How Overlapping Disadvantages Shape Social Isolation and Unequal Social Networks

A new study published in Science Advances takes a deep dive into how identity, structural patterns, and social behavior combine to shape who ends up well-connected—and who ends up pushed to the edges of a network. The research looks at something many people sense intuitively but rarely understand in detail: being part of more than one marginalized group can create disadvantages in forming friendships that are far greater than a simple sum of the parts. The study shows how these disadvantages can amplify, creating compounding inequality in access to social connections, support, and opportunities.

The work comes from the Complexity Science Hub (CSH) in collaboration with TU Graz. The researchers—Samuel Martin-Gutierrez, Fariba Karimi, and Mauritz N. Cartier van Dissel—wanted to examine how gender, ethnicity, and other identity traits interact to influence social ties. Instead of assessing each trait one at a time, they developed a model capturing multiple overlapping identities, then tested it with data from about 40,000 U.S. high-school students from the 1994/95 school year.

Below is a straightforward walkthrough of every major finding and detail from the study, followed by additional context explaining why this research matters and how it fits into what we know about social networks and inequality.

Understanding the Purpose of the Study

The researchers were trying to answer a deceptively simple question: Why do some groups consistently have more social connections while others struggle to build or maintain them?

To get a complete picture, they looked beyond individual choices. Instead, they focused on structural patterns, group preferences, and the way identity traits overlap. They specifically wanted to see whether disadvantages combine in predictable, additive ways—or whether they create nonlinear effects that could not be guessed by looking at single identity traits alone.

They found strong evidence that intersectional disadvantages—for example, belonging to a minority ethnic group and being female—produce outcomes that differ sharply from what you’d expect if you analyzed each trait independently.

The Role of Homophily in Social Networks

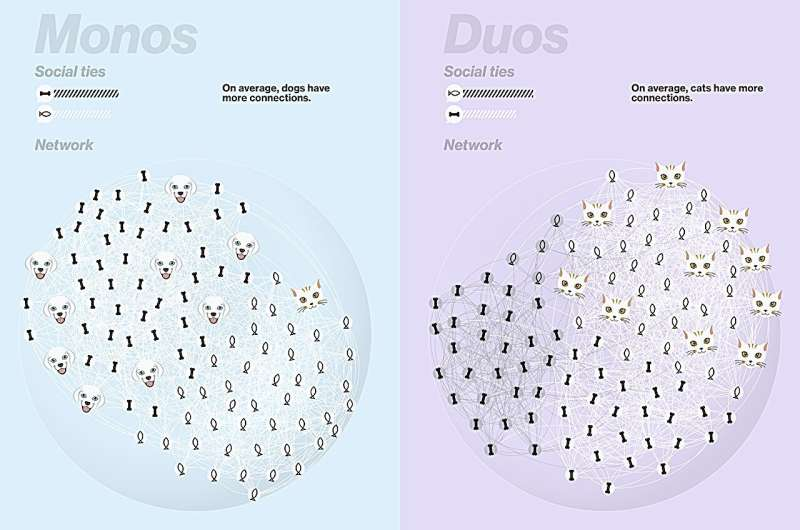

A major force shaping social networks is homophily, which is simply the tendency for people to connect with others who are similar to them. This applies across gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, grade level, and more.

While homophily can feel natural on an individual level (“people like people who are like them”), it produces large-scale structural effects:

- Majority groups form dense, well-connected clusters.

- They connect heavily among themselves and to the central parts of the network.

- Minority groups end up on the periphery, with fewer ties and less access to the well-connected core.

- People in these peripheral groups often connect mostly to others who are also poorly connected.

This double layer—fewer connections, and connections to less-connected people—makes it harder for marginalized groups to access opportunities such as mentorship, information, support, or professional pathways. The researchers refer to this phenomenon as structural invisibility, because these groups become almost invisible within the central flow of social information.

Why Overlapping Identities Matter

The study focuses heavily on intersectionality, a concept that describes how multiple marginalized identities can combine to produce unique disadvantages.

The researchers wanted to see whether social-tie disadvantages simply stack up—like adding one disadvantage to another—or whether something more complex happens. They found that overlapping traits can produce amplified, nonlinear, and sometimes unexpected effects.

For example:

- Girls generally had more friendship nominations than boys.

- But Black girls were a clear exception: they had among the fewest social connections.

- Their tie disadvantage was stronger than what you would predict based on gender alone or ethnicity alone.

Similarly:

- Asian boys also had very few ties.

- White girls had the most social ties of any group.

- White boys were also above average due to their majority status.

These patterns show clearly that identity traits don’t operate independently. They intersect in ways that reshape outcomes.

Unexpected “Emergent” Advantages

One of the more surprising findings is that some groups experienced unexpected advantages based on context. In certain grade levels, Black boys were actually better connected than several other groups—despite being disadvantaged along both ethnicity and gender lines.

The researchers call this phenomenon emergent intersectionality. It highlights that:

- Group size,

- Connection preferences,

- Demographic composition,

- And correlations between traits

can produce new patterns that do not follow simple additive logic.

This is an important reminder that structural systems can create outcomes that are counterintuitive unless you examine all interacting factors.

Using Real-World Data to Test the Model

To evaluate their model, the research team used well-known data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Each student in the dataset listed their self-identified friends and demographic information—gender, ethnicity, grade level, and more.

Key details:

- Sample size: ~40,000 students

- Timeframe: 1994/95

- Setting: U.S. high schools

- Data included both outgoing and incoming friendship nominations

- The model achieved about 92% accuracy when predicting friendship patterns

This high level of accuracy suggests the network model captures important underlying social forces.

Why These Findings Matter

The study’s results give us a clearer picture of how social disadvantages can emerge from the structure of networks, not just from personal choices or prejudices. Social ties are a form of social capital, meaning they influence access to:

- Opportunities

- Information

- Support systems

- Future prospects

If certain groups consistently have fewer ties—and weaker ones—their long-term opportunities can be limited.

The researchers believe that understanding intersectional dynamics in social networks can help:

- Build more inclusive school environments

- Identify groups that may need more support in connecting

- Improve social-platform design

- Inform policy that addresses structural inequities early

- Reveal hidden disadvantages that single-trait analyses miss

The study also reinforces the idea that no group can be fully understood by looking at one identity trait at a time.

Extra Context: Why Network Position Matters in Real Life

To help readers understand the broader significance, here are some foundational ideas from network science that relate to the study’s findings.

Centrality and Opportunities

People closer to the “center” of a network tend to receive:

- More information

- More support

- More recommendations

- More visibility

- More chances to form new ties

Meanwhile, peripheral groups—even if skilled or motivated—may be overlooked simply because they sit at the edges.

Weak Ties vs. Strong Ties

Research shows that weak ties (acquaintances) often play a major role in job opportunities and social mobility. Marginalized groups with fewer weak ties are structurally disadvantaged even if they have strong connections within their own group.

Correlated Attributes

Traits like ethnicity and socioeconomic status often correlate, meaning inequalities along one dimension can reinforce inequalities along another. This makes intersectionality particularly important to study.

Why This Study Pushes the Field Forward

This research is valuable because:

- It provides a mathematical framework for understanding intersectional tie inequalities.

- It bridges sociology, network science, and fairness research.

- It offers closed-form predictions, not just simulations.

- It shows how multiple identity traits interact in realistic networks.

- It exposes patterns that previous one-trait-at-a-time studies could not detect.

Overall, it paints a detailed picture of how identity, structure, and behavior intertwine to shape social possibilities.

Research Paper:

Intersectional Inequalities in Social Ties – Science Advances