s epistemology by necessity.

And Dewey, more than anyone, internalized that ethos. His educational and democratic theories aren’t just normative; they’re practical responses to a culture that values learning-by-doing over learning-by-receiving.

3. Decentralized Institutions and Intellectual Play

Finally, and maybe most importantly, we’ve got to talk about America’s institutional structure—because it wasn’t just the frontier that made pragmatism possible. It was the freedom to think weird thoughts in the open.

Unlike the tight, centralized academies of Europe (where German idealism, for example, had institutional gatekeeping), 19th-century America had a kind of chaotic intellectual democracy.

You had Harvard (where Peirce and James operated), the University of Chicago (Dewey’s lab), and a swarm of clubs, journals, and networks that let thinkers jump between psychology, philosophy, education, and politics without needing a passport.

Take The Metaphysical Club—it wasn’t a formal academic society; it was a bunch of sharp minds (Peirce, James, Holmes Jr., et al.) arguing over real problems in an open-ended way. That kind of environment was a breeding ground for methodological pluralism.

If Peirce had been stuck in the Sorbonne, would we have gotten abduction?

Would James have dared to defend mystical experience in Oxford?

I doubt it. They thrived because America didn’t demand coherence—it demanded results.

In short: Pragmatism didn’t just happen in America; it’s soaked in the assumptions, anxieties, and adaptive strategies of American life.

Protestant experimentalism, frontier logic, and decentralized institutions weren’t just historical contexts—they were living metaphors that pragmatism turned into method.

And once you start seeing that, it’s hard to unsee.

How American Life and Pragmatist Ideas Mirror Each Other

So now that we’ve looked at the cultural conditions that enabled pragmatism to emerge, let’s flip the lens: how does pragmatism reflect deeper structures of American life—not just historically, but in its enduring forms of thought?

If you’re like me, you’ve probably noticed that pragmatism doesn’t just describe a way of thinking—it actually mirrors some of the core habits of the American mind. I’m not talking about clichés like “Americans are practical” or “we love innovation.” I mean something deeper: the way our institutions, beliefs, and cultural reflexes work themselves out over time.

Here’s a closer look at some of those deep resonances.

1. Epistemic Modesty and Anti-Aristocratic Thinking

Pragmatism’s suspicion of final truths? That didn’t come from nowhere. The idea that no one gets the last word on reality—that even our most cherished beliefs are provisional—isn’t just Peirce’s scientific humility. It’s deeply democratic in tone.

This is a country built on a distrust of aristocracies, whether political, religious, or intellectual. We prize everyday reasoning, not just elite abstraction. When James says, “The true is the name of whatever proves itself to be good in the way of belief,” he’s not dumbing philosophy down—he’s extending epistemic rights to everyone. And that feels fundamentally American.

You can see this anti-elitism everywhere—from Emerson’s self-reliance to Whitman’s poetic democracy. Pragmatism picked up the thread and said: truth doesn’t need a throne. It needs consequences that matter to real people.

2. Experimentalism and Economic Innovation

Let’s not pretend the American economy didn’t play a role in shaping philosophical instincts. A culture of markets, invention, and constant reinvention teaches people not to ask “Is this true in the abstract?” but “Does it work?”

Sound familiar?

James’s willingness to entertain plural, even conflicting truths makes sense in a world of constant commercial flux. Dewey’s belief that we think in order to change our environment fits a culture of entrepreneurial trial-and-error. Even Peirce’s logic of abduction—”guessing right” as a method—is a kind of intellectual risk-taking that maps perfectly onto capitalist dynamism.

In short: pragmatism naturalized innovation as a way of knowing, not just a way of working.

3. Pluralism and the National Patchwork

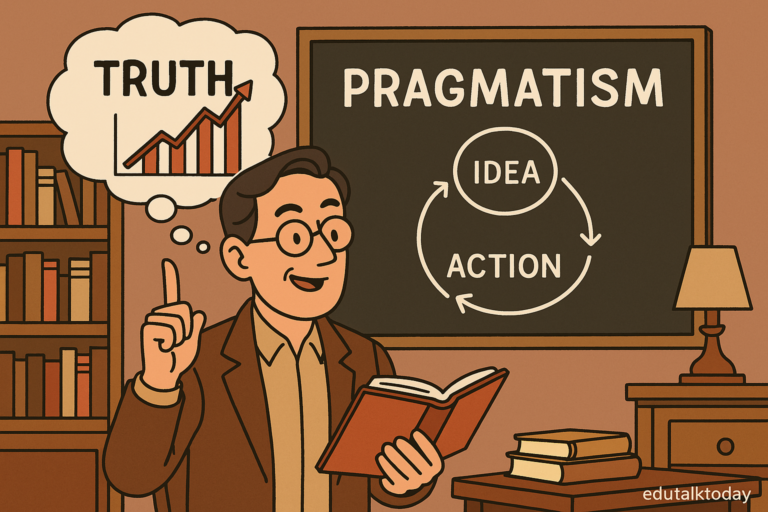

We can’t talk about pragmatism without acknowledging how pluralistic it is at its core. James loved the phrase “a pluralistic universe,” and that’s more than metaphysics—it’s sociology.

The U.S. was (and is) a cultural mashup: different languages, religions, values, and histories overlapping and competing. That’s not a bug—it’s the system. So it’s no wonder James and Dewey rejected any final unifying truth. They were building a philosophy for a culture that didn’t believe in single answers.

Instead of seeking unity, they built tools for managing difference. Truth, for James, is “made in the course of experience.” For Dewey, democracy isn’t just a political form—it’s a method of problem-solving among diverse actors. That pluralism isn’t just tolerated; it’s essential.

4. Meliorism and the American Belief in Progress

Here’s one I think we’ve all internalized: meliorism—the idea that the world can be made better through effort—is central to pragmatism and to American self-understanding.

Dewey, especially, takes this seriously. For him, democracy isn’t a system to defend—it’s an experiment to improve. Inquiry is never about arriving at certainty, but always about pushing toward better outcomes.

That fits the American ethos almost too perfectly. A land of reform movements, self-help, bootstrap narratives, and technological utopias—we’re practically allergic to finality. Pragmatism gave us a philosophical justification for perpetual improvement.

5. Utility as a Moral Compass

Finally, let’s talk ethics.

One thing that pragmatism refuses to do is separate moral reasoning from consequences. James and Dewey both argue that what’s good is what works well in lived experience—not just what aligns with some abstract principle.

Now, tie that to the Protestant work ethic and you get a powerful cultural alignment. In America, utility isn’t just pragmatic—it’s often moralized. Usefulness becomes a stand-in for virtue. James’s notion of the “will to believe” rests on this assumption: that a belief’s practical value can justify its acceptance.

That’s a bold claim—and one that only really makes sense in a culture that already believes work, effort, and results are ethical acts.

Pragmatism as a Feedback Loop Between Culture and Philosophy

At this point, I think we’ve got enough on the table to make a stronger claim: pragmatism isn’t just shaped by American culture—it shapes it right back.

Let me explain what I mean by that.

1. Pragmatism Reflects American Habits, But Also Codifies Them

We often treat pragmatism as a mirror: it reflects how Americans already think. But it’s also a manual—a way of codifying habits into theory. Take Dewey’s educational philosophy. It didn’t just respond to Progressive-era reforms; it also shaped how generations thought about schools, democracy, and public life.

Same with James’s psychology—it framed religious experience as data, not dogma. That shifted not just academic conversations but cultural norms around what counts as knowledge.

In this way, pragmatism became a kind of cultural self-consciousness. It showed America to itself—and in doing so, it helped steer the ship.

2. An Epistemology Built for a Democracy

There’s something beautifully recursive about the fact that pragmatism—a philosophy of continuous inquiry and correction—fits so neatly with democracy—a system of continuous deliberation and revision.

That’s not just a metaphor. Dewey explicitly saw democracy as an epistemic system: one where truth emerges not from authority, but from participation and experimentation. Every citizen becomes a mini-inquirer, testing beliefs against consequences.

In that sense, pragmatism wasn’t just compatible with American democracy—it was an instruction manual for how to think in one.

3. Why It Didn’t Happen in Europe (And Probably Couldn’t Have)

This one’s worth dwelling on: why didn’t pragmatism happen in France or Germany? They had science. They had political revolutions. But they also had deep commitments to system-building—from Descartes to Kant to Hegel—that made it hard to accept contingency and pluralism.

In contrast, American thinkers came of age in a system without an established church, without a rigid class structure, and without centuries-old philosophical institutions demanding orthodoxy. That intellectual looseness—combined with real institutional pluralism—meant you could get away with saying truth is a process, or that religious belief can be justified by its fruits.

In Europe, those would have been heresies. In America, they became bestsellers.

4. Cultural Resonance Across Time

One thing I’d argue is that pragmatism continues to resonate precisely because it evolves with American culture. In the 20th century, you see echoes in everything from legal realism (hello, Holmes and Cardozo) to public policy (evidence-based governance) to Silicon Valley’s love affair with iteration and feedback loops.

Even contemporary moral debates—around identity, rights, and experience—often play out in pragmatist terms: what works, what empowers, what fosters better outcomes.

Pragmatism is still quietly running in the background, shaping how we argue, decide, and act.

Finally…

So what do we do with all this?

Here’s my take: pragmatism isn’t just a product of American culture—it’s its philosophical double. It took the raw material of daily life—risk, diversity, experimentation, fallibility—and turned it into a theory of truth, knowledge, and ethics.

And here’s the kicker: we don’t always see it because we’re still living it. Pragmatism wasn’t a temporary philosophical moment. It’s a self-renewing loop between how Americans think and how they want to think.

If anything, it’s more relevant now than ever.